19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution:

“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.”

by Amy Wolf

At a time when Americans are voicing their opinions at the ballot box and in other ways, Vanderbilt University is joining people across Tennessee and the nation in commemorating the centennial of the long-fought battle to secure a woman’s constitutional right to vote. Aug. 26 marks the 100th anniversary of the adoption of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

It took more than 70 years to ratify the 19th Amendment, and Tennessee played a critical role in its passage. Though most Southern states were adamantly opposed to the amendment, on Aug. 18, 1920, the Tennessee General Assembly passed the ratification resolution for the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, crossing the threshold of the three-fourths of states needed.

It took more than 70 years to ratify the 19th Amendment, and Tennessee played a critical role in its passage. Though most Southern states were adamantly opposed to the amendment, on Aug. 18, 1920, the Tennessee General Assembly passed the ratification resolution for the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, crossing the threshold of the three-fourths of states needed.

But even that crucial vote passed by a thread. Tennessee state legislators were in a 48-48 tie. The state’s decision came down to 23-year-old Rep. Harry T. Burn, a Republican from McMinn County, to cast the deciding vote. Although Burn himself opposed the amendment, his mother convinced him to “be a good boy” and vote for it, thus turning the tide for the entire country.

With 36 states passing the amendment, women officially gained the right to vote when it took effect on Aug. 26, 1920.

Vanderbilt connection

Even before the final vote, a Vanderbilt alumnus played a crucial role in keeping the amendment from being tabled in the Tennessee Legislature. Despite heavy pressure, Rep. Banks Turner, a 1910 graduate and freshman lawmaker from Gibson County, voted three times to prevent the resolution from being tabled, which would have effectively killed it.

The legal fight was nicknamed the “War of the Roses” because supporters of suffrage wore yellow roses and anti-suffragists wore red roses, allowing for unofficial tallies. Both Turner and Burn pinned red roses to their lapels, but each switched sides in support of ratification during roll call.

No magical transformation

While the law changed, it took longer for societal norms to catch up. Rory Dicker, author of A History of U.S. Feminisms and director of the Margaret Cuninggim Women’s Center at Vanderbilt, said gaining the legal right to vote did not magically transform the massive societal inequities between men and women or among women of different socioeconomic and racial backgrounds.

“Mainstream society did not think women needed the vote because men had been speaking for women for quite some time,” said Dicker, who is also a senior lecturer at Vanderbilt.

“White, middle-class women in the 19th century were relegated to the domestic sphere. And when they married, there was something called coverture under English common law, which is an idea that women became civilly ‘hidden.’ They couldn’t keep their wages if they worked outside the home; they couldn’t inherit property; they couldn’t sue or enter into contracts; and they couldn’t vote,” Dicker explained.

Dicker said that by the turn of the century, white women’s status had begun to change as state laws began to recognize property owned by married women. In addition, some women were starting to gain an education and to work outside the home. But bitter social and racial disparities still remained.

The 19th Amendment did not clear roadblocks for all women. While Black women were active in women’s suffrage efforts across the nation, white supremacy within the movement and racist voting laws passed after ratification—including literacy tests, poll taxes and other discriminatory practices—disenfranchised many Black voters for decades, until Civil Rights protests helped push the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

“During the suffrage movement, there were white Southern women who campaigned for suffrage who later, because of their racism, reneged on their beliefs in women’s rights and joined with people who were actively campaigning against suffrage,” Dicker said.

Nashvillian Frankie Seay Pierce was one of several prominent African American Tennesseans lobbying for the right to vote, and she was the only Black citizen invited to address the May 1920 suffrage convention in the Tennessee Capitol building. When asked why she was fighting for the right to vote, she answered, “We want the same moral uplift for the community that is sought by white women voters. We want recognition in all forms of this government. We want a state vocational school and a child welfare department and more room in state schools. We ask for one thing—a square deal.“

The Hon. Claudia Bonnyman, JD’74, whose great-grandfather was the governor of Tennessee at the time of the 19th Amendment’s ratification and lobbied for its passage, recently spoke about the history of the Black suffragist movement in Nashville. She said Pierce had gained credibility with the white suffragists based on her fundraising for the Red Cross and YWCA during World War I as well as her advocacy for improved health care for American soldiers.

Pierce is one of the five Tennessee suffragists depicted in the Woman Suffrage Monument at Nashville’s Centennial Park.

It took an additional 60 years from the time of ratification for all of the states within the U.S. to pass the 19th Amendment. Mississippi was the last to do so in 1984. And though the 19th Amendment was certainly a step forward in the fight for women’s rights, the legal push continues.

In 1923, some of the same women who fought for suffrage and wrote the legislation around the 19th Amendment crafted the Equal Rights Amendment.

“And of course, we have not had that ratified these many, many years later,” Dicker said. In January 2020, Virginia became just the 38th state to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment.

Issues like pay equity, parental leave and gender-based violence have inspired new generations to join the women’s rights movement. An updated report on the gender pay gap from the Center for American Progress shows white women make 79 cents on the dollar compared to white men. Black women earn 62 cents and Latinas earn just 54 cents for each dollar earned by a white man.

Vanderbilt’s fight for women’s equity

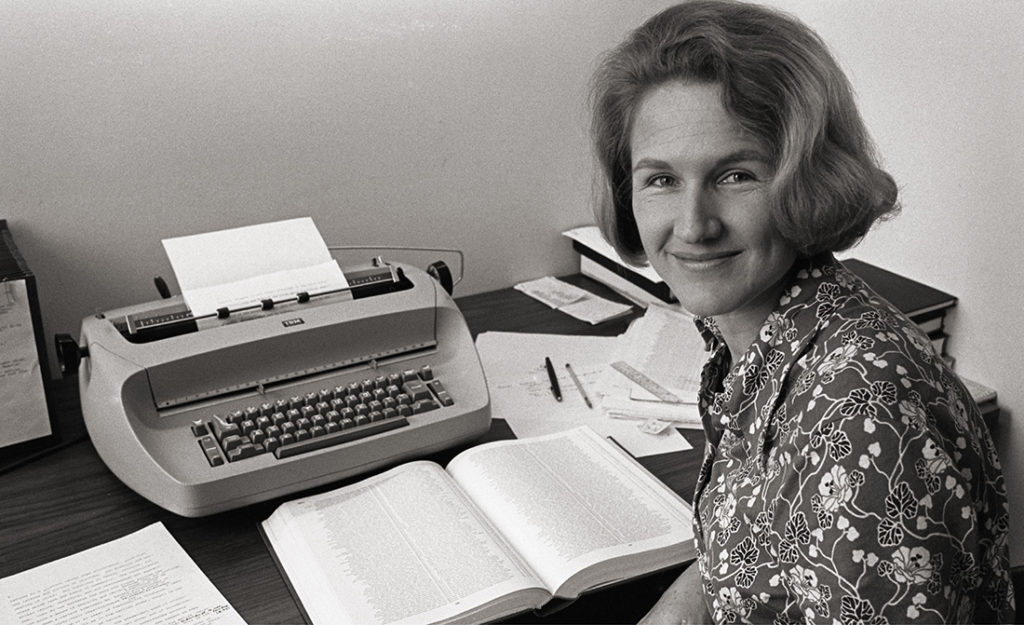

Susan Ford Wiltshire, professor of classical studies, emerita, led a charge at Vanderbilt for women’s equity among faculty in the early 1980s after a highly qualified female professor was denied tenure despite having a majority of votes from her department.

“Like the suffragists, we learned the power of organizing over just agonizing,” Wiltshire said. “And we learned the power of working on a cause that would benefit future generations. But even 40 years ago, it was thought of as threatening for women to organize.”

Wiltshire said just as the suffragists inspired her and fellow women at Vanderbilt to launch Women for Equity at Vanderbilt (WEAV), current human rights protestors are also learning from history.

“To be activists on the issues of racism, women’s issues, full acceptance of LGBTQI people—all of these require people to be inspired to push for active change and answer the call, and that is a powerful thing,” she said.

Timeline of women’s suffrage

- 1848 – The first women’s rights convention occurs in Seneca Falls, New York, where a resolution in favor of suffrage narrowly passes

- 1919 – Congress approves the 19th Amendment

- 1920 – After gaining support from 3/4 of states, the 19th Amendment is ratified into law

- 1965 – Voting Rights Act strips racist practices that limited voting rights

- 1984 – Last U.S. state (Mississippi) ratifies the 19th Amendment