The ancient Egyptians were the first to mention the brain in writing—preserved on a 2,700-year-old papyrus that details the symptoms of head injuries—but the importance of the organ escaped them. They believed it was the heart, not the head, that controlled human thought and emotion.

Today our knowledge of the brain has far eclipsed what our forebears knew only a few generations ago, never mind 27 centuries. The burgeoning field of neuroscience has led to an almost unprecedented burst of scientific research, reshaping disciplines from biochemistry and personalized medicine to law, psychology and the arts. Meanwhile, newer imaging technologies, like functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), have offered revolutionary ways to view brain activity in real time.

As a result of these and other breakthroughs, neuroscience has permeated our lives as never before. Yet, as researchers learn more about the brain, the more its mysteries grow in ways that don’t lend themselves easily to a single discipline. Scientists have been unable to disentangle, for example, genetics and anatomy from human experience and emotion.

What is required instead is a closely collaborative, multidisciplinary approach to understanding the brain. For more than 20 years, Vanderbilt has done just that, leveraging its culture of collaboration to emerge as a leader in neuroscience research and education. Now, as our knowledge of neuro-everything continues to grow—aided by emerging technologies like artificial intelligence and data science—the university has reaffirmed its commitment to this important space.

“Vanderbilt is on the leading edge of neuroscience discovery in research, education and training,” says Provost and Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs Susan R. Wente. “You can see it in the breadth of our neuroscientists’ work, from their innovative use of scanning technology to better understand the brain’s many functions, to the advances they’ve made in pharmacology and biochemistry as they pursue treatments for some of the world’s most vexing neurological disorders.

“More important, though, you see it in how these scientists work together across their diverse fields, lending expertise and support to each other’s efforts, as they further our knowledge of the brain. Vanderbilt’s success in neuroscience ultimately depends on this teamwork.”

At the center of this work is the Vanderbilt Brain Institute, a trans-institutional entity that oversees and facilitates neuroscience-related endeavors across the university and in partnership with Vanderbilt University Medical Center. The VBI recently marked its 20th anniversary, a span that has seen the institute’s wide-ranging missions—including administering the university’s Neuroscience Graduate Program, as well as postdoctoral training and community outreach—steadily coalesce under a single umbrella.

Of those 20 years, the past two in particular have been among the most transformative for the VBI, as Vanderbilt has allocated new resources toward its continued expansion, including a reimagined physical home on campus. The university also has raised the institute’s visibility by bringing in Lisa Monteggia, an esteemed researcher and educator from UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, to lead it.

Hired in September 2018 as the VBI’s Barlow Family Director following a nationwide search, Monteggia has begun implementing a forward-looking plan for the institute, making strategic decisions and investments that not only expand and enhance Vanderbilt’s neuroscience community and its collaborative spaces on campus but also harness the creative, cross-disciplinary synergy that naturally results from those efforts.

“The idea is to take advantage of our strengths, including the incredible collegiality we have as a smaller university, as we continue to grow and build,” says Monteggia, who is also a professor of pharmacology. “We’re hiring new faculty and also exploring different areas of collaboration, like connecting the arts with psychiatry, for example, or the biological sciences with education and engineering. It’s really about building bridges that further our understanding of the brain.”

GROWING REPUTATION

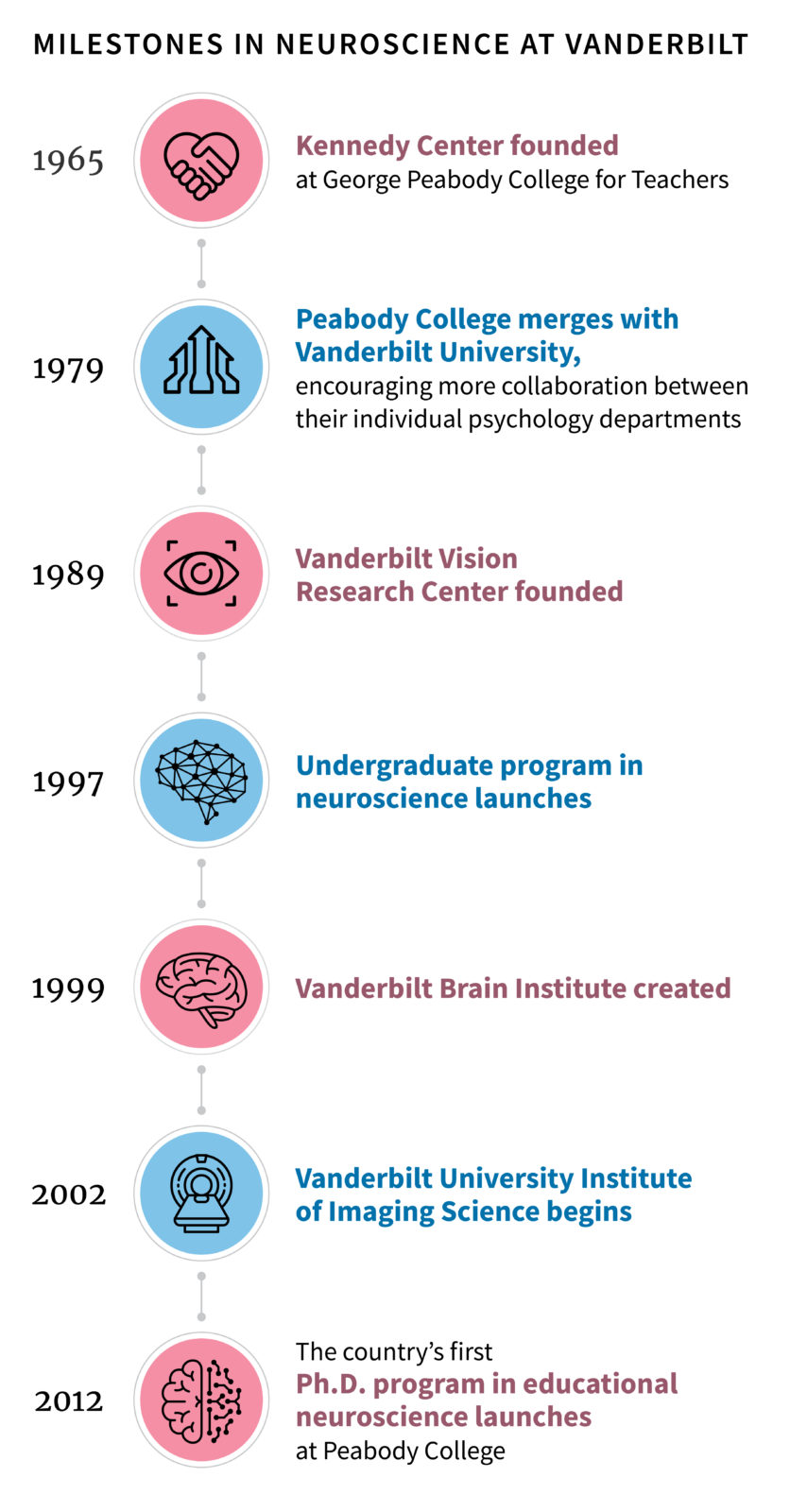

Vanderbilt’s roots in neuroscience stretch back several decades before the launch of the VBI. For example, in the 1950s and ’60s, developmental psychologist Susan Gray’s pioneering work helped George Peabody College for Teachers develop a national reputation for research on intellectual and developmental disabilities, leading to the launch in 1965 of what is today known as the Vanderbilt Kennedy Center for Research on Human Development. The VKC works to improve the lives of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities through research, education and advocacy.

By the 1970s there would be other key faculty additions, including the late psychology professor Oakley Ray, who introduced the academic focus of neuropharmacology, and Jon Kaas, the Gertrude Conaway Vanderbilt Distinguished Professor of Social and Natural Sciences.

Since his arrival at Vanderbilt in 1973, Kaas has seen the neuroscience landscape at the university grow significantly, thanks in part to his own numerous contributions to the field, including illuminating how sensory information is distributed and integrated in the brain. But Kaas is also quick to note the impact of other faculty who have brought neuroscience to the forefront at the university.

Among them was the late Vivien Casagrande, professor of cell and developmental biology, psychology, and ophthalmology and visual sciences, whom Kaas helped convince to come to Vanderbilt. Arriving on campus in 1975, she spent the next several decades expanding our knowledge of how the visual thalamus and cortex interact to construct our perceptual world.

Says Kaas, “She was really the first faculty member trained as a neuroscientist to be hired at Vanderbilt.”

Casagrande and Kaas were founding members of the Vanderbilt Vision Research Center (VVRC), launched in 1989 to enhance research and training in visual neuroscience in the Department of Psychology, Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, and others at the Medical Center. The concentration in vision science attracted other key faculty, including Randolph Blake, MA’69, PhD’72, Centennial Professor of Psychology and professor of ophthalmology and visual science, in 1988, and Jeffrey Schall, E. Bronson Ingram Professor of Neuroscience and professor of psychology and ophthalmology and visual sciences, in 1989.

Like Kaas, both are among the two dozen or so neuroscientists at Vanderbilt who have been elected fellows of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Blake studies human visual perception, including binocular vision, motion perception and perceptual organization, while Schall investigates the neural and computational mechanisms of decision making.

Kaas also points to the hiring in 1991 of Ford Ebner, professor of psychology, emeritus, who has helped further our understanding of the brain’s plasticity (i.e., its ability to be molded and shaped by experiences), and his wife, Leslie Smith, principal senior lecturer of psychology. Vanderbilt’s first neuroscience Ph.D., in fact, was awarded to one of Ebner’s students. Kaas credits Smith, who previously had taught at Brown University, for elevating neuroscience education at Vanderbilt, particularly on the undergraduate side.

“Leslie introduced the idea of a neuroscience major, and that really set things in motion,” says Kaas of what is today the Interdisciplinary Program in Neuroscience for Undergraduates. “The undergraduate program has fed into our graduate program and everything else that has come since.”

Started in 1997, the undergraduate program, which is now administered by the VBI, is today the third largest major in the College of Arts and Science, with 355 students. Those who major in neuroscience typically go on to some of the country’s most competitive medical schools or graduate programs in neuroscience, biology or psychology.

Meanwhile, as the undergraduate program was getting off the ground, Elaine Sanders-Bush, PhD’67, professor of pharmacology, emerita, led the launch of the Neuroscience Graduate Program and would go on to serve as its director until 2008. During that decade the program grew to more than 60 graduate students. Since then, it has evolved into the largest graduate program on campus with 109 training faculty and 82 current students.

The development of undergraduate and graduate programs in neuroscience was paralleled by the establishment of institutional research centers. The Center for Molecular Neuroscience, founded under direction of Randy Blakely in the School of Medicine, organized resources and motivated faculty hiring to investigate the cells and molecules of the brain. The complementary Center for Integrative and Cognitive Neuroscience, launched in 2000 under the direction of Jeffrey Schall, organized resources and motivated faculty hiring to investigate the circuits and functions of the brain.

The Vanderbilt Brain Institute was established to administer the graduate program and facilitate synergy of these centers with the VKC, VVRC and the involved departments. Sanders-Bush, whose research has contributed to our understanding of serotonin and its receptors, also served as the VBI’s first director.

Coinciding with the launch of the VBI in 1999 were a couple of new faculty additions—Isabel Gauthier, David K. Wilson Professor of Psychology, and René Marois, professor and chair of the Department of Psychology and professor of radiology and radiological sciences—who would prove to have an important impact at Vanderbilt. Both had earned their Ph.D.’s at Yale University and—along with Randolph Blake and Ford Ebner—were early promoters of fMRI, Gauthier using it to explore visual object recognition and Marois to study the neural bases of attention and information processing.

Their move to Vanderbilt would help prompt their Yale mentor John Gore to follow them, bringing more than a dozen colleagues to establish the Vanderbilt University Institute of Imaging Science in 2002. Gore, the University Professor of Radiology and Radiological Sciences and holder of the Hertha Ramsey Cress Chair in Medicine, is known internationally for his pioneering work in biomedical imaging techniques.

During the past two decades, the university has become a magnet for other prominent neuroscientists, with a number of influential centers focused on brain research taking root, including the Warren Center for Neuroscience Drug Discovery and the Center for Cognitive Medicine.

RARE OPPORTUNITY

As the VBI continued to evolve into a more cohesive framework, it got a champion in the form of Mark Wallace, an expert on multisensory processing who became director in 2008. Currently the dean of Vanderbilt’s Graduate School and holder of the Louise B. McGavock Chair, Wallace led the VBI to national prominence, spurring research while also bolstering its education initiatives, including helping launch the country’s first Ph.D. program in educational neuroscience at Peabody College in 2012.

“We’re hiring new faculty and also exploring different areas of collaboration, like connecting the arts with psychiatry, for example, or the biological sciences with education and engineering. It’s really about building bridges that further our understanding of the brain.”

Wallace’s decision to step down from the VBI’s directorship and become dean in 2016 provided an opportunity for Vanderbilt to refocus its approach to neuroscience. To aid in the search for Wallace’s successor, David Barlow, the chairman and CEO of Psy Therapeutics, a Boston-based startup developing treatments for anxiety, depression and dementia, provided the gift to endow the Barlow Family Directorship, ensuring that the VBI would be able to recruit the best talent to that position in both the near and long term. (Among the members of Psy Therapeutics’ scientific advisory board is Dr. Sachin Patel, the James G. Blakemore Professor of Psychiatry, who studies cannabinoid neurobiology at Vanderbilt.)

“While the VBI already had a solid foundation, there was a clear opportunity to grow the mission and expand,” says Barlow, who got involved with Vanderbilt, including service on the Technology Transfer Advisory Committee, after his daughter Kelly Barlow, BA’12, was a student. “It was exciting to think about leveraging the ethos on campus and turning the institute into a hub that further facilitates interdisciplinary collaboration.

“The VBI has a huge future ahead of it under Lisa’s leadership.”

Coupled with the endowed directorship was a decision to move the VBI under the Office of the Provost. Aside from raising the institute’s stature and visibility on campus, the move afforded a more direct line of communication with Wente, herself a pathbreaking scientist who was instrumental in convincing Monteggia to join Vanderbilt’s faculty.

“It’s unusual to have a provost with such a strong scientific background. She understands the importance of investing in the best science and has been incredibly supportive,” Monteggia says. “As a colleague reminded me before I took the job, there are very few opportunities like this that come along in any given professional career. The opportunity to lead and serve the VBI was simply too great to pass up.”

COMMON GROUND

Monteggia’s research focuses primarily on two areas. One is antidepressants and how they work, with the particular goal of developing more effective treatments for depressed individuals who have exhibited resistance to conventional drugs and are therefore more prone to suicide. The other area is the underlying causes of Rett syndrome, an autism spectrum disorder. While antidepressants and Rett syndrome may seem like two very distinct paths of inquiry, they overlap in one critical sense.

“Certain neurodegenerative disorders, like Alzheimer’s, are characterized by loss of particular cells,” Monteggia says. “But there are other disorders like depression and autism that display no gross morphological anatomical changes in the brain. That suggests they are caused instead by functional changes at the level of how the neurons communicate. So we work backwards and look at a number of genes that are linked to these processes.”

Finding common ground to explore these and other neuroscience questions is a key part of Monteggia’s vision for the VBI, and for her that begins quite literally with the physical location itself. Upon accepting the directorship, she worked with Wente to establish a better-defined home for the institute on the seventh and eighth floors of Medical Research Building III. The space now includes expanded offices and conference rooms, additional seating lounges, and a refurbished balcony area to host visiting luminaries in the field and other gatherings—all designed with the aim of fostering collaboration.

“We’re currently 109 faculty members split across 24 different departments,” Monteggia says of the VBI. “And neuroscience is also the largest graduate program on campus. So the idea is to have a place for them all to come. It’s about bringing people together to talk about ideas, discuss projects, and just get to know each other.”

As expansive as the VBI already is, Monteggia wants to continue growing the institute by working with deans on campus, particularly those at the College of Arts and Science, Peabody College, the School of Engineering, and the School of Medicine’s Basic Sciences, to make strategic faculty hires. And as part of that process and the VBI’s other initiatives, she is ever mindful of the role that diversity and inclusion should play in that growth.

“I’m a firm believer that the more diversity we have, the better we’ll be able to approach a problem and see it from different angles,” she says.

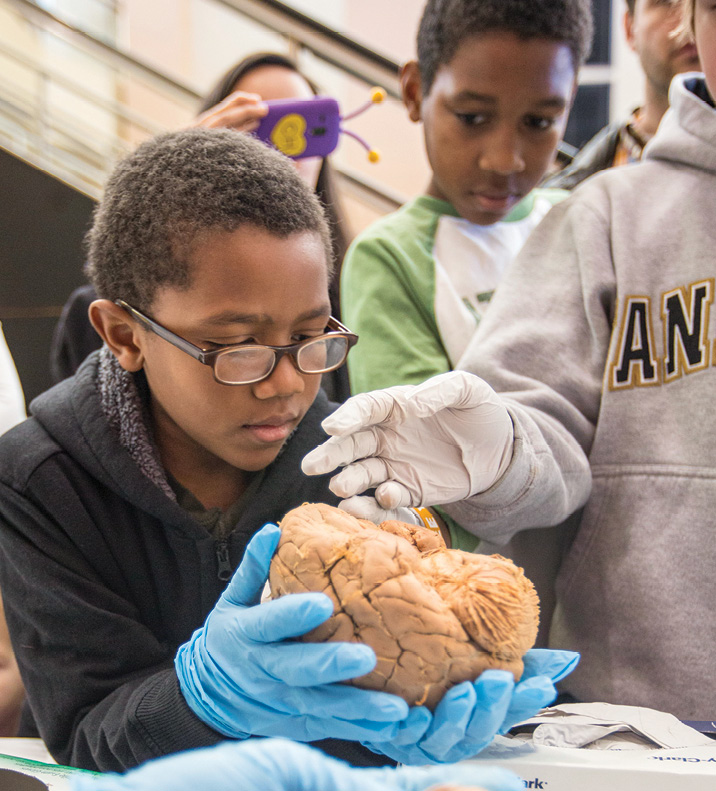

Monteggia also recognizes that the VBI’s role doesn’t stop at the edge of campus. Its work can and should reverberate well beyond the classrooms and labs and into the wider community of Middle Tennessee, she says. This includes, among other things, having Vanderbilt students speak at local schools on neuroscience-related topics, collaborating with the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute on programming related to the aging brain, and organizing free public events and activities for Brain Awareness Month each March.

Ultimately, the VBI’s work is part of a long continuum of efforts, now many centuries old, to demystify the brain and unwind its tangled secrets for the greater benefit of society. This endeavor has pushed our knowledge of neuroscience further than many ever could have predicted only a few generations ago, but there remains so much more we do not understand about the brain. And if the past is any indication, the more deeply we peer inside its folds, the more questions there likely will be.

“As we’re going about this transformation, there’s always an eye towards the future. I do have a vision for where we’re going, but I’m trying to do it in a way that brings the most people together as possible,” Monteggia says. “That’s the only way we’ll be able to answer these big questions facing science and society as a whole.”

Seth Robertson is executive editor of Vanderbilt Magazine.