By Ryan Underwood, BA’96

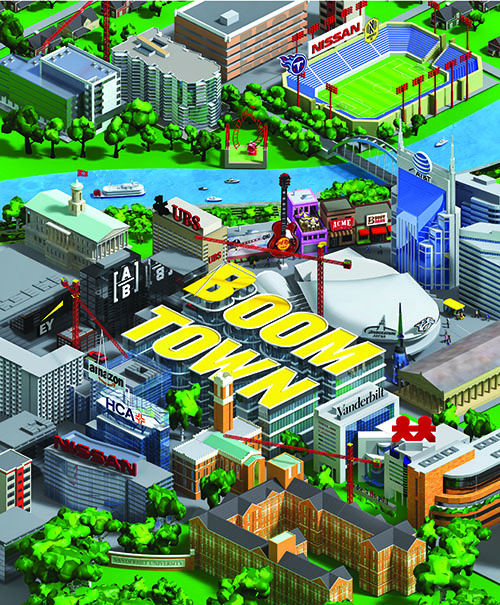

“Portland knows the feeling. Austin had it once, too. So did Dallas. Even Las Vegas enjoyed a brief moment as the nation’s ‘it’ city. Now, it’s Nashville’s turn.”

Those words—less than 30 in all—opened a story that ran on page 11 of a Wednesday edition of The New York Times in 2013. Despite the modest placement, that “it city” designation sparked a tourism and economic development turbocharge in Nashville that continues to this day.

By 2018, as if to seal the city’s blazingly ascendant reputation, tech giant Amazon and global investment firm AllianceBernstein announced they would move parts or all of their corporate headquarters to downtown. Around the same time, companies like Ernst & Young, Mitsubishi Motors, Asurion and startup SmileDirectClub all revealed major new investments in or relocations to the Nashville area.

Those latest corporate moves, in turn, seem to have generated yet another round of buzz for the city. In the past year alone, Nashville hosted the most-watched NFL Draft in the league’s history, played a starring role in Ken Burns’ acclaimed Country Music documentary series on PBS, had two of the city’s restaurants featured in Bon Appétit’s annual list of Best New Restaurants, and continued populating a variety of other best-of lists from media outlets around the world. Even devoted fans of the now-ended Nashville television show still pack the awkward sidewalks of Green Hills each weekend to catch a glimpse inside the famed Bluebird Café.

Nashville’s boom has become such a part of the city’s identity that there’s hardly a resident who can’t recite some version of the head-spinning statistic that Nashville’s population has grown on average by nearly 100 people per day each year for the past 10 years, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. The rapid pace continues, with city planners forecasting that the Nashville area will add another million residents by 2035.

To Chancellor Emeritus Nicholas S. Zeppos, Nashville’s rise as a vibrant cultural and economic center has always been assured—and is inseparably linked to Vanderbilt’s own achievements. “There’s an old joke,” Zeppos told a crowd of business and political leaders at Nashville’s Rotary Club in August 2018. “What’s the best economic plan? Build a major research university and wait 50 years.”

He explained that top universities like Vanderbilt don’t come along very often, and for cities that have one in their backyards, “it’s like the four-leaf clover.”

A new economic impact report released in January quantifies the university’s impact on the Nashville area. The study finds that Vanderbilt institutions—the largest private employers in the region, and second largest in the state—annually contribute $11.9 billion in economic activity and $4.2 billion in labor income and support.

Since 2010, Vanderbilt has awarded about 30,000 degrees, providing the region with a vast pipeline of talented graduates. And more of those former students seem to be staying in town. The undergraduate class of 2018, for example, chose Nashville as nearly the most popular destination—slightly edged out by New York—for those who accepted full-time jobs. For those continuing on to graduate or professional school, Vanderbilt was the most popular choice, followed by Columbia and Harvard.

“I think that Vanderbilt and Nashville share an innovative, creative spirit that attracts a broad range of students, entrepreneurs and professionals to the area from around the globe,” says Susan R. Wente, interim chancellor and provost. “From contributing to a highly skilled and educated workforce, to spurring new startups and discoveries, testing smart-city applications or hosting forums with internationally renowned artists, musicians and policymakers, Vanderbilt’s community offers significant engagement opportunities for the city. But, more so, it’s only through a dynamic partnership that Nashville and Vanderbilt will continue to have a sustained positive impact on each other’s growth and development.”

‘NASHVILLE BECAME COOL’

Shortly after Butch Spyridon, BA’78, returned to his alma mater’s hometown in 1991 to lead the Nashville Convention and Visitors Corp., he picked up a copy of the local alternative paper and his heart sank. “The Nashville Scene had just come out with its annual list of best restaurants, and Pizza Hut won best pizza and Red Lobster won for best seafood. And I just thought, ‘What have I done?’” Spyridon recalls, still palming his forehead in disbelief. “With all due respect to those restaurants, it’s not exactly something you can hang your hat on to promote an exciting destination.”

Fast forward 20 years, and a writer for Bon Appétit is telling the world about the fun he’s having on a tour of the “coolest, tastiest city in the South,” being led by Black Keys frontman Dan Auerbach and James Beard Award–winning chef Tandy Wilson.

That scene, as much as anything, captures Nashville’s transformation during the past two decades.

“If any of my classmates hadn’t been back to Nashville since they graduated, they’d die laughing,” Spyridon says, pointing out that there was little else for Vanderbilt students to do in his era other than enjoy cheap beer with the Budweiser mascot, “Budman,” in either the Towers Bar (yes, there was a bar in Towers) or at the Overcup Oak.

Today there are any number of celebrities, other than country music stars, who call Nashville home, including Nicole Kidman, Ted Danson, Justin Timberlake and supermodel Karen Elson. The area is also home to two massive music festivals each spring, the CMA Fest and the eclectic rock fest Bonnaroo.

The city boasts three major league sport franchises—including the Tennessee Titans and Nashville Predators—and, in an effort led by current Vanderbilt trustees John Ingram, MBA’86, and Mark Wilf, along with Emeritus Trustee Steve Turner, BA’69, and his son Jay Turner, BA’92, JD’99, one of the newest major league soccer franchises, Nashville SC, began playing in February.

Renowned chefs have flocked to Nashville as well, from such exclusive restaurants as Napa Valley’s Per Se and Copenhagen’s Noma. Nashville has even regained a nonstop flight to London—a route it had in the late 1980s and early ’90s but lost because of low demand.

In short, “Nashville became cool,” Spyridon says.

How?

First, it embarked on a marketing campaign in the early 2000s that embraced the creative spirit that originally earned Nashville its most recognizable nickname: Music City. It expanded beyond country music and became a hit with rock icons such as Jack White, and Def Jam Records co-founder Rick Rubin, who collaborated with Johnny Cash on the Grammy-winning American Recordings project.

Second, it intentionally clustered a slate of new attractions around downtown, including a 20,000-seat arena, an NFL stadium, the enormous Music City Center, a reimagined Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, the Schermerhorn Symphony Center, and the Frist Art Museum, among many other projects.

Third, it went out and generated some transformative national and international media exposure. In addition to recognition by The New York Times, GQ dubbed the city “Nowville,” Travel + Leisure in July named Nashville as one of the top 15 destinations in the world, and in November the Today show hosted its third-hour programming from Nashville, showcasing multiple sights around the city. Condé Nast Traveler also recently named Nashville one of the 20 best places to visit in the world in 2020, making it the eighth straight year the city has been named a top destination by national or international travel outlets.

It wasn’t a “Build It and They Will Come” strategy that the city employed. Rather, Spyridon says, the demand for Nashville was always there; the city just didn’t have the tools to capitalize on it 20 years ago. “There’s a big difference between people already having an affinity for Nashville versus building something and praying we could fill it,” he says.

THE GULCH GENESIS

The focus on revitalizing the inner core of Nashville stretches back to the mid 1990s when former Tennessee Gov. Phil Bredesen was mayor. His successors, all Vanderbilt alumni—Bill Purcell, JD’79; Karl Dean, JD’81; and Megan Barry, MBA’93—continued those efforts to revitalize urban neighborhoods in various forms. The current mayor, John Cooper, MBA’85, is now left with a very different task: figuring out how to make booming Nashville as pleasant for locals as it is for the throngs of tourists who visit each year.

It wasn’t just mayors and Chamber of Commerce types who played a role in Nashville’s transformation, however. Perhaps one of the most influential figures to help reshape the city has been Steve Turner, who along with his son Jay and real estate attorney Joe Barker, JD’69, developed the neighborhood known as the Gulch starting in the late 1990s.

A long-derelict area near downtown, the Gulch most recently was named Nashville’s “chicest” neighborhood by The Wall Street Journal. It’s home to a hipster-fueled mix of properties that include trendy ramen and sushi bars and the luxurious Thompson Hotel, as well as the beloved-but-rundown Station Inn, once a regular haunt for bluegrass legend Bill Monroe.

Turner says his interest in transforming downtown Nashville began in 1995 after converting a stately, century-old brick building along Second Avenue into a five-story residence, only to discover that he had very few neighbors.

“We had probably about 100 people living downtown at the time … I didn’t have anybody to talk to,” Turner jokes. Part of the reason so few inhabitants lived downtown then was because the area had been restricted primarily to businesses. That meant the streets bustled during the daytime, but grew quiet, and a little dangerous, at night.

By 1997 the zoning laws had been changed, and Nashville was on its way to recovering from a “Hee Haw hangover,” as Turner puts it, referring to the cornpone variety show that ran on CBS and in syndication from 1969 until 1997.

It was around this time that Turner came across an opportunity to purchase a neglected 6.8-acre tract from railroad company CSX, located about 10 blocks away from the heart of Broadway. “It wasn’t a very glamorous part of town, of course,” Turner says of the Gulch, a utilitarian name he insisted on keeping for the area. “But there was a lot going on around it at the time.”

With an idea to adopt some of the principles of New Urbanism that he had seen in northeastern cities—building walkable downtown neighborhoods with dining and shopping nearby—Turner rolled the dice. For that first patch of land in the Gulch, Turner estimates that he paid about one-75th of what it’s worth today.

While he acknowledges the timing worked out in his favor, Turner is quick to say that “an awful lot of work” went into developing the area. Market Street Enterprises, the name of Turner’s development company, spent years on the invisible tasks of securing infrastructure and lining up the proper permits. The team enjoyed early success starting in the mid-2000s, but they soon encountered vast hurdles. The only two Gulch condominium projects the Turners developed—Icon and Velocity—both opened in the midst of the 2008–09 financial crisis. “It was the largest condo project in downtown Nashville,” Jay recalls, “and we had 418 units we had to sell.”

As corny as Jay Turner says it sounds, what helped the company persist through hard times was a mission statement Steve Turner had originally drafted for the Gulch, promising to develop a neighborhood that would have a positive and lasting impact on the city. “We built the Gulch to last a long time, and we still maintain ownership of our buildings,” Steve Turner says. “We didn’t get into these developments just to turn them over.”

Whatever ills Nashville’s popularity has wrought—more traffic, pedal taverns, and an influx of bachelorette and bachelor parties—the Gulch really did pave the way for other areas of the city to flourish.

Across the Cumberland River, East Nashville has fully developed into an epicenter of cool—a kind of artistic offshoot of Nashville proper. Along Charlotte Pike, the Sylvan Park area has transformed into one of the most attractive parts of town, combining remodeled historic homes with some of the city’s newest restaurants. The area around 12th South is all but unrecognizable compared to just a decade ago, fueled in part by boutiques opened by actress and Nashville native Reese Witherspoon and singer–songwriter Holly Williams, daughter of Hank Williams Jr. Just north of Broadway sits historic Germantown, which is home to a new minor league ballpark and some of the city’s most celebrated restaurants; it’s also become one of the highest-priced neighborhoods in Nashville.

Yet it could be argued that, had it not been for the urban-infill example set by the Gulch, none of these neighborhoods would have taken shape as they did.

Jay Turner says his father often lamented the fact that most Southern cities developed in a doughnut shape, in which you just drive in concentric rings further and further out of town. “He always said, ‘I want Nashville to be a Danish instead so that the sweetest part is in the middle. ’ ”

It appears that he got his wish—and, finally, some downtown neighbors.

Health Care Hotspot

Music, tourism and major league sports may be the industries in Nashville that grab the most attention, but, in economic terms, Nashville’s health care companies dwarf them all.

The city occupies a central role in the nation’s health care spending, which accounts for upwards of 20 percent of U.S. GDP. Specializing in health care delivery, many of the companies headquartered in Nashville manage national chains of hospitals and related facilities. Vanderbilt University Medical Center complements that industry cluster as one of the nation’s foremost academic medical centers, while also providing complex and high-level trauma care in a multistate region.

Health care contributes around $47.6 billion of economic impact in the Nashville area each year. Globally, the city’s health care companies generate more than $92 billion in revenue and more than 570,000 jobs.

“Part of the Nashville story gets a little bit lost because you don’t have that national branding for a lot of the huge headquarter companies that are here,” says Hayley Hovious, MBA’08, president of the Nashville Health Care Council. “Yet Nashville is unquestionably the center for health care services in the U.S. … Nashville has more purchasing power than anywhere in the country when it comes to medical devices, medical hardware and medical software.”

The company that single-handedly sparked Nashville’s health care industry is HCA Healthcare, founded in 1968 by Dr. Thomas Frist Sr., MD’33, his son Dr. Thomas Frist Jr., BA’61, and businessman Jack Massey.

Today, HCA Healthcare owns and operates 185 hospitals and 119 freestanding surgery centers in 21 U.S. states and in the United Kingdom. It is No. 67 on the Fortune 500 with annual revenues of $46.7 billion. Two other Nashville-based companies founded, or co-founded, by former HCA executives also occupy spots on Fortune lists, Community Health Systems (No. 223) and Acadia Healthcare (No. 763).

In all, Hovious estimates that about 500 companies based in Nashville work in some aspect of health care delivery, while another 400 firms provide professional services, such as accounting, legal counsel and consulting, to the industry.

For its part, VUMC treats nearly 2.5 million patients at 33 locations in the region each year, including $613 million in charity care. It supports nearly 60,000 jobs, contributing $2.8 billion in labor income to the local economy. In addition—and perhaps as important—Hovious says Vanderbilt’s status as a globally renowned research institution attracts attention from health care leaders around the world. She points to the Nashville Health Care Council’s Fellows initiative, a highly competitive executive development and networking program co-created by Larry Van Horn, an associate professor at the Owen Graduate School of Management, and former U.S. Sen. Dr. Bill Frist. Hovious says faculty and others associated with Vanderbilt also regularly help facilitate far-flung introductions between researchers, executives and investors.