https://youtu.be/xUEDsJqxlwo

Finds include household items from medieval Islamic period and a portion of a temple built by King Herod

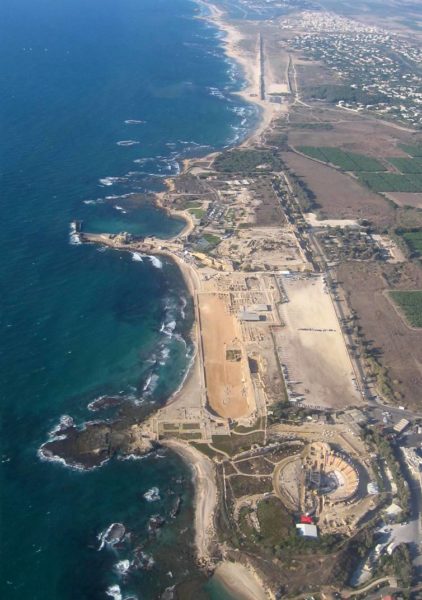

Over the past two years, Vanderbilt researchers and students working at the ancient port city of Caesarea, on the north coast of modern-day Israel, have unearthed tantalizing clues to life in the city during the medieval Islamic period as well as the best-preserved remains yet discovered of Herod the Great’s Temple of Rome and Augustus. These finds shed light on an oft-overlooked period in Mediterranean history and give scholars a fresh look at a world-famous monument destroyed long ago.

Under the direction of Joseph Rife, director and associate professor of classical and Mediterranean studies, and Phillip Lieberman, associate professor of Jewish Studies and Classical and Mediterranean Studies, an international team of Vanderbilt students, staff, faculty and archaeological specialists have been excavating a 900-square-meter section of the ancient and medieval port city during the Maymester sessions of 2018 and 2019. They work at the site, which is a national park, in collaboration with the Israel Antiquities Authority.

Home to the mercantile elite

“Caesarea is one of the most important sites in the region, dating back to antiquity,” said Lieberman. “It was a huge, cosmopolitan trading center, on par with medieval Baghdad and Damascus and, before that, ancient Alexandria and Antioch.”

Beginning in 2018, the Vanderbilt students opened a series of regularly spaced trenches on a plot of land just off the city’s main thoroughfare, right in the city center.

“One of the first things we found was a very opulent residential district dating back to the 10th to 12th century of the common era—what we call the Islamic Middle Ages,” said Rife. They ultimately uncovered the remains of two compounds that likely housed two extended family households.

Rife described the homes as urban mansions, housing the richest residents of the city during a period when Caesarea was booming. The structures contained elaborate, well-preserved mosaics, glazed and decorated pottery, imported glassware and finely carved bone used for the decoration of expensive furniture—all indicators of high social status during the period.

Another clue to the residents’ status was their sophisticated plumbing, said Lieberman. “There were enormous cisterns, large enough to stand up in,” he said. “This is a very arid part of the world, which means access to water is highly prized. The presence of these sophisticated waterworks tells us these families were quite wealthy.”

And perhaps most importantly, the students discovered a horde of gold coins—a rare find—minted locally around the year 1055 during the rule of the Fatimid Caliphate, which was expanding north and east from Egypt toward Mesopotamia at the time.

While no religious items have yet been found at the site to indicate the faith of the residents, Rife said that the objects they have found reflect the lifestyle of wealthy Muslim merchants of the period.

Temple of Rome and Augustus

Once a wonder of the ancient world, the massive, first-century-B.C.E. shrine to the Roman Empire and the Emperor Augustus dominated the city’s skyline until it fell into ruin and was replaced by a cathedral during the 5th century C.E. Today, all that remains is the stone platform upon which the structure once stood.

The Vanderbilt excavation site abuts the platform, and the team stumbled upon a portion of the outer wall quite by accident. The wall is made of expertly dressed stone—local sandstone hand-carved into blocks with clean edges—and is in better shape than any other part of the temple found to date. “It’s perfectly preserved,” said Lieberman. “It looks like it could have been built yesterday.”

The wall likely has an important connection to the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, too, added Rife. “Herod was a famous builder during his reign, and we know that he used the best structural engineers in the region,” he said. “And these might well have included the same builders who renovated the Temple Mount and erected its famous Western Wall. So by exploring this new area of the temple platform at Caesarea, we can also learn more about the building techniques used to construct one of the world’s most important religious structures.”

Looking forward

In addition to analyzing the artifacts they discovered, Rife and Lieberman are working with colleagues in the U.S. and Israel to design an integrated digital archive of historical and archaeological evidence so that scholars, students and the public alike can learn about Caesarea online. They’re also looking forward to continuing the excavation with another group of students this coming May.

“The archaeology of medieval Islam is a relatively young field in the Near East, as most such work in the region has traditionally concentrated on earlier eras and the biblical narrative,” said Rife. “We have a lot of textual records for society and economy during the medieval period, such as business records and wills, and now we’re finding archaeological parallels to all of those documents. It’s very exciting. Vanderbilt’s work at Caesarea will help to write a new chapter in the history of the region.”

This research was funded in part by a Discovery Grant, which advances new ideas and cutting-edge scholarship in the university’s core disciplines.

(click any image to enlarge)