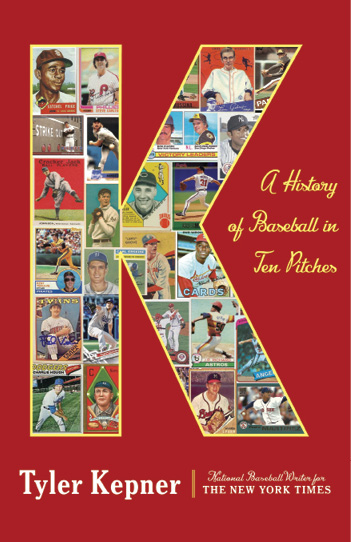

By Tyler Kepner, BA’97

Baseball people like to say that your worst day at the ballpark is better than your best day at the office. It reminds them that the baseball life is really not too bad. Yes, it’s stressful, with relentless travel and meager pay in the minors. But somebody wins every day, you’re outdoors a lot, and deep down you recognize that, of all the industries out there, you’re lucky to work in the baseball one.

Maybe for that reason, I’ve found that most people in baseball tend to be … pretty nice. And of all the subsets of folks in the game, knuckleball pitchers might be the nicest. They are also part of the smallest group, which helps explain it. Almost all knuckleballers were rejected by the game before they could last very long. They earned their living by grabbing the wing of a butterfly and then, somehow, steering it close enough to the strike zone, again and again, to baffle the best hitters in the world.

“Most of our careers were headed in a different direction, and out of desperation, we all found the knuckleball,” says [longtime Boston Red Sox pitcher] Tim Wakefield, who won 200 games with it. “So I think the knuckleball itself has humbled most of us to a point where we’re grateful that we still have a job and we’re still able to compete.”

“Compete” is the word Charlie Hough uses to explain his reason for throwing it. Hough was a decent pitcher in Class A for the Dodgers, but after six months in the Army Reserve, his shoulder hurt when he tried to pitch again. With average stuff to begin with, Hough guessed his future would be working at the Hialeah Race Track, two blocks from his home in Florida.

Then a scout named Goldie Hold showed him how to throw a knuckleball. Hough gave it a try.

“If you want to compete, you compete,” he says. “You find something.”

That something, for Hough and just a few dozen others in baseball’s long history, is a pitch as quirky as its name. Pitchers once threw it with their knuckles actually pressed against the ball, and the knuckles are still prominent in the visual presentation. But the pitch is really thrown with the fingertips—“positioned between the thumb, index and middle fingers,” as Wakefield wrote in his book with Tony Massarotti, “as if it were a credit card being held up for display.”

The whole concept of the knuckleball is to be fundamentally different from every other pitch. With almost everything else, pitchers want to increase spin for greater velocity or a more deceptive break. They manipulate the ball to serve their will, to send it to a specific spot. If executed properly, the pitch will obey.

Because knuckleballers want no spin at all, they don’t engage the same muscles as conventional pitchers. If a robot could pitch, it would throw like a knuckleballer, like one mechanical piece instead of a flexible acrobat stressing multiple leverage points to impart spin. The physical dangers of repeated throws at maximum effort do not apply for these craftsmen. Theirs is the safest pitch of all, but the trade-off is severe: It is also the hardest to master, and to trust.

Simply put, the trick is to use the seams to deflect the air and move the ball erratically, like an airplane flying into turbulence. A University of Iowa study, cited by the author Martin Quigley, described the aerodynamics like this: “When the ball leaves the pitcher’s hand, it runs head-on into a ‘wall’ of air. This air also tends to ‘pile up’ on the seams and rough surfaces. The forces holding the ball back build up so fast that the ball slows down suddenly and drops unusually fast … usually a short distance in front of the plate, and causes the batter to swing ‘where it was, not where it is.’”

This results from what is known, in science, as Bernoulli’s principle, which states that the pressure within a flowing fluid (including a gas, such as air) is less than the pressure surrounding it. An object that is not spinning—or just barely spinning—will move toward an area of less pressure. As Robert K. Adair wrote in The Physics of Baseball, the seams on a ball create chaos: “If the ball is thrown with very little rotation, asymmetric stitch configurations can be generated that lead to large imbalances of forces and extraordinary excursions in trajectory.”

Then we have the unofficial explanation, from the batter’s box, by the longtime outfielder Bobby Murcer. Trying to hit Phil Niekro, Murcer memorably said, was “like trying to eat Jell-O with chopsticks.”

A good knuckleballer will leave you laughing and stupefied, like a comedian who also does magic tricks; Satchel Paige called his the “bat-dodger.” The pitch has a deep and rich history in the game, yet remains so uncommon that it is often an object of ridicule.

Sometimes the teasing is playful: In Wakefield’s heyday with the Boston Red Sox, catcher Mike Macfarlane would cry “Freak show!” in the clubhouse before games. Sometimes, it is not so much teasing as a deep dislike, for practical reasons. Joe McCarthy, the Hall of Fame Yankees manager, groused that when a knuckleball breaks, the catcher misses it, and when it doesn’t, the batter crushes it. He had little use for pitchers who did not throw hard.

“Any time you’ve got a soft ball pitcher,” McCarthy would say, “then you’ve got a .500 pitcher.”

Hough was .500 personified, with a career record of 216-216. Nobody else with that many victories has precisely the same number of losses. Then again, nobody else has made 400 appearances as both a starter and reliever, and few others have spent a quarter-century on major league mounds.

Hough is a very nice guy, too. Bobby Valentine, who was teammates with Hough in Los Angeles, managed him in Texas, and hired him as a coach in New York, called him one of the best baseball men in the world. But Hough was not simply happy to be there. Nice does not mean pushover. Floating knuckleballs for a living takes a special kind of athletic bravery.

“I think you need a huge ego,” Hough says. “You need to believe that you’re the best pitcher in the world when you’re in there. When they put down ‘1’ for Nolan Ryan, he threw it 100 miles an hour. When they put down ‘1’ for me, I threw what I felt was a pitch they couldn’t hit.”

Adrenaline is the enemy. If you overthrow a knuckleball, it spins—and if it spins, you’re in trouble. Trusting it defies logic, but doing so is essential. The pitchers who throw it do not frustrate easily. They need to stay calm so their pitch will behave. Low-key, happy-go-lucky people—with the guts to bring Silly String to a battlefield—just might have a chance.

The knuckleball is, at once, the most frustrating and fascinating pitch in baseball. It is also relatable, much more than any other pitch, to the fan in the stands. No one sees a turbocharged fastball and thinks: “Yep, I could do that.” Yet anyone can look at a dancing knuckleball and say, “You know what? Maybe.”

But the premise that anyone can become a knuckleballer? Well … it’s dead wrong. There are many reasons the pitch always flirts with extinction, but the most fundamental is this: It’s really, really hard to throw. Fastball pitchers are born; knuckleball pitchers are painstakingly self-made.

“People watch us throw and they say, ‘Oh, that’s easy,’” Wakefield says. “Throwing it 65 or 70 miles an hour, anybody could do that. But in reality, it’s really hard. And to be able to throw it for strikes consistently, that’s the big thing. I mean, every middle infielder had a good knuckleball—but can they get on the mound and throw it to a hitter with a game on the line?”

Indeed, plenty of position players fool around with knuckleballs while playing catch—Mickey Mantle and Cal Ripken Jr. were well-known for it, and R.A. Dickey, who won the 2012 National League Cy Young Award, says a different teammate would find him every year to show off his version.

But pitching from the slope of a mound makes it harder to keep the palm behind the ball, and changes everything. And even if a pitcher has the patience and the temperament for it, the knuckleball still requires the same kind of extraordinary athleticism as any other pitch—that is, the ability to repeat sound mechanics. This delivery is just engineered differently, for a much different kind of result.

“From your shoulder down you’re all stiffed up, everything’s locked in, there’s no flip of your wrist,” says Phil Niekro, the greatest knuckler of all. “In baseball—curveball, slider—it’s all what you do with your wrist and the movement of the ball, the spin of the ball. Here, you want to throw something that’s not gonna do anything at all, and you figure: ‘What the hell, it’s not doing nothing, but it’ll do more than any other pitch you throw up there.’”

By doing nothing, the pitch with no spin can do anything.