A team of Vanderbilt University earth scientists returned to an unusual cave in India to unlock secrets about climate change that could have far-reaching implications.

By studying the last 50 years of growth of a stalagmite from Mawmluh Cave in the northeastern Indian state of Meghalaya, an area that experiences so much summer monsoon rainfall that it is credited as the rainiest place on Earth, they found an unexpected connection between winter (dry season) rainfall amounts in northeast India and climatic conditions in the Pacific Ocean. Winter rainfall following weak monsoon years can alleviate water stress for farmers in India. This distant link between land and ocean records could aid in predicting dry season rainfall amounts in northeast India.

Each year, monsoon rains between June and October provide water for roughly 1.5 billion people in India and beyond. Changes in monsoon strength and the timing of its onset or withdrawal can trigger either drought or flooding, with devastating consequences, highlighting the need for effective ways to predict and prepare for rainfall variations.

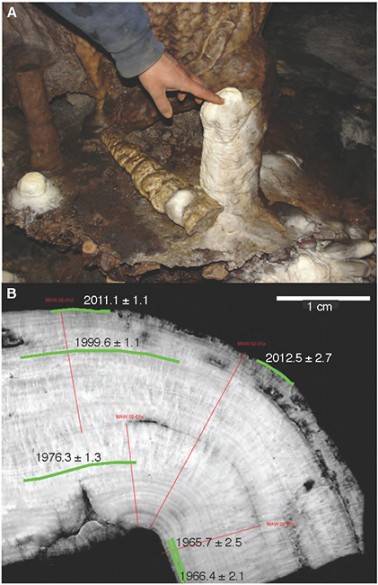

Stalagmites from Mawmluh Cave and the surrounding region indicate the recurrence of intense, multi-year droughts in India over the last several thousand years. In fact, stalagmite records from monsoon regions such as India are vital to understanding past variability in the global climate system and the underlying reasons for this variability. Scientists typically look to those records to reflect changes in the amount of monsoon rainfall and changes in monsoonal circulation in the atmosphere. The potential influence of rainfall during winter is often overlooked.

“Counterintuitively, air and water circulation in caves can cause, and even favor, stalagmite growth in the dry season, leading to unexpected effects in paleoclimate records,” said Elli Ronay, a Ph.D. student in Vanderbilt University’s Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences.

In a recent paper published in the journal Scientific Reports, Ronay, Jessica Oster, assistant professor of earth and environmental sciences at Vanderbilt, and Sebastian Breitenbach of Ruhr University Bochum, Germany, detail their sub-seasonally resolved reconstruction of trace element compositions from the Mawmluh Cave stalagmite, providing information about local changes in hydrology. Comparisons of cave records and nearby rainfall data show that variations in dry season rainfall rather than the monsoon rains govern variations in trace element concentrations in the stalagmite and how the amount of variation changes from year to year.

This finding likely extends to stalagmite records from other caves with seasonal hydrology or ventilation, especially in monsoon regions. For Mawmluh Cave, the new study identifies links to a cycle known as the Pacific Decadal Oscillation and can help predict dry-season rainfall.

These new results advocate for caution when interpreting stalagmite records from regions characterized by strong seasonality like the monsoon. They also suggest that potentially powerful information about annual rainfall variability in northeast India has gone unnoticed in stalagmite records thus far.

The work was funded Vanderbilt Discovery Grant, the Geological Society of America and a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under grant DGE-1445197.