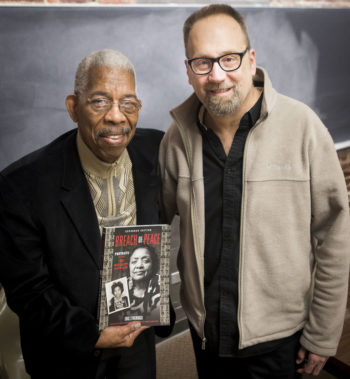

Eric Etheridge and rider Rip Patton Jr. meet with students

Significant lessons from the 1961 Mississippi Freedom Rides and their absolute relevance to today’s racial and social justice movements were among topics that alumnus, author and photojournalist Eric Etheridge, BA’79, and Freedom Rider Ernest “Rip” Patton Jr. discussed with students during a campus visit Jan. 28-29. The visit was co-sponsored by Vanderbilt University Press and Residential Colleges.

Etheridge created the photo-history book Breach of Peace (Vanderbilt University Press, 2018), which includes mug shots of 329 Freedom Riders arrested in Jackson, Mississippi, and side-by-side contemporary portraits of the 99 he located. Breach of Peace also has brief bios of those 99 riders and extended interviews with alumnus James M. Lawson, C.T. Vivian and other activists.

While the Freedom Rides took place across several Southern states, the majority of the riders ended up in Jackson, Mississippi, about 60 miles from Etheridge’s hometown of Carthage. He was only 4 years old at the time of the rides, but has vivid memories of segregation in everything from schools to movie theaters.

“It’s important that we remember as Southerners—and as Americans—what the courageous Freedom Riders endured back then, including prison sentences,” Etheridge said. He noted that about a third of all the riders who went to Jackson were from the Deep South, and all but three were black. “Many of the Freedom Riders, such as those in the Nashville Student Movement, had previous experience with protesting,” he said. “Others were motivated by the media coverage of the arrests they had seen on television and in print publications like Life magazine.”

Etheridge said that he was looking for a new project with historical images when he came across the Freedom Riders’ mugshots in longtime sealed files of the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission. For many years, the now-defunct commission was a powerful state agency with investigative powers. It was created after the Brown v. Board of Education ruling that found separate public schools for black and white students to be unconstitutional.

“The Sovereignty Commission worked closely with the police to keep an eye on civil rights protesters and maintain detailed files on them,” Etheridge said. “So in an ironic twist, the commission has provided an incredible record of how the Freedom Riders were treated in Mississippi.”

Etheridge, who majored in English at Vanderbilt, did a first edition of the book in 2008 with just over 80 contemporary portraits. Then several Freedom Riders whom Etheridge had not located earlier came forward. “Hearing their family stories along with their educational and occupational experiences has brought this early civil rights era to life in a way that I continue to find fascinating,” he said.

While on campus, Etheridge and Patton, who grew up in Nashville, took part in a first-year writing seminar taught by Dennis Dickerson, the Rev. James M. Lawson Jr. Professor of History. The seminar focuses on how Mohandas K. Gandhi’s non-violence movement to end British colonialism in India reverberated globally, including the U.S. civil rights movement.

Patton noted that Lawson, a Vanderbilt University Distinguished Alumnus, began a weekly nonviolence workshop in 1959 from which the Nashville Student Movement emerged. Patton attended Tennessee State University and was active in the Nashville movement. He still lives in Nashville and volunteers in the Civil Rights Room at the Nashville Public Library.

“What I took away from Patton’s presentation is that in order ‘to get the ball rolling,’ we have to communicate better with each other,” said Kaylin Davis, a first-year student who has been active in juvenile justice reform and political advocacy in Chicago and Nashville. “We need to communicate—not just through a mass production of messages—but through people. That’s how we’re going to change lives.”

In addition to the class visit, Etheridge visited the Career Center, where he spoke to students about his career journey.

That evening, Patton and Etheridge met with students at E. Bronson Ingram College for a dinner and discussion about the impact of the Freedom Riders. “The Residential Colleges provide our campus with unique spaces for these types of interactions, where students from different majors and backgrounds can learn from guests and listen to each other,” said Vanessa Beasley, associate provost and dean of residential faculty.

The community can view selected “then and now” portraits from Breach of Peace in the Bronson art gallery.