By Michael Blanding

The story made the rounds of social media in an internet minute: Smiling and wearing T-shirts reading “I Got Chipped,” 40 employees of a company in Wisconsin voluntarily received microchips embedded beneath the skin of their hands last year. The company touted the new cyber implants as a convenient way for its workers to log on to their computers and order food from the cafeteria, and predicted that one day the microchips could be used for everything from air travel to medical records.

Elsewhere, however, the practice was condemned, as Twitter erupted with warnings about an Orwellian Big Brother and Skynet, the dystopic neural network in the Terminator movie franchise, and privacy activists urged a boycott of the company. Outside the firm’s gates, Christian fundamentalists showed up to protest the chips as the “mark of the beast” that will usher in the end times.

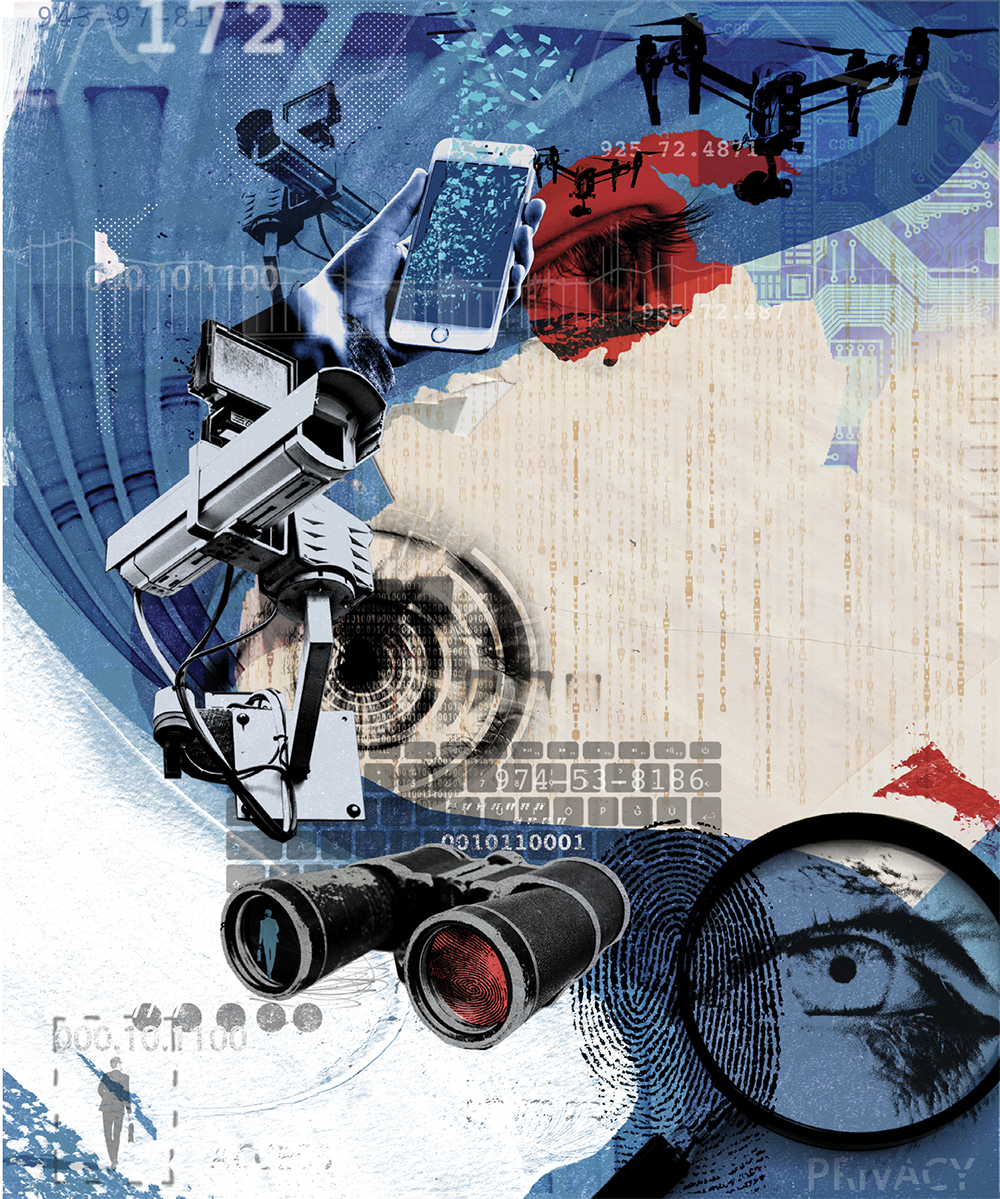

In an age of Cambridge Analytica, uncanny Facebook algorithms and NSA wiretapping, it seems every time we turn around, there is a new assault on that once most precious of commodities: our privacy. In reality, however, what we choose to reveal and what we keep private has long been a source of debate, with as many people choosing to sacrifice their privacy in exchange for perceived social benefits as those lamenting the increasing intrusions into their private lives.

“Some amount of privacy is always going to be lost when you’re a member of society,” says Sarah Igo, associate professor of history, law, political science and sociology and director of the American Studies program at Vanderbilt, “but in a modern, technologically advanced, capitalist and democratic system where people believe they have the right to set the rules to some degree, you get this really rich set of debates around just where that line should be.”

“Some amount of privacy is always going to be lost when you’re a member of society,” says Sarah Igo, associate professor of history, law, political science and sociology and director of the American Studies program at Vanderbilt, “but in a modern, technologically advanced, capitalist and democratic system where people believe they have the right to set the rules to some degree, you get this really rich set of debates around just where that line should be.”

Igo chronicles the shifting course of that line in her new book, The Known Citizen: A History of Privacy in Modern America (2018, Harvard University Press), examining our fraught relationship with both confidentiality and exposure. Since its publication in May, the book has received positive reviews in The Washington Post, The New Yorker, Harper’s, and The New York Review of Books.

At the same time, Igo has been lending her historical perspective to a cutting-edge debate as a member of Vanderbilt’s GetPreCiSe (Center for Genetic Privacy and Identity in Community Settings)—established with a four-year, $4 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to explore issues of privacy around genetic medicine.

EARLY CONCERNS

Igo argues that privacy concerns are nothing new—in fact, Americans have been struggling with the relationship between public versus private from the beginning. Rather than tracing a straight path from complete privacy to complete exposure, the course of privacy in the U.S. has ebbed and flowed over time, as Americans have responded to social problems, corporate and state demands, and technological innovations.

“I hope the book challenges simple notions that we used to have a lot of privacy and now we no longer have it. Or that all our dilemmas around privacy would be solved if Facebook or the state would just behave better and observe their bounds,” Igo says. “This is really a social and political question—a dilemma and a puzzle that only exists because there have always been good reasons for invading our privacy.”

Case in point, 80 years ago the country exploded with controversy over another tracking device: Social Security numbers. When the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration first proposed the idea of registering 26 million workers for retirement benefits, Republican opponents and the tabloid press alike railed against the unconscionable invasion into privacy, warning that the government would ask invasive questions about church affiliation and marital status.

“Your life will be laid bare,” one newspaper warned. “You are to be regimented—catalogued—and put on file.”

In fact, already alert to public sensitivities, Social Security required only the bare minimum of information, rejecting practices like fingerprinting even though it would have made its identification processes more reliable. Within just a few years of their adoption, however, citizens were embracing Social Security numbers as a mark of security in troubled economic times. They even began buying rings and other jewelry proudly displaying their numbers. And in the ultimate sign of pride, some people tattooed their Social Security numbers on their bodies—an image even more shocking to modern sensibilities than getting a microchip implanted into one’s hand.

“The SSN is one of the things we think of as being fundamentally private, and that we guard very carefully, but Americans in the 1930s were making it very public,” Igo says. For them, the number represented not so much an intrusion into their privacy, but rather a validation of their identity. “It was a kind of badge of national belonging or citizenship—almost a declaration of their rights as Americans to economic security.”

Igo identifies herself as an intellectual and cultural historian, tracing the history of ideas rather than battles and borders. She grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area, a voracious reader from early on. “I remember my parents actually banning me from reading at the dinner table and on vacations,” she recalls.

As an undergrad at Harvard, she studied social theory, looking at how texts ranging from Marx and Freud to adolescent series such as Sweet Valley High and The Babysitters Club influenced ideas about female identity and desire. Teaching history at Phillips Academy Andover after graduation, she saw how intertwined such ideas are with specific historical moments.

“I became really interested in historicizing ideas and culture, and asking how people change their minds and why,” she says.

In the case of privacy, the first shifts came at the end of the 19th century. Before that, says Igo, privacy was often a material concern, centered on a person’s home and property. But a convergence of factors in the 1880s—including an aggressive tabloid press and new technologies from instant photography to the telegraph and telephone wires that could suddenly transmit someone’s image or voice long distances—changed that.

“It’s the first real moment of privacy going virtual,” says Igo. “What fascinated me were all the parallels to what’s going on a century later. Technological innovation in that case, as now, seemed to be driving the conversation on privacy.”

The crisis came to a head by 1890 with an influential Harvard Law Review article by Louis Brandeis and Samuel Warren that first identified a “right to privacy” around a person’s “inviolate personality” to prevent their private lives being exposed to the world.

Exactly what the “right to privacy” entailed, however, would be up for debate for decades, with countless political fights over who had a right to privacy, and from what.

LATER REVERSALS

From the beginning it was clear that some Americans—women, ethnic minorities, prisoners, gays and welfare recipients among them—were not given the same consideration for privacy as white men. Under the guise of public health, for example, poor workers and minorities were subject to invasive “sanitary surveillance” detailing their family habits in intimate detail, while new immigrants were fingerprinted as a public security measure to protect against supposed subversive elements.

As the 20th century unfolded, controversies broke out in many different domains, with citizens leery of psychological and personality testing in the 1950s, the computerization of government and commercial records in the 1960s, and exposés of FBI surveillance in the 1970s. Positions around privacy could also be fluid, however. Gay men, for example, dreaded exposure by law enforcement in the 1950s and ’60s, but after the Stonewall riots in 1969, they came out themselves to proudly make their sexual identities public.

“These reversals were about who privacy belonged to, what privacy was doing, and what kind of power was being exercised in its name,” Igo says, “whether it was gay men who wanted privacy and then rejected it in certain ways, or feminists who made the claim that privacy could be a power play that allowed men to do what they wanted to the women in their lives.”

Surprisingly, a constitutional right to privacy didn’t exist in America until 1965. That is when the Supreme Court ruled in the influential Griswold v. Connecticut case, striking down a state law banning the use of contraceptives by married couples. While the court ruled for the first time that a “right to privacy” existed, the fact that it was presented in the context of birth control forever strongly shaped its future course, says Igo.

“It meant that in the United States, privacy got attached to reproductive rights and sexual freedom,” she says. While privacy was used as rationale for legalizing abortion and overturning sodomy laws, a more overarching protection from government and corporate surveillance never materialized.

“Citizens today don’t really have a lot of say-so in establishing these public–private lines,” Igo says. “There are powerful organizations, both corporate and state, that have demanded to know certain things about citizens, and people often believe they have no choice but to go along.”

Erosions of privacy are almost always justified as having a good social purpose—making us safer or giving us more convenience. “And because we have no guiding principles in the United States beyond a patchwork of specific laws, it’s very hard to assess the cumulative effect of all these different practices,” she says.

In the case of social media, for example, users have to weigh the benefits of connectivity and targeted advertising against the costs of giving up an unprecedented amount of personal information about their private lives—a case not too dissimilar from the debate about Social Security in the 1930s. “We have to be known in order to get certain things,” Igo says, “yet we want to preserve some freedom and ability to decide what we want to reveal.”

CURRENT DEBATES

Those tensions also inform the current debate around use of genetic information, which promises on the one hand to enable new individualized diagnoses and treatments, and threatens on the other to facilitate tracking and discrimination. Because of the history of suspicion of government surveillance, says Igo, people so far have seemed more comfortable giving private genetic information to companies such as 23andMe or Ancestry.com, which are almost completely unregulated, rather than public entities such as the National Institutes of Health.

“Rightly or wrongly, the state is held to a different standard than private commercial entities,” she says. “There is a willingness to allow corporations to do things that the government could never get away with.”

Currently, she is involved in several projects with Vanderbilt’s GetPreCiSe Center to dive deep into people’s perceptions around genetic information and privacy. The center is conducting a large survey to better understand public opinion, as well as looking at how genetics are represented in film and popular culture, and doing additional work on how minority communities encounter and perceive genetic medicine.

“Her work is really informative in that we can better comprehend the historical events that underlie our current understanding,” says the center’s co-director, Ellen Wright Clayton, the Craig–Weaver Professor of Pediatrics and a professor of law.

The fact that so many people are putting out their genomes publicly on the web to match with ancestors, for example, was perplexing to Clayton until she heard from Igo that people once tattooed Social Security numbers on their bodies. “Sarah provides a different perspective than how I would have thought of it.”

The GetPreCiSe Center is also examining legal policies, such as the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008, which prohibits some uses of genetic data. Igo’s input helps to better explain the context of how such laws developed out of our country’s convoluted thicket of privacy laws, says the center’s other co-director, Brad Malin.

“Policy is not made in a vacuum,” says Malin, a professor of biomedical informatics, biostatistics and computer science. “It’s usually an artifact of how issues have played out over time.”

As genetic medicine continues to take hold in the U.S., Igo hopes the center’s research can help to get in front of the debate, recommending policies that will benefit citizens and also protect what for many is highly intimate information—their DNA. “History only goes so far in guiding us as to specific policies, but what history does suggest is that we cannot sit back and wait for states or corporate entities to self-regulate,” she says.

In past debates, citizens have made a difference, for example, in defeating proposals for a national fingerprint registry and universal ID cards. No matter what policies are enacted, however, it’s clear that hard choices will have to be made regarding how much we want to give up and how much we want to keep secret.

“Engaged citizens,” Igo says, “need to be willing to take up these questions and make tough decisions.”

Michael Blanding is an award-winning Boston-based investigative journalist whose work has appeared in The New York Times, WIRED, Slate, The Nation and The Boston Globe Magazine, covering politics, social issues and travel. Currently, he is a senior fellow at the Schuster Institute for Investigative Journalism at Brandeis University. His latest book, The Map Thief (2014, Gotham), was a New York Times Bestseller and an NPR Book of the Year.

Vanderbilt professors advise Facebook data research initiative

Elizabeth Zechmeister, Cornelius Vanderbilt Professor of Political Science and director of the Latin American Public Opinion Project, and Noam Lupu, associate professor of political science and associate director of LAPOP, have been named advisers with Social Science One, an independent research commission investigating the impact of Facebook on democracy around the globe.

Social Science One was co-founded by Harvard’s Gary King and Stanford’s Nathaniel Persily in response to revelations of personal data misuse by Cambridge Analytica and others in recent years. It is designed to provide an ethical framework for conducting social science research using private industry data that also preserves academic freedom. Facebook announced its intention to become the commission’s first industry partner in April.

Social Science One serves as a third-party mediator between industry and potential researchers. It is composed of distinguished academics who have access to Facebook’s proprietary data, while also having the expertise to understand what kind of data would be useful to the academic community. The commission, not Facebook, identifies the data sets made available to scholars and develops requests for proposals based on those data sets. The first data set was an aggregate list of public links shared across the platform. More data sets are forthcoming.

Zechmeister and Lupu serve on the regional advisory committee focusing on research involving Latin America. One of the first data sets to come out with input from that group focused on the recent presidential election in Mexico.

Before receiving funding and access to data, academics who submit proposals not only must meet the requirements of peer-reviewed social science, but they also must pass a rigorous ethical review process developed explicitly for research involving personal data. This peer-review process for the Facebook partnership is administered by the Social Science Research Council. Facebook will not review the research before it is published.

To preserve a nonpartisan research agenda, Social Science One is funded by an ideologically diverse group of seven nonprofits. Visit socialscience.one for more information about the commission.

—LIZ ENTMAN