By Frye Gaillard, BA’68

A little more than two months after he spoke to nearly 11,000 people at Vanderbilt’s 1968 student-led Impact Symposium, presidential hopeful Robert Kennedy won the crucially important Democratic primary in California. In his new book, A Hard Rain: America in the 1960s (2018, New South Books), Frye Gaillard, who served as Impact’s chairman and Kennedy’s host at Vanderbilt, writes about that fateful night in California.

June 4, 1968—As 42-year-old Robert Kennedy passed through the hotel kitchen, he paused to shake hands with the staff, including Juan Romero, a 17-year-old busboy from Mexico. Two nights earlier, Romero had delivered a room service meal to Kennedy’s suite, and was forever impressed by Kennedy’s response—the strength of the grip as they shook hands, the respectful kindness of Kennedy’s manner as the two of them chatted briefly.

“He made me feel like a regular citizen,” Romero said later. “He made me feel like a human being.”

Finally, around midnight, Kennedy arrived in the ballroom and began to thank everybody he could think of. … He talked about the members of his staff and the black and Latino citizens of California … the list went on like some kind of acceptance speech at the Oscars, until he ended finally with words that would soon be broadcast again and again:

“So my thanks to all of you, and on to Chicago, and let’s win there.”

As he turned and re-entered the hotel kitchen, Sirhan Sirhan, an angry Palestinian whose motives for the deed were never clear, waited for him with a .22-caliber pistol. Juan Romero, in a rush of exuberance, reached out to shake Kennedy’s hand again, and in that moment he heard a popping sound. He saw the man who had made him feel human slump to the floor. As others wrestled the gun from Sirhan, Romero knelt beside Kennedy, who looked up at him and spoke his last words: “Is everybody OK?”

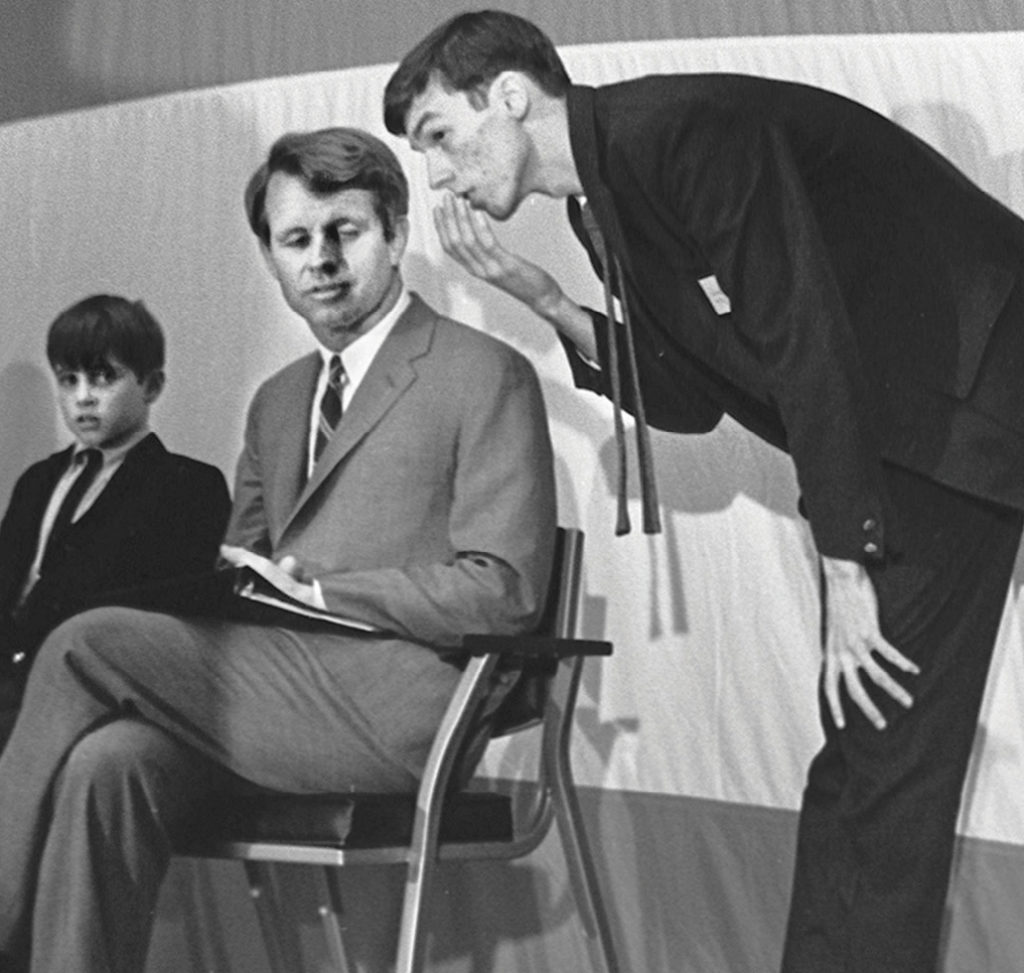

People have struggled in the months and years since then to describe the import of those final seconds. I remember thinking, like Romero, of a tiny personal moment—a time I shared the backseat of a car with Kennedy and his friend, astronaut and future senator John Glenn, on a 20-minute ride to Vanderbilt University. Somehow, I had known that one of his sons—I think it was Matthew, but can’t remember that for sure—had been sick, and I asked Kennedy how the boy was doing.

“He’s better,” the senator said. “He’s had a rough time, but he’s doing better.”

As the conversation began to drift to other topics, Kennedy turned back to me. “Thank you for asking that,” he said.

It was, of course, a small and ordinary exchange, but somehow for me it injected something personal into the hemorrhaging sadness I shared with millions—with the tens of thousands of every race and class who lined the tracks as his funeral train made its way into Washington, and with Sen. Edward Kennedy, who choked out a eulogy at the funeral: “My brother need not be idealized, or enlarged in death beyond what he was in life, to be remembered simply as a good and decent man, who saw wrong and tried to right it, saw suffering and tried to heal it, saw war and tried to stop it.”

For me, the most wrenching summation came from Romero, the busboy who knelt in the blood of Robert Kennedy—and who, incidentally, died recently at age 68—because, he said, “I wanted to protect his head from the cold concrete.” Later he told the Los Angeles Times the truth of what he learned in that moment—a truth from which the country has not yet recovered.

“No matter how much hope you have, it can be taken away in a second.”

Frye Gaillard, BA’68, writer in residence at the University of South Alabama, is former Southern editor at The Charlotte Observer, where he covered Charlotte’s landmark school desegregation controversy, the ill-fated ministry of televangelist Jim Bakker, and the presidency of Jimmy Carter. He has written or edited more than 25 books on Southern culture and history.

Watch Robert Kennedy’s Impact Symposium speech: