By Thomas Alan Schwartz

Fifty years ago, in the middle of a typically hot and humid Nashville summer, a Metropolitan Life Insurance manager named Paul Simpson sat with Frank Grisham, director of the Vanderbilt University library, in the rare books room of the main library building.

Using three Ampex video recording machines, three television sets, and $4,000 of Simpson’s own money, they began what they thought would be a 90-day experiment: From then until election night in November, they would record the ABC, NBC and CBS evening news broadcasts, which usually aired at the same time.

The day Simpson and Grisham started taping, Aug. 5, 1968, was an eventful one. The Republican Convention began, and Ronald Reagan officially announced his candidacy for the presidential nomination, joining with liberal Republican Nelson Rockefeller in an attempt to stop Richard Nixon’s hopes of a first-ballot nomination.

The news broadcasts also included the era’s biggest stories: fighting in Vietnam, communist leaders meeting in Eastern Europe, and the civil war in Nigeria. Other reports from that day sound hauntingly familiar: an Israeli strike into Jordan and a violent incident at the Korean Demilitarized Zone, in which an American soldier and a North Korean soldier were killed.

Such was the modest beginning of what Rutgers University historian David Greenberg has called the “preeminent video resource for scholars of TV news.”

Although legal and copyright issues continue to hinder access, the Vanderbilt Television News Archive—a repository of television news recordings from the past 50 years—is a national archival treasure.

But the archive’s beginnings are rooted in the political and cultural conflicts of the late 1960s. Simpson, the archive’s founder, first financial backer and chief fundraiser, was deeply conservative. And he was convinced that the network news broadcasts, with their executive producers living in New York’s “liberal atmosphere,” were contributing to social turmoil and unrest throughout the country.

For this reason, he sought to save the recordings for posterity—to be able to show, years later, that CBS, NBC and ABC were as much a part of the problem as the antiwar movement, drug culture and free love.

THE MOST TRUSTED MEN?

Although he later downplayed political motivations in a 1985 C-SPAN interview, Simpson had long been passionate in his concern about television’s malign influence over “the American mind.”

In 1964 he wrote to CBS to complain about Walter Cronkite’s coverage of the Goldwater campaign. He wasn’t necessarily wrong: Cronkite, who enjoyed his reputation as the “most trusted man” in America, did detest Goldwater and was liberal in his politics.

Simpson also believed that television news unfairly blamed President John F. Kennedy’s assassination on the “conservative atmosphere” in Dallas, and he recalled with particular disgust a 1967 network interview with psychologist Timothy Leary, who was encouraging young people to try LSD.

On a business trip to New York in March 1968, Simpson toured each of the three networks. At each stop, he asked to see a broadcast from the previous month. They all told him that they weren’t available—they saved their broadcasts only for about two weeks because

it was too expensive to preserve them.

Simpson was shocked. He viewed nightly newscasts as the equivalent of America’s national newspaper. How could they be held accountable if no record existed of their stories, segments and analyses?

When he returned to Nashville, Simpson found an ally in Vanderbilt librarian Frank Grisham.

Grisham didn’t share Simpson’s politics but did believe that the broadcasts should be preserved. The two took the idea to Vanderbilt’s chancellor, Alexander Heard, a political scientist whom historian Paul Conkin described as a true believer in “an open society, one in which divergent views could find expression” and compete for public acceptance. Heard got the board of trustees to approve a short-term experiment, hoping that the Library of Congress might eventually take it over.

PRESERVING BIAS FOR POSTERITY

The expensive project might have ended after its three-month test run were it not for the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, held a few weeks after the Republican gathering.

On Aug. 28, 1968, the night Hubert Humphrey was nominated, the news networks aired footage of the swelling crowds of protesters, the outbreak of violence in the streets, and the demonstrators shouting “The whole world is watching” as the police attacked them. It was dramatic stuff—and Simpson and Grisham preserved it all.

Although the protesters believed media coverage would create sympathy for their cause, a substantial majority of Americans—including Paul Simpson—sided with the police. When editing the tapes, Simpson realized that NBC had shown the same arrest of one violent protester from three different angles without acknowledging that it was the same person. In Simpson’s view this exaggerated the scale of violence and discredited the police.

In the heated atmosphere of 1968, it was enough to fuel suspicions of media bias. Simpson now had his smoking gun—and a potent fundraising tool.

During the next two years, the tape of the Chicago violence played a critical role in the survival of the archive. Simpson argued that the only way to be able to study the media’s impact was to ensure copies existed for critics, researchers and academics to review. Two conservative Nashville business executives, one of whom sat on the Vanderbilt Board of Trust, made substantial donations to keep the archive functioning.

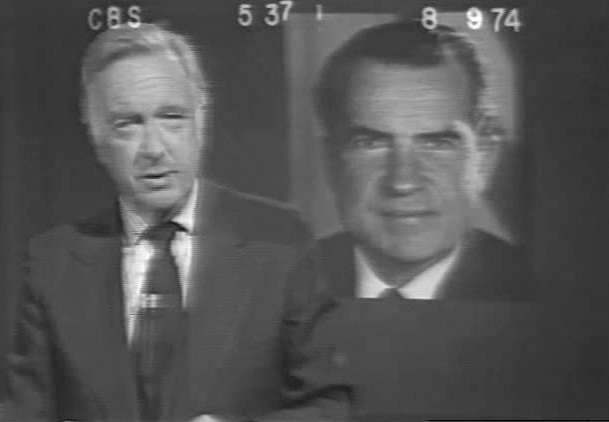

Nixon’s election made the White House receptive to the project. Simpson sent the tape to Patrick Buchanan, a Nixon speechwriter who shared the president’s deep distaste for the media. Buchanan even included a reference to the protest footage in Vice President Spiro Agnew’s famous 1969 speech attacking television news as biased.

“Another network,” Agnew announced, “showed virtually the same scene of violence from three separate angles without making clear it was the same scene.”

THE NETWORKS FIGHT BACK

The networks had never been singled out by elected officials in this way, and they weren’t happy about the scrutiny. Operating as they did with government licenses, they saw Agnew’s speech as intimidation.

With a hubris that, in retrospect, was certain to invite further scrutiny, the three networks pushed back, arguing that they were objective and impartial watchdogs looking out for the public interest. They saw themselves as above politics. As media historian Charles L. Ponce de Leon wrote in 2015, “It was news from Olympus, presented in a tone that suggested the voice of God.”

NBC’s Reuven Frank sarcastically dismissed Simpson’s claim that he was acting in the “spirit of free inquiry,” remarking that “I have never known a self-proclaimed objective student who sought to evaluate my performance because he thought I was doing great.”

The networks also worried that if Vanderbilt continued recording their broadcasts, they would lose the ability to repackage and resell their footage. People could just go to Vanderbilt for it.

CBS accused the Vanderbilt Television News Archive of violating its copyright and sued in December 1973. Amazingly, CBS stated it would destroy the Vanderbilt tapes if it won in court.

Thankfully, Tennessee Sen. Howard Baker helped insert a clause in the revision of the copyright law that protected the right of libraries to record the news. CBS dropped its lawsuit, but some of the restrictions it insisted upon were put in place.

While the entire collection was digitized in the early 2000s, the Vanderbilt Television News Archive is allowed to stream only NBC and CNN to researchers. Examining ABC, CBS or Fox segments requires a trip to Nashville.

The recording of the evening newscasts of the big three networks—ABC, CBS and NBC—continues to this day. In 1995 the archive began recording an hour a day of CNN, and in 2004 an hour of Fox. Through the years the archive has been used by researchers to study topics as diffuse as political bias, gender stereotyping, and even the evolution of television advertising, since the commercials during the news broadcasts are also recorded. The archive was used in the 2015 documentary Best of Enemies because it contained lost footage of the debate between conservative commentator William F. Buckley Jr. and liberal writer Gore Vidal. More poignantly, the archive was used by the mother of an American soldier who died in Vietnam; after someone told her that her wounded son had been photographed lying on the ground during a network news segment, she traveled to Nashville to review archive footage and confirm the account.

Even if one believes Simpson’s perception of deliberate political bias was misguided, his insistence on preserving the evening news in order to study and analyze its presentation was an extraordinarily important contribution.

The British writer Christopher Hitchens once remarked that political partisanship makes us stupid. But in the case of the Vanderbilt Television News Archive, partisanship led to unintended, historically enriching results.

This article was originally published on The Conversation on July 26, 2018.

Thomas Alan Schwartz is professor of history, professor of political science, and professor of European studies in the College of Arts and Science.