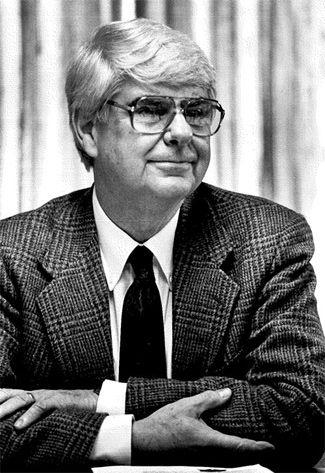

The Rev. Beverly Allen Asbury, who worked tirelessly as Vanderbilt University’s first chaplain to eliminate racial- and religious-based hatred and to promote inclusion and respect for others, died Aug. 22 in Charleston, South Carolina.

Asbury, 89, had become chaplain emeritus at Vanderbilt in 1996. During his 30-year tenure, Asbury launched what has become the longest continuous Holocaust lecture series at any American university. This academic year marks the 41st in which the continuing significance of the Holocaust is explored through lecture, music, film and conversation with leading scholars, artists and survivors from around the world.

He also transformed the Divinity School’s Martin Luther King Jr. Commemorative Series into a campus-wide celebration. Asbury had met King when both were teenagers attending a conference in Atlanta about how to create an integrated student Christian group in the South. Asbury’s passion for civil rights drew him to the ministry.

“Bev was instrumental in shepherding a conservative institution through the radical changes of the 1960s, and, as a person of conscience, was a seeker of social justice,” said Steve Caldwell, a retired student life administrator who came to Vanderbilt in 1969 as a Divinity student. “In a very real way, he was the conscience of the university.”

Caldwell remembers that Asbury, who was also an adjunct Divinity School professor and lecturer in religious studies, was one of his favorite professors.

Asbury was born on Feb. 14, 1929, in Elberton, Georgia. He received his undergraduate degree from the University of Georgia before enrolling at Yale Divinity School, where he earned a master of divinity in 1953.

Asbury became an ordained Presbyterian minister and held various appointments in North Carolina, Missouri and Ohio before being hired by then-Vanderbilt Chancellor Alexander Heard in 1966. His first sermon as chaplain, titled “Neither fish nor fowl,” focused on the delicate nature of a position that is neither fully of the academy nor fully of the church.

Asbury later described himself as both an “agnostic Christian” and a “post-Holocaust Christian.” His longstanding concern for diverse groups on campus to feel comfortable during worship led to the creation of the All Faith Chapel on campus. He noted at the time that other schools had been providing interfaith worship facilities for many years.

Andrew Maraniss, author of a biography of Vanderbilt’s Perry Wallace, the first African American basketball player in the Southeastern Conference, said Asbury was a supportive figure during Wallace’s pioneering days. “It was the Rev. Asbury who invited the first wave of black students out to his home for dinner and a conversation about their lives on campus,” Maraniss said. “After hearing their stories, Asbury called Chancellor Heard and set up a meeting for the black students to speak directly to the administration. Wallace led his classmates into that meeting. I know Perry greatly appreciated Asbury’s kindness, friendship and empathy.”

Asbury helped create Project Dialogue, a forum to enhance intellectual engagement outside of the classroom. He launched the Office of Volunteer Activities and supported Alternative Spring Break, a model for student volunteerism. In a 1996 article in the Vanderbilt Register, Asbury said, “In the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, we had hundreds of students involved with volunteer services, and frequently they were involved in ways that challenged the university.”

One of the controversies had to do with Vanderbilt hosting the all-white South African Davis Cup tennis team. Asbury challenged the students to organize a protest demonstration, applying the principles of nonviolence that the King movement had espoused.

Mark Forrester, now university chaplain and director of religious life, first met Asbury during orientation when Forrester was a first-year Divinity School student in 1979. “During a panel discussion, Bev was unflinching in terms of describing the injustices being suffered through the struggle for civil rights, our engagement in the Vietnam War and other serious issues,” Forrester said. “He asked us tough ethical questions about what our various religious traditions were doing to live up to the wisdom of the traditions that we claimed to represent.”

Forrester renewed his friendship with Asbury when Forrester returned to campus as a Methodist-affiliated chaplain. Forrester also would reach out to Asbury from time to time when Forrester became university chaplain six years ago.

Asbury served on the Tennessee State Commission on the Holocaust for six years and also was the liaison for the State of Tennessee to the U.S. Memorial Council on the Holocaust.

Among Asbury’s many honors was the Friendship Award, given by the Jewish Federation in Nashville in recognition of his interfaith work. He also received the Humanitarian Award from the Southern region of Hadassah.

When Asbury retired in 1996, he did not want a traditional retirement celebration. Instead, three forums were held for the community to explore subjects that had been central to his work. Three distinguished friends of Asbury—James Lawson, Will Campbell and John Egerton—led one of the discussions, “Race, Religion and the South.”

He wanted most to be remembered for his work for racial justice, for interfaith understanding and respect, and against acts of totalism and genocide.

“Bev was part of the last great generation of chaplains that truly shaped American education,” Forrester said. “As the current chaplain, I feel like I’m standing on the shoulders of a towering figure in Vanderbilt’s history.”

Asbury is survived by his beloved wife, Vicky Hake Asbury, two daughters, a son, and 10 grandchildren. In addition, he was stepfather to the daughter and son of his beloved wife, to whom he was married for 38 years.