For the first time, researchers have seen how proteins involved in the daily biological clock interact with each other, helping them to further understand a process tied to numerous metabolic and eating disorders, problems with shift work, jet lag and mental health issues.

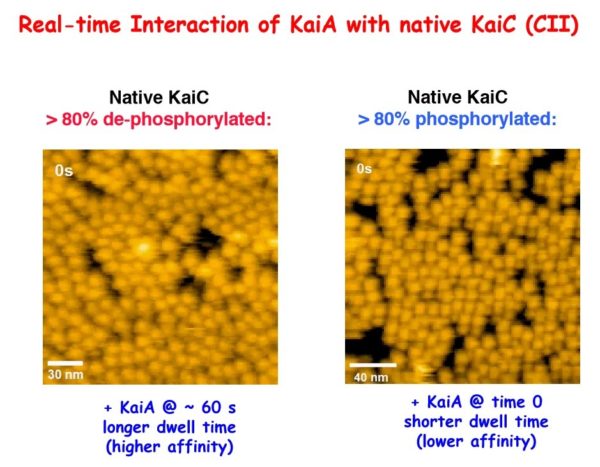

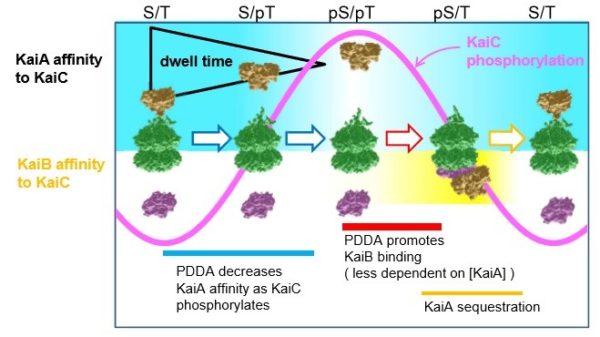

Working with the clock proteins KaiA, KaiB and KaiC from a model system, Carl Johnson, professor of biological sciences, and his team used high-speed atomic force microscopy to visualize the kinetics of the proteins’ interactions. In the presence of adenosine triphosphate — the energy currency of living cells — the proteins rapidly and rhythmically bound to each other, leading to a regulative process called phosphorylation.

Their results, detailed in the article “Revealing circadian mechanisms of integration and resilience by visualizing clock proteins working in real time,” were published Aug. 14 in the journal Nature Communications.

They discovered the on-and-off interactions between KaiA and KaiC take only seconds but combine to create a 24-hour oscillation of phosphorylation in a test tube. This biochemical clockwork keeps the rhythm going over at least 10 days without diminishing.

“We also learned through mathematical modeling that these interactions make the whole system more robust, no matter its environment,” Johnson said. “Perhaps the environment inside cells is changing, but the clock can’t keep accurate time if it changes with the intracellular environment. The high speed interactions between KaiA and KaiC that we observed keeps the oscillation resilient and accurate.”

He said using clock proteins from model organisms allows more rapid progress because the system is relatively simple and therefore easier to see the key interactions.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R37 GM067152, the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science and the Japan Science & Technology Agency/CREST.