By Dr. John Sergent, BA’63, MD’66

In 1972 I moved to New York City with my wife, Carole, BA’63, and our two young daughters to do a fellowship in rheumatology. A few months after we moved, we met Francis Robinson, a fellow Vanderbilt alumnus (BA’32, MA’33) who was then the assistant manager of the Metropolitan Opera and its spokesperson on national TV. I confessed to Francis that I had never seen an opera, and he immediately set about remedying my deficiency.

Francis gave us a personal tour of the Met that included watching the crew paint the huge backdrops for the scenes, seeing the rows of sewing machines where elaborate costumes were being made, and finally hearing Beverly Sills rehearsing for her Met debut in Siege of Corinth. We were blown away, and very soon afterward I managed to see my first opera, La Traviata, which I’ve now seen several times and is still my favorite.

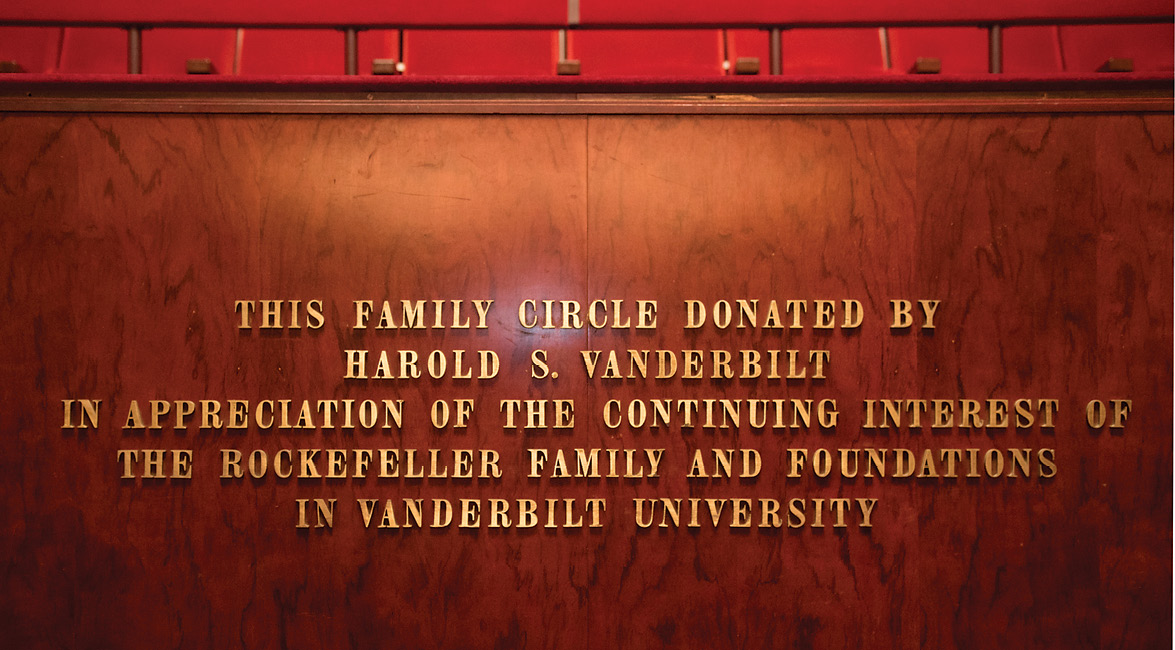

Money was tight in those days, so the only seats at the Met that we could afford were in the Family Circle, the very highest and farthest removed seats—so far that I actually brought field glasses, not opera glasses, to watch the performances. One night, as we were leaving a performance, I noticed the large plaque that is prominently displayed at the front of the Family Circle, which was established by a donation from Harold S. Vanderbilt. The inscription thanks the Rockefeller family for its generous support of Vanderbilt University. Seeing this plaque again at the Met last year reminded me of its interesting backstory, particularly because that story involves the creation of Vanderbilt’s School of Medicine and the Vanderbilt University Medical Center as we know them today.

Lincoln Center was the brainchild of the Rockefeller family, which gave a large portion of the money to build it. The connection between the Rockefeller family and Vanderbilt University, as noted in this magazine a decade ago, begins in 1902. That’s when John D. Rockefeller started the General Education Board, one of whose stated purposes included improving undergraduate and medical education in the South. In 1917 Wallace Buttrick became president of the General Education Board.

Buttrick was a good friend of Vanderbilt Chancellor James H. Kirkland and had already been involved with relocating Peabody College next to Vanderbilt. General Education Board funds also helped build what was then called the Social-Religious Building at Peabody, now named the Faye and Joe B. Wyatt Center.

However, the largest contribution was still to come.

In 1920, G. Canby Robinson, the dean of the Washington University School of Medicine, was recruited to come to Vanderbilt as dean. The medical school was then located downtown on property previously owned by the University of Nashville, and its buildings were in need of many improvements.

Around the same time as Robinson’s recruitment to Vanderbilt, Buttrick had been influenced by one of his close friends, Abraham Flexner, head of a school for boys in Louisville, Kentucky, who had written a book decrying the state of American higher education. That book was followed by the Flexner Report, a comprehensive survey of all U.S. and Canadian medical schools, which resulted in the closure of more than half the medical schools in the country. Flexner was convinced that Vanderbilt was the school in this region best suited to become the top-quality university he envisioned. It was Flexner, in fact, who convinced Canby Robinson that if he moved to Nashville, great things could happen.

And they did. The estimates on the cost of repairing the downtown medical facilities totaled $4 million. But Robinson, with Flexner’s help, persuaded Buttrick and the General Education Board to spend a little more, $4.5 million (the equivalent of about $58 million today) to build a medical school on the main Vanderbilt campus that would be like none other in the country—a single facility to house a hospital, a medical school and research facilities. It was the largest expense the General Education Board had ever approved, and by 1925 the new Vanderbilt Medical Center, now known as Medical Center North, opened its doors.

The General Education Board eventually became the Rockefeller Foundation, and Vanderbilt continued to benefit from its largesse, including millions more to the School of Medicine as well as major gifts to the School of Nursing and the Divinity School.

At the same time Lincoln Center was being built in the late 1950s, Harold S. Vanderbilt, the great-grandson of the university’s founding benefactor Cornelius Vanderbilt, was chairman of Vanderbilt University’s Board of Trust. He was certainly aware of the many contributions the Rockefellers had made to the university and chose to donate the Family Circle at the Met as his sign of appreciation to the Rockefeller family.

And that is how the only public acknowledgement of the Rockefeller–Vanderbilt connection ended up in an unlikely venue: The Metropolitan Opera House in New York City.

And that is how the only public acknowledgement of the Rockefeller–Vanderbilt connection ended up in an unlikely venue: The Metropolitan Opera House in New York City.

Dr. John Sergent is a rheumatologist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and a professor in the School of Medicine.