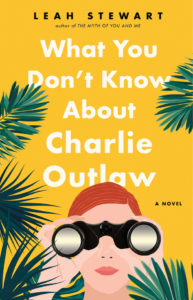

Leah Stewart, BA’94, has five acclaimed books to her credit, and her sixth, What You Don’t Know About Charlie Outlaw (2018, G.P. Putnam’s Sons), released this spring, is certain to further her reputation as a writer of keenly observed, engaging fiction. With its lively story centered on a pair of actors in a troubled relationship, Charlie Outlaw might be described as an action-packed romantic comedy, but the book is no mindless romp. Early reviews from Kirkus and Publishers Weekly use words like “thoughtful,” “satisfying” and “endearing” to describe it, and one offers praise for the “unstudied lyricism” of Stewart’s prose.

Stewart traces her path as a fiction writer back to Vanderbilt, where a nascent interest in writing motivated her to sign on with the Vanderbilt Hustler in her freshman year. She’d always been a serious reader with the impulse to write, but “I didn’t realize there were living writers producing what we call literary fiction. I thought the practical thing to do with an interest in writing was to be a journalist.”

An editorship at the Hustler and summers spent interning at The Tennessean in Nashville and The Commercial Appeal in Memphis left Stewart disenchanted with journalism. “I did not like talking to strangers,” she says. Novelist A. Manette Ansay (Vinegar Hill, Good Things I Wish You), who arrived at Vanderbilt as an assistant professor in Stewart’s senior year, encouraged her to pursue an M.F.A. in creative writing. “For the first time,” Stewart says, “a career as a fiction writer came to seem like a viable option.”

These days Stewart juggles work on her novels with family responsibilities and her job as a professor at the University of Cincinnati, where she heads the Department of English. She tries to make a habit of writing one day a week during the semester “to keep my subconscious in touch with the work,” and she relies on periodic writing retreats to get the bulk of a novel done.

That’s how she wrote Charlie Outlaw, which, unlike her earlier books, is told through an omniscient narrator. “The omniscient point of view gives a strong sense of how everyone is connected,” says Stewart, making it a good choice for a story that explores the burdens of celebrity. “Omniscience is a way of writing about community, and celebrity is communal.”

That’s how she wrote Charlie Outlaw, which, unlike her earlier books, is told through an omniscient narrator. “The omniscient point of view gives a strong sense of how everyone is connected,” says Stewart, making it a good choice for a story that explores the burdens of celebrity. “Omniscience is a way of writing about community, and celebrity is communal.”

Stewart points out that the problems of fame are no longer confined to a relative few. In the age of social media, “any of us can gain a certain amount of celebrity at any time,” she says. Questions of public identity and popular opinion are certainly pertinent to novelists, as she wryly notes.

“I often joke,” she says, “that I’m going to give my children a little sheet so they can give me a star rating.”

—Maria Browning