Steve Turner (BA‘69) was a student of cities long before Nashville became a hip place to visit as well as live.

He and his wife Judy envied the European lifestyle where city residents worked at their street-level shops or businesses and lived upstairs. That historic model, born of convenience if not necessity, created vibrant urban cores and walkable communities.

They wanted to live like that and thought Nashville could be like that. But in 1992, when the Turners bought a near-derelict 100-year-old brick building on Second Avenue just off Broadway, zoning codes did not allow for “mixed use” in Music City’s downtown.

The times, and Nashville, have changed exponentially. And Turner, through MarketStreet Enterprises, his real estate development company, has had a front-row seat to Nashville’s transformation and been an important driver in much of it.

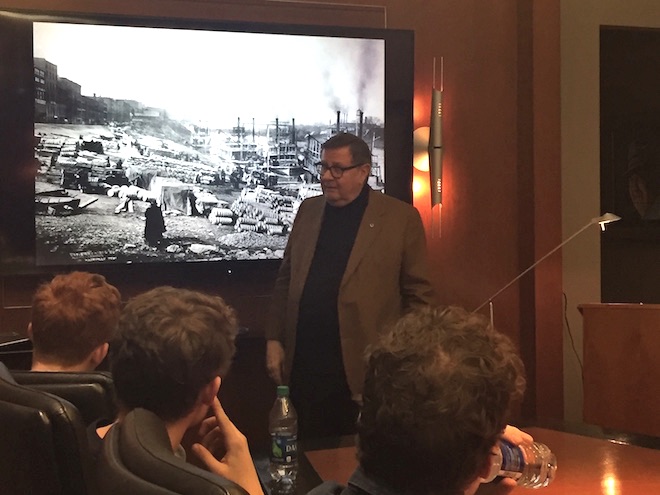

Turner, an emeritus member of Vanderbilt University Board of Trust, shared his experience, vision and excitement with a group of first-year undergraduates during a recent class visit to that old, five-story brick building.

The students are enrolled in Triumph of the City, an iSeminar led by Christopher Rowe, professor of the practice of engineering management and director of the Division of General Engineering. The class is exploring the evolution of communities from agriculture to manufacturing to knowledge work; population density; infrastructure; socioeconomic mobility; health and sanitation; engineering and technology; and what the future of cities might look like.

“I am a student of cities myself,” Turner told the students. “I am fascinated by their impact on society. A city shouldn’t be a donut with a hole. A city should be a Danish with all the good stuff in the middle.”

That was not the state of affairs in 1992 Nashville. “Downtown was not a place where a lot of people hung out,” Rowe said, giving the students some context.

Multiple factors fueled Nashville’s renaissance, Turner said, citing willing public officials, public-private partnerships, and mutual respect and creativity among collaborators.

Public-private partnerships gave downtown now-familiar destinations and significant architectural landmarks. Among them: The Country Music Hall of Fame, The Frist Center for the Visual Arts, The Schermerhorn Symphony Hall, and the Music City Center.

Turner and his company had also been acquiring huge chunks of property in The Gulch, which was a blighted wasteland of old railroad tracks and deteriorating warehouses. In 1997, Turner said, property in The Gulch was assessed at $8.1 million and generated a scant $100,000 in property taxes.

Today, Gulch area property is assessed at $600 million and generates more than $7 million in taxes. The difference?

Thoughtfully planned mixed-use development with MarketStreet Enterprises leading the way: 1700 residences, 700,000 square feet of Class A office space, and 70 restaurants and shops. It was the first LEED-certified neighborhood in the Southeast and shows what great investments can be made in cities when they are done responsibly, Turner said.

The students’ visit included a tour of 138 2nd Ave., starting in the basement, with its vestiges of rails that took carts back and forth to the riverfront and wall markings where horse and donkey shoes hung. The history of the building as well as Nashville fit well in the seminar’s curriculum, which includes the reasons cities decline or fail, the Rust Belt, pandemics and population, implications of policy, and NIMBY phenomenon – Not In My Backyard.

The seminar was open to first-year students in all majors; five of the 15 students enrolled are outside the School of Engineering. Among declared engineering majors, civil engineering students represented the largest concentration.

The idea, Rowe said, is to give students potential immersion topics for future study and prepare them to pursue their passions through rigorous, compelling, and unique projects.

Having students hear from Turner personally was a natural fit, Rowe said.

“Meeting alumni, especially influential alumni, is critical for our undergraduates,” he said. “Mr. Turner is one of the most significant change agents for the city of Nashville. I thought it was important for the students to meet him to gain the affinity for the city he has and to bear witness to the many important projects with which he’s been involved.”

The students loved it. Several said the visit was their favorite part of the seminar. It would have been great, they said, to have more time and accompany Turner on a walking tour of the city to hear his observations about specific projects and areas and how they were developed.

Turner also is an active philanthropist and Vanderbilt benefactor. His father, Cal Turner, started retailer Dollar General, where Steve Turner worked until the late 1980s. He and Judy then set their sights on Nashville and that derelict building.

“First, we had to put a roof on it,” Turner said. The former mercantile center then was divided into two structures to incorporate large windows for natural light and create a public walkway to the riverfront.

The building neatly encapsulates the city’s history but the Civic Design Center, a nonprofit organization housed on the ground floor, looks to Nashville’s future. Students met with the center’s staff, including Chief Executive Officer Gary Gaston (M.Ed.’16) and learned about ongoing projects to make the city more livable.

The center works with public agencies and private partners on innovative designs to make neighborhoods more walkable, create more functional public spaces, add green spaces, and improve access to transit, among other initiatives. Increasing public participation in shaping Nashville’s future is an overarching goal – and one that Turner embraces.

Plus, he can easily brainstorm with center staff because he has a private office upstairs. That rejuvenated brick building certainly has mixed uses. The Nashville Civic Design Center is at street level. The Turner Family Office, which includes staff for multiple foundations as well as asset management, is on the second floor.

And Steve and Judy Turner live on the top two floors.

Media Inquiries:

Pamela Coyle, (615) 343-5495

Pam.Coyle@Vanderbilt.edu

Twitter @VUEngineering