By Jennifer Plant Johnston

“On the city’s western border, reared against the sky,

Proudly stands our Alma Mater as the years roll by.”

—opening lines of the Vanderbilt Alma Mater

When Poppy Hicks Clements, BA’86, moved into Hemingway Hall as a freshman, she found instant community among her fellow classmates in Kissam Quadrangle, the collection of dormitories that once stood on the corner of West End and 21st avenues.

“Kissam was a very special little haven,” says Clements, who, with husband Rob, is parent to current Vanderbilt students Ross (Class of 2019) and Phoebe (Class of 2021) and graduates Ann, BA’13, and Curry, BA’15. “You could go in your room and be by yourself, or you could open your doors to a world of friends just outside.”

Fast-forward 35 years, and the world that Ross inhabits in Moore College, where Kissam once stood, is vastly different.

“He’s very close to exactly where my room was spatially,” Clements says. “I was very sad to see Kissam come down, but walking in [Moore] and seeing that fabulous spot—it’s amazing.”

As aging residence halls like Kissam come down, they’re being replaced with residential facilities designed to encourage classmates from varying backgrounds to come together in shared communities, living alongside faculty members who help foster dialogue and discovery outside the classroom.

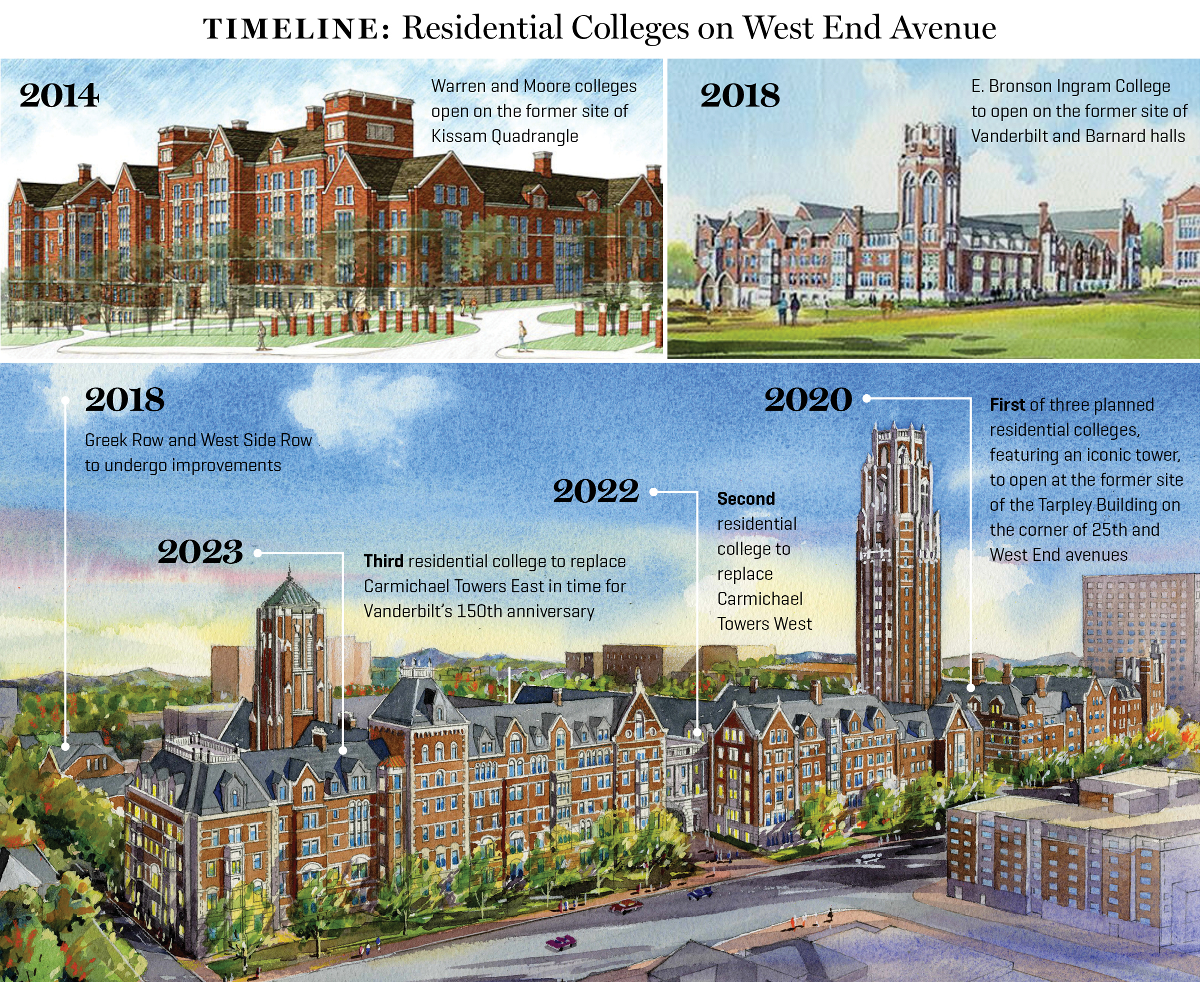

Known as residential colleges, this living–learning concept debuted in 2008 with construction of The Martha Rivers Ingram Commons for first-year students, made up of 10 residence halls on the southeast corner of campus. Building then shifted to West End Avenue, starting with Warren and Moore colleges for upperclass students, which opened in 2014. The latest project, E. Bronson Ingram College, replaces the former Vanderbilt and Barnard halls and is scheduled for completion this summer.

“As much as I loved living in Hemingway,” Clements says, “I would never refer to it as a learning environment, except for learning to make friends.”

Now, the residential colleges initiative is continuing with expansive plans to reimagine the swath of campus that runs along West End Avenue, from Alumni Lawn to 25th Avenue, across from the Barnes & Noble at Vanderbilt bookstore. This area includes Carmichael Towers, Greek Row and West Side Row. The multiphase, $600 million project calls for extensive renovation in the area and the construction of three new residence halls.

As part of the plan, the four aging Carmichael Towers will be demolished, housing on Greek Row will be improved, and much of the street and parking footprint will be reclaimed as green space to connect this “West End Neighborhood” to the main part of campus. All told, the West End Neighborhood project, scheduled for completion in time for Vanderbilt’s 150th anniversary in 2023, will fundamentally reshape the university’s facade along West End Avenue and also fulfill its goal of providing an authentic living–learning environment for all undergraduates.

“Much more than just housing, residential colleges are a physical representation of our vision to educate the whole student and develop leaders who will change the world. They bring together young people of diverse backgrounds with faculty to build communities based on mutual understanding,” says Chancellor Nicholas S. Zeppos. “With timeless architecture that will last for generations, communal dining and creative spaces, every detail is designed to build a lasting community grounded in civility, respect and friendship.”

STRATEGIC INVESTMENT

Vanderbilt belongs to a short list of institutions that have embarked on creating an undergraduate residential experience that encompasses all four years of a student’s time on campus. Although the model of incorporating learning into residential life stretches back centuries, with roots at Oxford and Cambridge in Great Britain, Vanderbilt’s version is very much forward-looking.

“Residential colleges are the right step for Vanderbilt at the right time,” says Steven Madden, BS’91, CEO of the Houston-based Apex Heritage Group and a member of the university’s Board of Trust. He says the move dovetails with Vanderbilt’s commitment to eliminate loans from financial aid packages as part of the decade-old Opportunity Vanderbilt program.

“We have this hugely diverse, talented campus. Bringing students together in residential colleges across the four-year experience here builds on our sense of community,” Madden says. “Residential colleges allow our students to live and learn alongside one another, not just inside the classroom, and to take full advantage of the community here to grow as individuals and become leaders. ‘Iron sharpens iron,’ and the more time our students can collaborate together, the better education Vanderbilt can deliver.”

The preliminary phase of the West End Neighborhood project got underway in December 2017 with efforts to bury utility equipment and prepare the site at the corner of 25th Avenue South and West End to begin construction on a striking iconic tower. This as-yet-unnamed residential college will transform the area, where the Tarpley Building for many years housed enterprises as varied as a funeral parlor and the Office of the University Chaplain and Religious Life. Scheduled for completion in August 2020, it will feature two interior courtyards, dance studios, an art gallery, a library, great rooms, dining options, and an apartment for visiting scholars, and will continue the residential colleges tradition of faculty living among undergraduates.

The project also calls for five houses in the Greek Row area to be torn down and replaced with six new houses—the first major improvements since the area was established in the 1960s. The Panhellenic House, home to many of the university’s historically black sororities and fraternities, will have a more welcoming central location, and a new multicultural house will be added. Meanwhile, the historic West Side Row area, where the university’s first student apartments were built in 1886, will continue to be preserved and beautified.

Once the residential college at the corner is complete, Carmichael Towers will be demolished to make way for a second residential college, scheduled to open in August 2022, and a third, in August 2023, just in time for the university’s 150th anniversary.

While the project is the result of a well-planned architectural vision, it is also driven, inspired and shaped by giving, says trustee Mark Mays, BA’85. Simply put, residential colleges would not be a reality without the continued support of the Vanderbilt community.

“Our community of support was hugely important in the past phases of residential colleges, and will be a driver in this next phase as well,” says Mays, who is CEO of Rocking M Capital in San Antonio. “Supporters of this project understand how it aligns with the educational philosophy here and how it encourages learning outside the classroom.”

NEW FRONT DOOR

Much like their sister halls, the new residential complexes in the West End Neighborhood will be of extremely high quality, built to last, and designed to foster interaction. And particular attention will be paid to how these buildings relate architecturally to others on campus.

“The architectural decisions we’ve made are the result of many detailed conversations and studies about different variations within the Collegiate Gothic language, but with details—from colors of brick to selections of stone—to match and pay tribute to existing buildings, both on and off campus,” says Eric Kopstain, vice chancellor for administration.

The Collegiate Gothic style was first introduced at Vanderbilt when the university decided to move the School of Medicine to the central campus. Designed by Henry R. Shepley, the “new” VUSM building opened in 1925. Alumni Memorial Hall and Neely Auditorium were the next two built in Collegiate Gothic style, followed by Buttrick, Calhoun, Garland and old Wesley Hall, which burned in 1932 and left a vacant lot that is now Library Lawn. The demolition of the original Kissam Hall made way for Alumni Lawn.

Until the residential colleges endeavor began this century, Vanderbilt and Barnard halls, which opened in 1952, were the last Collegiate Gothic buildings to be built on the central campus, according to The Vanderbilt Campus: A Pictorial History (1978, Vanderbilt University Press) by the late Robert A. McGaw, ’35, the university’s former historian and secretary.

Opened in 1966 and 1970, the four Carmichael Towers were built to accommodate an influx of baby boomers during that era. The towers house 1,200 students in total, but their vertical, midcentury style makes them appear incongruous at best—and at worst downright unattractive, some might say—next to other buildings on campus.

“The towers are efficient but not very pleasant to look at,” says University Architect Keith Loiseau.

Once Carmichael Towers are replaced with new residential colleges, Vanderbilt’s facade along West End Avenue will be complete, creating a more welcoming entryway to campus for visitors while also enhancing security and privacy for those within. It also will mark the culmination of a decades-long project to shift the university’s entrance from the original one off 21st Avenue South, near what is now Vanderbilt Law School, toward West End.

“Building residential colleges has provided an opportunity to redefine a new front door for the university while the large block buildings also create a buffer to student activities within campus, helping to maintain the quality of life on the interior,” Loiseau says.

Screening the interior of campus from the noise and commotion of the city pays tribute to architect Edward Durell Stone’s 1940 campus master plan, which embraced the concept of the university as an oasis in the middle of the city, free from vehicular circulation. Through the years, the addition of hundreds of parking spots, along with above-ground electricals and cut-through roads, has made the West End Neighborhood part of campus feel disconnected from the rest. The new residential colleges will correct that.

“With the value of land in that district, do we really want to devote that much land to parking cars?” asks Bob Grummon, an architect in the university’s Office of Campus Planning and Construction. “We want to return the area to the students.”

Service lanes will remain for emergency vehicles, and an ongoing transportation study will continue to address vehicular accessibility, taking into consideration the multimodal approaches now available, such as on-demand car services, bike shares, public transportation and campus shuttles.

Robert Waits, the university’s landscape architect, looks forward to the planned expansion of green spaces, aided in part by removing roads and parking spaces.

“This is one of our first swipes at expanding the arboretum and transitioning to a more pedestrian-friendly community, which hits on many of the guiding principles devised as part of the FutureVU process,” he says, referring to the university’s comprehensive campus land-use plan launched in November 2015.

LEADERS OF TOMORROW

Built into the entire West End Neighborhood planning process has been extensive input from impacted organizations, including student organizations along Greek Row. “Our students have really progressive attitudes. They are changing Greek organizations from within and want them to be better integrated and welcoming to all,” Kopstain says. “We’re investing in the future of the university community by beautifying the space where student organizations reside.”

Residential colleges offer students opportunities not only to cultivate individual interests but to share those interests with others as well. For instance, Poppy Clements’ son Ross, who plays gigs with his band in the Nashville area, makes use of the practice rooms at Moore and plays the piano in the lobby to relax. He also is steps away from the Vanderbilt recording studio, which he helps run.

Meanwhile, the youngest Clements, Phoebe, lives in West House on The Ingram Commons. “She hasn’t missed a beat,” Poppy says. “She’s taken advantage of everything. They’ve done such a good job of offering interesting clubs and activities that she’s been exploring.”

Her other two children also experienced The Ingram Commons. Daughter Ann lived in Hank Ingram House, while Curry was in North House.

Faculty interactions, inside and out of the classroom, have been a highlight for both generations of Clementses. A favorite teacher of Poppy’s, Professor of English Roy Gottfried—“the quintessential professor with his pipe and his jacket with patches on the elbows,” she says—also taught her daughter Ann. Leonard Folgarait, Distinguished Professor of History of Art, is another favorite, who served as Poppy’s academic adviser and taught her son Ross.

“All those teachers even then were so extraordinary and excited to be there and share their knowledge,” Poppy says. “Anything you can do to make that an important piece of your education, I’m all for it.”

Those who provide support to the next phase of the residential colleges experience “understand that its impact is not limited to Vanderbilt’s campus,” says trustee Mays. “Residential colleges offer environments that encourage students to grow into leaders who make differences in their communities near and far.”

But it’s not just current or soon-to-be students who will benefit from the “big and bold” residential colleges initiative, Zeppos says.

“We are choosing to make this investment for our current generation and for the generations of Vanderbilt students yet to come,” he says. “These buildings are being built to inspire, to create community, to generate knowledge—and they are built to last.”

Jennifer Plant Johnston is a Nashville-based freelance writer with more than 30 years of experience, many of them writing for Vanderbilt. A journalism graduate of the University of Tennessee and a former Associated Press reporter, the Oak Ridge, Tennessee, native was executive director of the Vanderbilt Center for Nashville Studies before retiring in 2016 to travel and write.

See photos of residential life, then and now, on campus: