If you’ve read Margot Lee Shetterly’s New York Times bestseller Hidden Figures or watched the Oscar-nominated film adaptation of the same name, you’ve probably asked yourself, “Why haven’t I heard this story before?” You’re not alone.

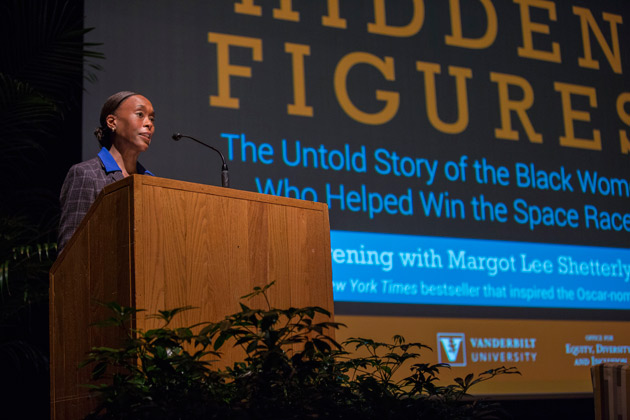

In the nearly year and a half since Shetterly published her book, which chronicles the little-known history of African American women mathematicians and engineers at NASA during the mid-20th century, that’s the question she is asked most often. The author spoke in Sarratt Cinema Feb. 20 as part of an event sponsored by the Office for Equity, Diversity and Inclusion and the office of Vice Provost for Inclusive Excellence Melissa Thomas-Hunt.

“People frequently ask that question as if not knowing the story somehow implies a personal failure on their part,” Shetterly said. Yet despite growing up in Hampton, Virginia, the daughter of a career research scientist at the NASA Langley Research Center, Shetterly didn’t know the story until she began researching her book in 2010.

“My father went to college with one of (aerospace engineer) Mary Jackson’s nieces. But before he was hired at NASA, he had never heard of the black women who were working there or anything about the work that they were doing,” Shetterly said.

“When he arrived at that campus in 1964 for his first day of work, Dorothy Vaughan had already been on the job for two decades,” she said. “Mary Jackson and Katherine Johnson each had been there for more than 10 years.” These women and countless others worked as human computers and helped calculate the trajectories, launch windows and emergency back-up return paths for Project Mercury, the United States’ first human spaceflight program; the 1969 Apollo 11 mission to the moon; and more.

Shetterly said the emotions that accompany the “Why didn’t I know?” question range from elation to frustration. “I hear that elation when it’s asked by a girl or young woman who is passionate about science or math or engineering and finally feels that she has found her people,” she said. “I also hear it asked with anger and with sadness, particularly from older people of color or from women who are fighting their way up through the sciences—especially the women from that generation who became teachers or who wanted to become engineers and didn’t find that pathway and didn’t know that they were part of this invisible sisterhood.

“Why has it taken us so long to tell these stories, and why didn’t we turn Dorothy Vaughan, Mary Jackson, Katherine Johnson and Christine Darden into role models and use them to pull generations of young people, particularly young women, into science careers?” she said.

The answer to this question is complex, Shetterly said. The work these women did was classified, and they performed their jobs dutifully and without expectation of fanfare. More significantly, the black women were physically segregated from their white counterparts, and the work of women as a whole was valued less than that of their male peers, rendering them even less visible.

“I don’t know that there is any perfect or pat answer to the question, but the more time I spend trying to answer it, the more I’ve come to believe that there is another question that is ultimately more meaningful when it comes to stories like this,” Shetterly said. “And that is: What else have we missed?”

For Shetterly, the lack of documented stories like the ones depicted in her book during her childhood and adolescence created an avoidance of history, despite growing up with these women in her community.

“My textbooks would offer cursory information about the state of blacks in America, but they offered virtually nothing about black Americans as individuals and as communities, who I knew firsthand were as engaged in the pursuit of life, liberty and happiness as any other group of citizens in our country,” she said.

“What I wanted to know was, where were the black protagonists? I could never square the textbooks’ narrow and degrading presentation of the past with my particular present, and certainly had problems attaching the past to my future.” In college, Shetterly majored in finance and avoided history classes “like the plague,” she said.

“The absence of fully realized portraits of people who pushed our country to live up to its founding ideals—not despite their history but because of their history—has created a powerful vacuum,” said Shetterly, who was inspired to pen Hidden Figures, her first foray into book writing, to help fill this void.

“America is about the lives and the beliefs and the stories of every single person in this country, no matter where they came from or how or when they got here,” she said.

“Hidden Figures naturally has particular resonance for people who are black or female or scientists, or all three, but this history is ours—it is all of ours—and in a time when our country can seem fractured beyond repair, the power of story is such that it is still possible for people who believe themselves to be incompatibly different to see some things the same way.”

“By telling this story, Ms. Shetterly has shined a light on critical figures in our nation’s history and inspired countless new future scientists, researchers, scholars and leaders,” Thomas-Hunt said in her introduction of the author. “The success of Hidden Figures is a testament to Ms. Shetterly’s outstanding research, commitment and talent and also speaks to the tremendous appetite in our country for more of these untold stories. By telling the story so well, Hidden Figures has opened doors that have been closed for far too long.”

“Telling stories is a way to connect across differences and bring people together,” said Tina Smith, interim vice chancellor for Equity, Diversity and Inclusion. “Yearlong planning and collaboration among our office, the Office for Inclusive Excellence, the Graduate School, the dean of students and The Martha Rivers Ingram Commons resulted in an event enjoyed by undergraduate and graduate students, faculty and staff—different individuals from different spaces across the Vanderbilt campus.”