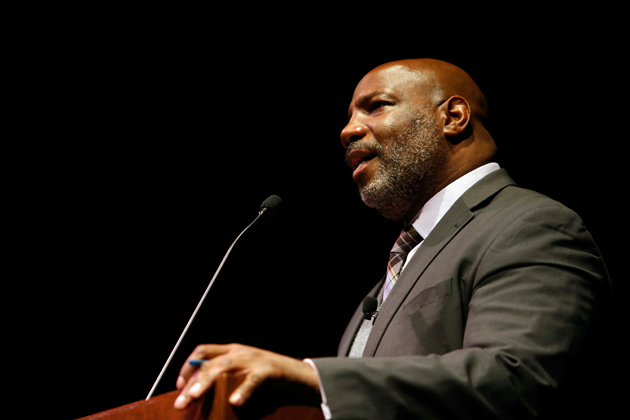

Jelani Cobb, a Columbia University professor who has written extensively on race and injustice, spoke at Vanderbilt Jan. 17 on the deep significance of Martin Luther King Jr.’s legacy for those seeking to understand and respond to recent divisive political developments.

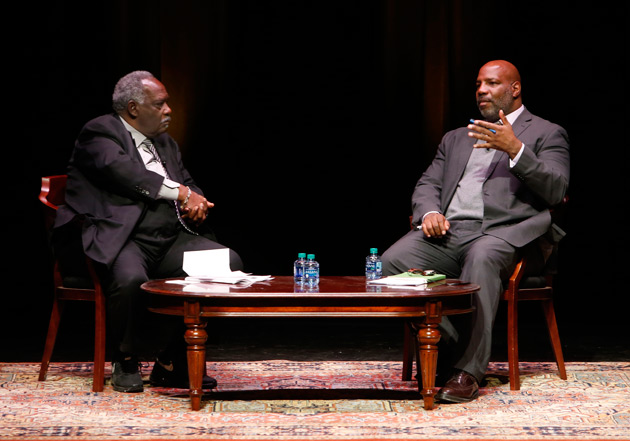

Cobb, the Ira A. Lipman Professor of Journalism at Columbia University and a staff writer for The New Yorker magazine, delivered the keynote address at an event at Langford Auditorium titled “From Louis Armstrong to the NFL: Racial Protest in America.” He was introduced by David Williams, vice chancellor for athletics and university affairs and athletics director, who also moderated a question-and-answer session following the talk.

This was the third event in the Chancellor’s Lecture Series for 2017-18. Cobb’s lecture was also part of Vanderbilt’s 2018 Martin Luther King Jr. Commemorative Series.

Cobb first addressed President Trump’s reported inflammatory comments about Haiti and Africa during a meeting last week with a bipartisan group of senators on immigration policy.

“I was struck by the fact that so many Americans do not realize how indebted the United States was to Haiti during our nation’s early history,” he said.

Cobb cited then-President Thomas Jefferson’s 1803 Louisiana Purchase deal with France, which doubled the territory of the United States for only $15 million. “What many have forgotten is that Napoleon was motivated to make this deal because of the catastrophic damage to the French economy that the Haitian Revolution had reaped,” Cobb said. “When the Haitian slave revolt began, it had such disastrous implications that Napoleon agreed to give Jefferson a deal of a lifetime.”

Cobb provided historical insights on several momentum shifts through the years for the U.S. civil rights movement. “The movement had—in an incredibly short period of time—achieved a tremendous amount of change between 1955 and 1965, but by 1966 a different dynamic was underway,” he said. “In 1967, King had come to a crossroads in terms of what had been achieved during his time with the movement. He went to Jamaica to think and reflect on where the movement might go.”

One reason for the growing political backlash against King was his continued opposition to the Vietnam War. Indicators of the backlash included George Wallace’s run for the presidency as an avowed segregationist, and the Republican Party’s “Southern strategy” to attract white voters to Richard Nixon.

King wrote Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community? during his time in Jamaica. “Dr. King was talking about this backlash even as it was coming into fruition,” Cobb said. “He knew that this dynamic was not new, and I suspect that we are actually living in one of these times of backlash right now. A great deal of what we have seen in American society can best be understood by what Dr. King was explaining.”

Cobb noted in conclusion, “King left us the heroic example of the kind of faith and optimism that is necessary to create significant change. The saying ‘we shall overcome’ is not simply a slogan, but an accurate forecast of the future we are helping to create.”

Williams opened the Q-and-A by asking Cobb to comment on a recent statement by Harry Edwards, a noted sociologist and civil rights activist, that “ … we need to stop thinking about the original sin of America as being slavery and recognizing that the original sin of America is white supremacy, and until that is dealt with, we will continue to have the same problems.”

Cobb responded: “ … The ability to create slavery was a product of the ideology of white supremacy, but at the same time, the economics that incentivized slavery were reinforced by the doctrine of white supremacy. There’s a kind of mutual and perpetual reinforcement between those two concepts.”

A student asked Cobb whether there’s a double standard for those who say they support King’s legacy, but oppose athletes taking a knee during the national anthem to protest racial injustice. Cobb agreed, offering the example of King, who was willing to give up popularity to maintain his principles.

“King was thought of as ‘dangerous’ by a lot of white people and too moderate by many black people. But he was not willing to sacrifice moral authority for transactional politics,” Cobb said.