As the chairmen of the first five Impact symposia, we are delighted when articles about this important and unique Vanderbilt institution are published, most recently the “Speak Up” article written by Andrew Maraniss in the Spring 2017 Vanderbilt Magazine.

Successive generations of Vanderbilt students and alumni should understand the contributions of Impact to the Vanderbilt and Nashville community for more than 50 years—the period when Vanderbilt has become a major national university. We appreciate that Mr. Maraniss, an award-winning author and distinguished alumnus, chose to shine a spotlight on the significance of Impact ’67 in Vanderbilt history.

This article called attention to Impact as an institution and singled out Impact ’67 as “one of the signature moments in the university’s history.” While correct, we believe the article only partially conveyed why. We have joined together to write this letter based on our firsthand knowledge. It provides a more complete story of Impact’s importance as a Vanderbilt institution since the very first program in 1964 and clarifies key aspects of Impact ’67 and its aftermath.

The inaugural Impact ’64 was electrifying, beginning with the opening Friday night debate before a full Neely Auditorium on the subject of segregation: Richmond News-Leader Editor James Kilpatrick supported segregation, while Atlanta Constitution publisher Ralph McGill opposed it. Even freshmen who knew little about Impact before that night realized they were watching Vanderbilt changing. And the campus was never the same.

Impact ’64, like its successors, was a two-day event. The Saturday program again drew large audiences. It featured James Forman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and other speakers discussing the changing Southern economy. The Commodore termed that weekend “the most outstanding intellectual stimulant administered to the campus within memory.” Impact immediately became a campus institution.

Impact ’65 generated so much interest that its sessions were held in Memorial Gym. Dozens of other colleges and universities sent delegates. It began a tradition of fraternity and sorority houses hosting a luncheon for a speaker. Informal gatherings of speakers and students enhanced the campus dialogue. The first Impact Magazine was published. Segregationist Alabama Gov. George Wallace and Roy Wilkins, head of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, headlined, and reinforced the fact that Impact was again bringing cutting-edge national debate to campus.

Riding the momentum created by two back-to-back successful programs and attention from the escalation of U.S. involvement in Vietnam, Impact ’66 turned its focus to the world at large. Speakers included Sen. Barry Goldwater (the Republican nominee against President Johnson in 1964), former ambassadors Trằn Văn Dĩnh (South Vietnam to the U.S.) and Alexis Johnson (the U.S. to South Vietnam), and Alexander Kerensky, the last premier of Russia before being overthrown by Lenin in the Bolshevik Revolution. With attendance reaching 2,000 in 1966, Impact ’65 and ’66 each had larger attendance than the year before. Impact again dominated campus attention.

From its beginning, Impact was a student responsibility and student-run. A growing number of students wanted to open Vanderbilt to the world beyond the campus. Administrators, particularly Dean Sid Boutwell, gave the idea of a symposium backing in 1963. But the university provided no budget. Impact was given life entirely by students.

Student leaders in 1963–64 committed their time and effort to the risky task of staging an unprecedented campus event. Students had to create an organization, choose a topic, invite speakers, etc. They organized a successful parent fundraising effort to generate startup funding. Widespread student support through ticket sales was essential to financial viability, and tickets provided the lion’s share of revenues in the early years.

Significance of Impact ’67

The enthusiasm of students was matched by the vision and steadfast support of Chancellor Alexander Heard. From early on, Heard had regular meetings with Impact leaders. In 1966–67, Bob Eager met with him one-on-one throughout the year, and Heard was informed before invitations were sent to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Stokely Carmichael (then the new “Black Power” head of SNCC), and beat poet Allen Ginsberg. Yet at no time did he even hint that those invitations should not be sent.

In March–April 1967 especially, he was stalwart. During the week before the Impact weekend, in the face of multiple front-page editorials in the Nashville Banner against Vanderbilt hosting King and Carmichael, Chancellor Heard never wavered. When a resolution was adopted by the Tennessee Senate questioning the university’s judgment for allowing Impact to bring these speakers, he never wavered. When his job was on the line at the May 1967 trustees meeting, his support for Impact and the open forum never wavered. Nor did he ever criticize or blame the students involved in Impact—not in 1967, nor later.

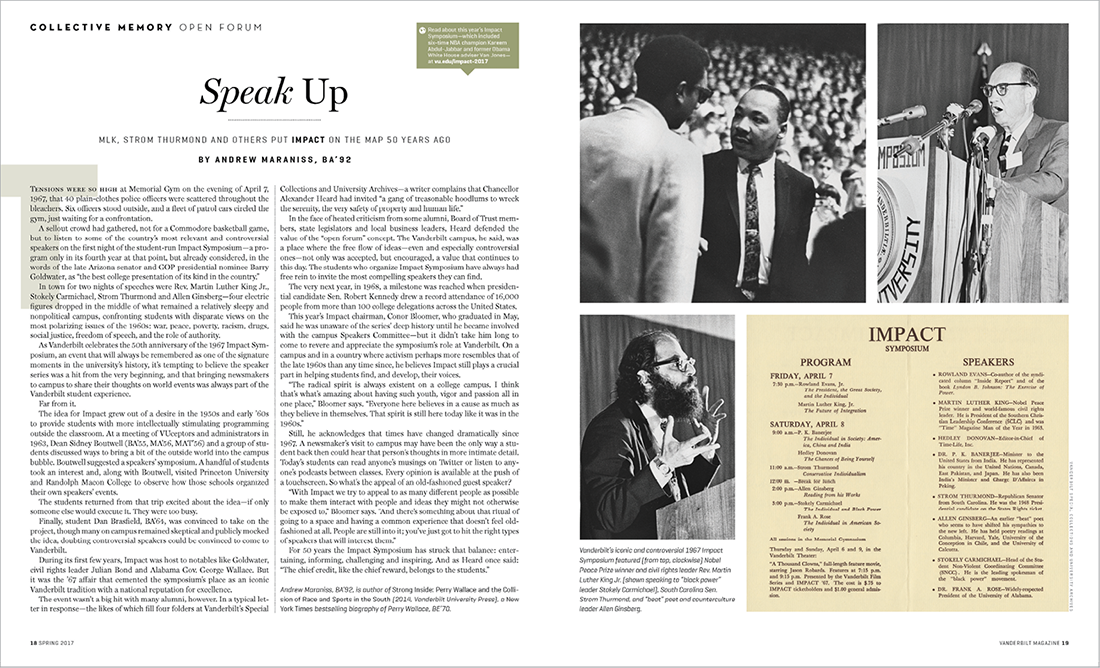

Impact ’67 was historic. It did have a roster of “electric speakers.” It was featured on local television news and newspaper front pages for many days. Attendance exceeded 4,000, making Impact ’67 probably the largest nonathletic student-organized event in Vanderbilt history up to that time. Despite off-campus efforts to stoke controversy, it was a huge, exciting, and completely civil, celebration of the open forum at Vanderbilt. But that did not make it historic.

Impact ’67 has a significant place in Vanderbilt history because events after the program ended emboldened powerful trustees and alumni to attempt to sack the chancellor, who was inextricably linked to Impact ’67.

The criticism leveled at Heard the week before the program took on a greater dimension the night after the program ended. That night an “incident” occurred in north Nashville involving SNCC members, Tennessee State University students and the police. Police made some arrests. (Subsequent investigation showed the police had initiated the incident.)

Front-page coverage and commentary on that incident fueled public blame of the chancellor and Vanderbilt for bringing inflammatory speakers [to campus]. These events gave the chancellor’s opponents, including some trustees such as Banner publisher James Stahlman, an opening to seek removal of a chancellor who was changing Vanderbilt in fundamental ways that they disapproved—including Heard’s support for Impact ’67.

That challenge culminated at the May Board of Trust meeting at which Heard’s job was on the line: His opponents held him responsible for Impact ’67 and its aftermath. Heard again did not waver in his support for Impact and the open forum. He won the trustees’ support and retained his job.

Impact ’67 is indeed a “signature moment” in Vanderbilt history, partly because of the speaker roster, but primarily because its aftermath precipitated a showdown over Alexander Heard’s vision for the university as a vibrant national academic institution with a truly open forum. That vision was validated and fueled the trajectory of Vanderbilt as a national university from 1967 to today.

DAN BRASFIELD, BA’64

Tupelo, Mississippi

WAYNE HYATT, BA’65, JD’68

Tempe, Arizona

TOM LAWRENCE, BA’67, JD’72

Nashville

BOB EAGER, BA’67*

Potomac, Maryland

FRYE GAILLARD, BA’68

Coden, Alabama

*Bob Eager’s name was omitted in the print version of the story. Vanderbilt Magazine regrets the error.