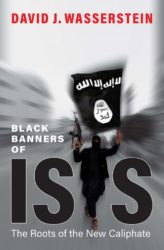

Listen to an interview with David Wasserstein about his book Black Banners of ISIS >>

Events didn’t go as many Westerners expected when ISIS occupied the cities of Raqqa and Mosul two years ago.

“When ISIS got to those cities, particularly Mosul, they found large populations of Christians,” said David Wasserstein of Vanderbilt University, author of a new book about ISIS, Black Banners of Islam: The Roots of the New Caliphate.

“The impression we have is that ISIS loves violence and killing people and especially killing Christians. The fact is that in neither case did they unleash their soldiers on a wild spree of killing.”

Instead, ISIS forced a pact on Christians which allowed them room to exist, but under stringent conditions. For example, they may pray in their churches, but they may not renovate them or build new ones. They may not ring church bells or pray so that Muslims can hear. And they have to pay a special tax as Christians.

All this and more represents a deliberate desire to go back to the past, Wasserstein says. In the seventh century, when Muslims emerged from Arabia and conquered vast areas of the Middle East, they imposed similar conditions on the Christians (and Jews) whom they found there.

What ISIS is trying to do is recreate the conditions of the seventh and eighth centuries, when Muslims ruled the greatest empire the world had seen, Wasserstein says. Their legal and administrative arrangements, like much else in their behavior, can be explained in terms of that desire. When ISIS kills people, similarly, it does so in terms of their understanding of the models of the distant past.

One such model is the caliphate. The caliphs of the seventh century were the successors to the Prophet Muhammad, representing the majesty of Islam in its glory days when Muslims ruled a vast empire and Christians and others were subject to them. “Harun al-Rashid, of the 1001 Nights, is a literary fiction,” Wasserstein says, but “that fiction is solidly rooted in historical reality.”

One such model is the caliphate. The caliphs of the seventh century were the successors to the Prophet Muhammad, representing the majesty of Islam in its glory days when Muslims ruled a vast empire and Christians and others were subject to them. “Harun al-Rashid, of the 1001 Nights, is a literary fiction,” Wasserstein says, but “that fiction is solidly rooted in historical reality.”

ISIS takes seriously the idea that what the Quran says is literally true. So when suicide bombers blow themselves up, they do so in the conviction, founded in their understanding of the Quran, that their action will take them to paradise. “Paradise beckons,” says Wasserstein, Eugene Greener Jr. Chair in Jewish Studies.

In the book, Wasserstein argues that if we are to defeat ISIS successfully we need to understand it. That means studying the texts and radio addresses and videos it puts out. That means seeing it not simply as an army of gangsters out to kill and loot and rape for the sheer satisfaction that gives. Rather, we should see ISIS as having a coherent and serious ideology – none of which is secret or hidden – growing out of an extremist interpretation of the early history of Islam and the experience of Muslims.

Only that will make it possible to go beyond the first vital step, of crushing ISIS militarily, to the next step of defeating the ideology itself. What is needed, Wasserstein says, is for Muslims to understand, not from westerners but from other Muslims that the ideas being sold by ISIS do not represent either the mainstream of Islam through history or an authentic interpretation of the faith preached by the Prophet in the seventh century.