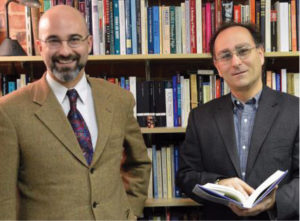

With partisan battles raging in Washington, online and around the world, it seems like society has fallen into one long, hopeless shouting match. Not so, say Vanderbilt philosophy professors Robert B. Talisse and Scott F. Aikin, authors of Why We Argue (And How We Should): A Guide to Political Disagreement (2014, Routledge). They also host a new podcast called Philosophy15, which offers bite-sized discussions of philosophic issues.

With partisan battles raging in Washington, online and around the world, it seems like society has fallen into one long, hopeless shouting match. Not so, say Vanderbilt philosophy professors Robert B. Talisse and Scott F. Aikin, authors of Why We Argue (And How We Should): A Guide to Political Disagreement (2014, Routledge). They also host a new podcast called Philosophy15, which offers bite-sized discussions of philosophic issues.

“Argument remains the main resource we have for seeking the truth, assessing our ideas, challenging our perspectives and improving our beliefs,” says Talisse, the W. Alton Jones Professor of Philosophy and chair of the department. “Despite the risks of hostility, we must argue with each other. The challenge is to argue well.”

Here are some rules of thumb:

1. AVOID THE “SIMPLE TRUTH” TRAP.

Whether you disagree about politics, religion, or just which city makes the best pizza, it’s easy to think that someone has just missed a very simple truth, says Aikin, MA’03, PhD’06, assistant professor of philosophy. “The ‘simple truth’ thesis says that obvious pieces of common sense can be missed only if one is deeply corrupted in some way—by one’s education, ideology or upbringing. But if you start with the assumption that the other person is rational, the simple truth thesis can’t be right.”

2. DON’T STEREOTYPE.

Opposite sides in deep disagreements tend to have not only an entrenched view of what’s right or wrong, but they also have built-in perceptions about the people who hold those views. “Every conservative has a stereotype of, say, the liberal professor or the women’s studies major; and every liberal has a stereotype of, say, those who prefer market solutions to labor problems or those who endorse the death penalty,” Talisse says. But those stereotypes are products of the way one side has represented the other side in debates, he says, adding that these characterizations often leave out important details that may make an argument better than you’d anticipated.

3. MAKE YOUR PREMISE CLEAR.

“Arguments require that we be clear about what we are reasoning from and what we are reasoning to,” Talisse says. When people themselves aren’t clear about their starting premise, the argument itself won’t be clear. “This defeats the point of arguing.”

4. CONCEDE A GOOD POINT.

“If your interlocutor has a good point, concede it. Revise your view accordingly,” Aikin admonishes. “The whole point of the discussion is to see what can pass the test of critical reasoning, and if your view doesn’t pass the test, get rid of the troublesome parts.”

5. BE PATIENT.

Recognize that deep disagreements likely won’t be resolved in just a short conversation, or even a single exchange. It takes a long time to hash out big disagreements, Talisse says: “This is because, first, it is hard to change one’s mind, and second, because a significant disagreement arises often because there are many contributing factors. They all need to be addressed before there can be adequate resolution.”

TEXT BY JIM PATTERSON, MLAS’15

ILLUSTRATION BY GARY WATERS