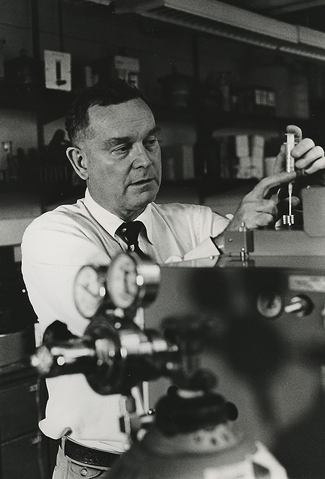

Professor Emeritus of Chemistry David James Wilson died peacefully Jan. 12 in Belleville, Michigan, following a three-year bout with melanoma. He was 86.

Wilson was a member of the chemistry department at Vanderbilt for 26 years until he retired in 1995. Before coming to Vanderbilt, he taught at the University of Rochester for 12 years. By the time he retired, Wilson had published three books and about 300 journal articles and had supervised the research projects of 34 Ph.D. students and a comparable number of master’s and undergraduate researchers and high school science fair participants.

Wilson’s early research emphasized quantum and classical theoretical methods for investigating chemical kinetics problems at the level of atoms and molecules, and included a paper that has been recognized as a landmark contribution to chaos theory.

Wilson taught courses at all levels, from freshman to advanced graduate, always with enthusiasm and concern for his students’ success. In discussing student missteps in problem-solving, his trademark wry comment was “managed to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory.” He once defined higher education as “that unusual enterprise where the customer pays top dollar and then refuses to take delivery of the product.”

In the 1960s, while living in Rochester, Wilson became involved in environmental advocacy when he joined efforts to remove lead paint from old houses. He also participated in a campaign to stop sewage contamination of Lake Ontario beaches from an outdated treatment plant and received a sportsman-conservationist award in 1967 for his efforts.

His environmental interests became the focus of his scientific research after he arrived at Vanderbilt. He and his research group developed methods for removing pollutants from air, water and soil. In 1983 he was the first recipient of Vanderbilt’s Alexander Heard Distinguished Service Professor Award, which recognizes “contributions to the analysis and solution of contemporary social problems.”

In Nashville, Wilson also continued his “citizen scientist” efforts, helping to identify a large hazardous waste site in West Tennessee and serving as chair or president of several organizations, including the Tennessee Environmental Council and the Tennessee Academy of Sciences. Through the academy and through his involvement in the Boy Scouts, Wilson inspired science studies by school students and mentored many in science fair projects. He also helped bring the International Science and Engineering Fair to Nashville in 1992.

In an address given at a Vanderbilt Phi Beta Kappa meeting in 1981 titled “Environmentalism – Coping with Hard Times,” Wilson noted that while environmental justice can be achieved in courts of law, the “court of public opinion” can be both faster and more satisfying.

After he retired from Vanderbilt, Wilson consulted for several years at Brown and Caldwell, a Nashville environmental engineering firm. In 2003 he moved to Michigan to be close to his children and grandchildren. There he established a watershed ecology program for local schools. His final environmental fight led to the banning of coal-tar driveway sealants in his township.

Wilson leaves behind his wife of 64 years, Marty; four sons; a daughter; and 10 grandchildren. The family is planning a celebration of his life on April 2 at the Pittsfield Union Grange in Ann Arbor. Donations in his honor can be made to the Huron River Watershed Council in Ann Arbor, Michigan, or to any other organization of the donor’s choice.