When the Common Core State Standards were first introduced, some balked at its math recommendations, including using a number line to teach fractions. Now, results of a new Vanderbilt study suggest the approach is actually quite effective.

Lisa Fazio, assistant professor of psychology at Vanderbilt’s Peabody College of education and human development, is lead author of the study, which was published this month in PLOS One.

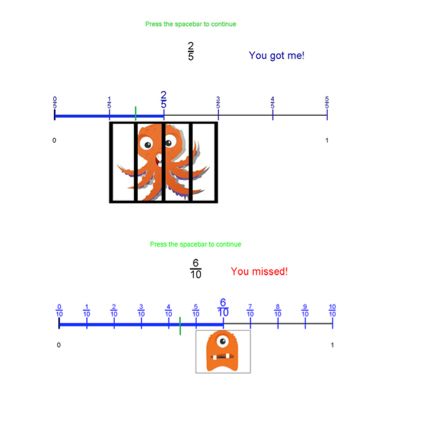

For the study, Fazio developed a computer game, Catch the Monster with Fractions. In a short 15-minute intervention, fourth and fifth graders were given brief instructions about unit fractions before playing the game. When playing, students were prompted to find a particular fraction on the number line. When they clicked on the location where they believed the fraction should be, a cartoon monster popped up and said, “You got me!” or “You missed!”

The study had two phases, both yielding encouraging results. In the first phase, children showed large gains from pretest to posttest in their fraction number line estimates, magnitude comparisons and recall accuracy. In the second phase, the experimental group showed similarly large improvements, compared to the control group, which, in the absence of the instructions about unit fractions, showed no improvement.

“The results provide evidence for the effectiveness of interventions emphasizing fraction magnitudes, including number line estimation and memory for fractions,” Fazio said. “However, such activities must include well-designed feedback. Practicing placing fractions on number lines alone is insufficient to improve student knowledge.”

The intervention was at least as effective for children who started with less knowledge as for those who started with more, the findings suggest. In fact, children who started with lower knowledge showed greater improvement. Even children who were unable to finish the game in the allotted time showed improvement in fraction estimation accuracy and memory for fractions.

Fazio says the introduction of fractions is often the reason students in lower grades get frustrated over math, and the first signs of math anxiety appear.

“Kids develop this really strong understanding of whole numbers. Then we teach them fractions, and it blows up everything they have learned about how numbers behave. The instruction, along with the game, provides a fun way to learn fractions without the anxiety,” she said.

On a recent report from the National Assessment of Educational Progress, only 49 percent of U.S. eighth graders were able to correctly order three fractions from least to greatest. The NAEP also found that only 55 percent of eighth graders could correctly solve a simple word problem involving fraction division.

“This is a serious problem, because understanding of fractions is a foundational mathematical skill, and early fraction knowledge strongly predicts later math achievement,” Fazio said. “Without a good grasp of how fractions work, Algebra learning will be severely hindered.”

Collaborators on the study were Casey A. Kennedy, Department of Psychology, Carnegie Mellon University; and Robert S. Siegler, The Siegler Center for Innovative Learning, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China.

Read the full report, “Improving Children’s Knowledge of Fraction Magnitudes,” in PLOS One.