BY ANDREW MARANISS, BA’92

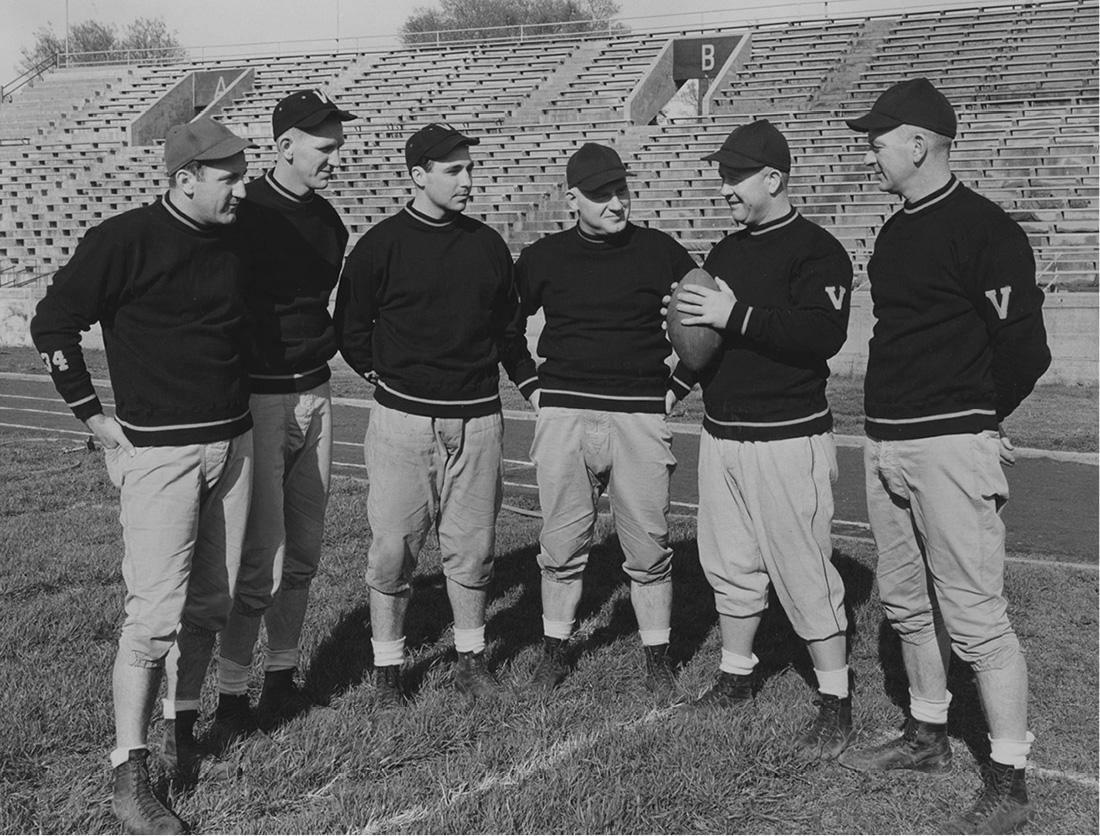

It’s Friday, Oct. 11, 1940. A young Vanderbilt assistant football coach takes an anxious drive out to the countryside while head coach Red Sanders lies in a bed at Vanderbilt Hospital, recovering from an emergency appendectomy. There’s no way Sanders will recover in time to take the field the next afternoon to lead the Commodores against heavily favored Kentucky, just the third game of the new coaching staff’s first season at Vandy.

That means this young assistant will step in as head coach for the game, to be played in front of an expected crowd of 15,000, the most ever to witness a tilt between the Commodores and Wildcats in Nashville.

The young coach pulls his car over to the side of the road, his stomach jumbling with nerves.

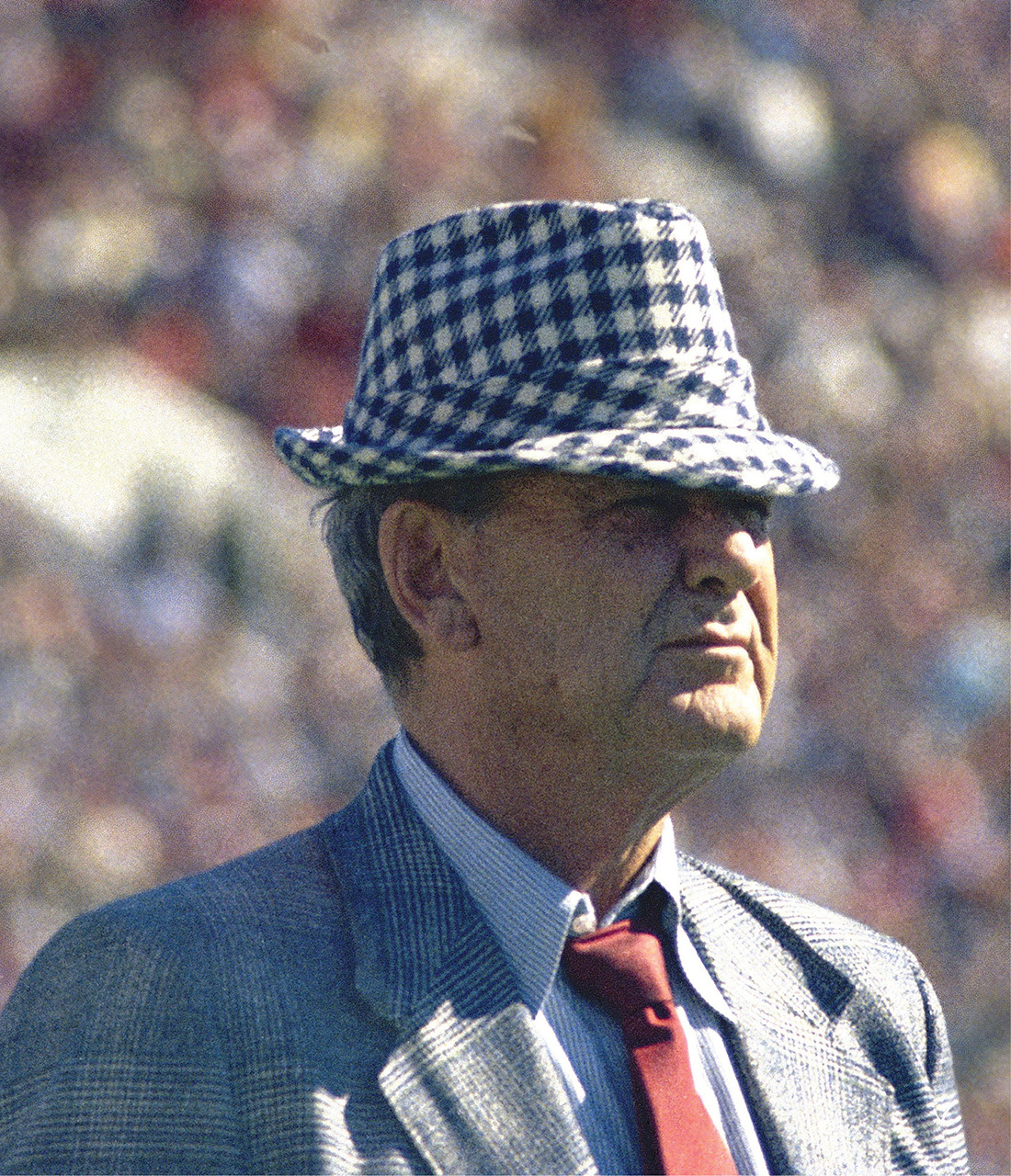

In a coaching career that would span 44 seasons, including six as an assistant and 38 as a head coach, this young man would go on to win 323 games, 14 SEC championships and six national titles. Upon his death in 1983, he had won more games than anyone in the history of college football, and to this day many still consider him the greatest college football coach of all time.

But on the night before he coached his first game as an emergency fill-in at Vanderbilt University, Paul “Bear” Bryant puked his guts out.

No doubt Bryant is the most legendary figure ever to walk the sidelines at Dudley Field as a Vanderbilt assistant, but the list of former assistants includes a number of impressive names, notable for their achievements in college and professional football. Consider just a few:

• Wallace Wade, an assistant to Dan McGugin in 1921–22, went on to win three national championships as head coach at the University of Alabama, and his 1938 Duke team did not allow a single point until the final minute of the season finale, the Rose Bowl. The Blue Devils’ stadium in Durham, North Carolina, is named after him.

• Buddy Ryan, who passed away earlier this summer, enjoyed a 28-year professional coaching career, beginning with the Super Bowl III-winning New York Jets, serving as the fiery defensive coordinator of the 1985 Super Bowl-winning Chicago Bears, and as head coach of the Eagles and Cardinals. Ryan was defensive line coach at Vandy in 1966, his final season at the collegiate level.

• Phil Fulmer, the longtime coach at rival Tennessee, where he won a national championship in 1998, cut his teeth as a Vanderbilt assistant under George MacIntyre in 1979.

• Bill Parcells, the NFL Hall of Fame coach who won two Super Bowls with the New York Giants and later coached the Patriots and Cowboys, was the Commodores’ defensive coordinator in 1973 and during the Peach Bowl season of 1974.

There are loose Vanderbilt ties to three other legendary coaches, men who could stake claims to ranking as the most successful in the history of professional and college football. New England Patriots coach Bill Belichick—he of the gray hoodies and four Super Bowl titles—was born in Nashville when his father, Steve Belichick, was a Commodore assistant under Bill Edwards from 1949 to 1952.

Vince Lombardi’s grandson John was a graduate assistant under Vanderbilt’s Rod Dowhower. And Bobby Bowden, who retired from Florida State in 2009 with two national titles and 377 wins to his credit, never coached at Vanderbilt, but he does have a Vanderbilt degree, having earned his master’s from Peabody College in 1953.

“THIS AIN’T MURRAY!”

The story of Vanderbilt and Bear Bryant begins with sportswriter Fred Russell, ’27, as does just about any story involving Vanderbilt and a legendary sports figure of the 20th century.

Russell, then sports editor for the Nashville Banner, first met Bryant in 1937 when they sat next to each other on the train carrying Alabama’s football team to California for the Rose Bowl. Bryant was the youngest assistant coach on that Tide team, and when Red Sanders was named Vanderbilt’s coach in 1940, Bryant remembered his long conversation with Russell and called to ask for his help in making a connection to Sanders.

Red was looking for a right-hand man (a step up from Bryant’s more junior position at Alabama), but he told Russell that while he’d consider Bryant, his top choice was a former Tennessee player named Murray Warmath. When Sanders called Russell a few days later and told him his new assistant coach would like to speak to him, Russell greeted the caller with, “Murray, I wish for you some fine years at Vanderbilt.”

“This ain’t Murray,” answered the man on the other end of the line. “This is Bear!”

Bryant and his wife, Mary Harmon, arrived in Nashville and settled into a house on Central Avenue. He became known as such a tough disciplinarian that when he made his nightly visits to Kissam to enforce curfew for his football players, even students who weren’t on the football team averted eye contact lest they be ordered to run the stadium steps. When Bryant spotted tailback Art Rebrovick, BA’43, drinking a Coca-Cola on campus with his girlfriend, Bryant made Rebrovick run at practice—for two and a half hours straight. Rebrovick would never look at a Coke the same way again.

Bryant threw himself into his work with passion, challenging his players to sprints, jumping into the huddle without pads during practice. He was demanding, but his players loved him. A big baseball fan, he was even known to pitch batting practice to the Commodore baseball team. (And in his love for America’s Pastime, a connection to Parcells: Former Vanderbilt baseball coach Larry Schmittou, BS’62, recalls Parcells’ penchant for popping into the Commodore dugout, and accompanying Schmittou to high school baseball games around town.)

Bryant’s arrival on campus preceded the United States’ entry into World War II. Headlines in the days leading up to the Kentucky game alerted readers to German bombing runs on London, Japan’s signing of an alliance with Germany and Italy, and Neville Chamberlain’s resignation from the British Cabinet.

In South Bend, Indiana, the cast of Knute Rockne: All American, starring Ronald Reagan as George Gipp, appeared at Notre Dame for the movie’s world premiere, and the Knickerbocker Theater in Nashville advertised it was showing the film in which the Irish win one for the ailing “Gipper.”

“NEVER A NOBLER VANDERBILT TEAM”

The situation was nearly the same on West End, where Bryant and his players were desperate to win one for Red. On game-day morning Bryant gathered his Commodores in their locker room, where they listened over the telephone to a pregame pep talk from their ailing coach in his hospital bed. Sportswriters standing outside observed numerous “tear-stained eyes” as the players ran onto the field to face an undefeated Kentucky team.

The Commodores led the game 7–0 until the final two minutes, “when fate stepped in and human endurance gave out,” a newspaper account revealed. The Wildcats scored, and the game ended in a 7–7 tie. Given Kentucky’s talent advantage, the outcome was considered the biggest upset in the nation, and Bryant received all due praise. “Acting coach Bryant,” opined The Vanderbilt Hustler, “did a splendid job of shouldering his responsibility.”

“In 50 years, never a nobler team,” claimed the Nashville Banner.

Sanders was back on the sidelines for the Commodores’ next game, at Georgia Tech, and Bryant’s stint as head man was over. Vanderbilt finished the season 3–6–1. The next year, 1941, with Sanders and Bryant still on the sidelines, the team improved to 8–2. Eight days after the final game of the ’41 season, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, Bryant enlisted in the Navy, and his days at Vanderbilt were over forever.

Through head coaching stops at Maryland, Kentucky and Texas A&M, and then his stellar run at Alabama from 1958 to 1982, Bryant remained close friends with Fred Russell and his family. (Before taking the job at A&M, he even confided in Russell a desire to return to Vanderbilt as head coach).

Whenever Bryant’s Alabama teams came to Nashville, he always made a point to visit the Russell family on Brighton Place. When Russell’s daughter Carolyn delivered her first child, it was Mary Harmon Bryant who was first to hold the newborn. And Bryant never forgot the first team he led into battle, the outmanned Vanderbilt Commodores of Oct. 12, 1940.

Four decades later, at a National Football Foundation banquet in Nashville, a halfback on that 1940 team, Binks Bushmaier, approached his famous former coach. “If you count that game as your first as a head coach,” he asked, “do you remember who scored your first touchdown?”

How could Bryant possibly remember, Bushmaier worried. How many countless touchdowns had his players scored in four decades of coaching? Did Bryant’s flicker of time at Vanderbilt still mean anything to him?

“You did,” Bryant replied, to Bushmaier’s delight. “On a pass from Mickey Flanigan.”

Andrew Maraniss, BA’92, is author of the New York Times best-seller Strong Inside: Perry Wallace and the Collision of Race and Sports in the South (2014, Vanderbilt University Press), which was selected as this year’s Ingram Commons Reading for all incoming Vanderbilt first-year students. Connect with Andrew on Twitter @trublu24.