EDITOR’S NOTE: This essay is adapted from The Long View: Essays, Poems, Stories (Cordelia Hollis, 2015) by Susan Ford Wiltshire, Vanderbilt professor of classical studies, emerita. Wiltshire wrote this piece as a letter to her daughter, Carrie Wiltshire McCutcheon, JD’05, who is an attorney at Baker Donelson law firm in Nashville. Today women play a vital role in Vanderbilt University’s success: 53 percent of the undergraduate population, four vice chancellors and four school deans are women.

Dear Carrie,

You asked me to tell you about WEAV and the Langland case. This all happened at Vanderbilt University more than three decades ago. You were 5 years old when it began and 8 when it ended. I have three distinct memories of your involvement, which I will recount in due course.

I will begin with the facts of the matter, then tell you the lessons we learned in pursuing it. In 1975 the English department at Vanderbilt hired Elizabeth Langland as an assistant professor. One of her new colleagues said at the time, “She is one of the two brightest new Ph.D.’s in English in the country, and we got her.” Shortly after she arrived, Elizabeth was also appointed to head the Women’s Studies Committee. We still had no program or full-time director. Among Elizabeth’s research interests was the study of women in literature, and she was already publishing pioneering material in the field.

In time Elizabeth was recommended by her department for promotion with tenure, the first woman ever to be recommended for tenure in the hundred-year history of the English department. The vote was 15 to five. We knew the identities of four of the five opponents—the same ones who resigned from the Episcopal Church when it started ordaining women. We were delighted by the other 15 votes and the positive decision, though not surprised. Elizabeth was and is that good.

Several months later and after delaying word of his decision long after the usual announcement time in the spring, the dean of the college called the head of the English department on a Saturday morning in June—just before he left on vacation and when the campus was deserted—to say he did not concur with the department’s decision and it would not go forward. Elizabeth would have to leave Vanderbilt after one more year.

Elizabeth called when she heard. I asked her what she was going to do about it.

“I’m going to fight it,” she said.

“Why?” I asked.

“So my daughter won’t have to.”

“Good. Then I will help you,” I said. “And we will do it in such a way that we win, even if we lose.”

First we had to go through the channels of the university. There weren’t many then except for the provost and the chancellor. No one in the administration would reverse the dean’s decision. That’s when I learned that superiors generally support their subordinates publicly even when they know they are wrong.

After that we had to submit the case to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the federal agency that oversees discrimination laws. The EEOC refused to consider the case—we learned later that Clarence Thomas was head of that agency at the time—but we had to go through that procedure as a prerequisite to filing the case in federal court.

In choosing a lawyer, we were determined to get the strongest attorney in town who was not afraid of Vanderbilt. After consultation we chose George Barrett, JD’57. I don’t remember exactly when the case was filed in the federal court for the Middle District of Tennessee, but the judge was Clure Morton. On the day we filed the lawsuit, Vanderbilt announced it would establish a day care center on campus—something we had been advocating for more than a decade. That was our first victory.

After many depositions and what seemed like a very long time, Judge Morton ruled against us. That was the day, so I heard, that the chancellor called the dean to instruct him to appoint a full-time director of women’s studies, a position we had been lobbying for since the origin of the Women’s Studies program in 1973. Another victory.

Then our lawyers appealed the case to the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals in Cincinnati. In 1984 they affirmed the district court’s ruling. The appeals court’s judgment ended the lawsuit.

At every level of Elizabeth Langland’s case, from the English department’s decision to that of the federal Court of Appeals, every vote was cast by a male.

Here is some of what we learned along the way. The following list of 10 is not in order of importance, except for the first three. They are all—so to speak—interwoven.

1. Organize.

What the dean could not have known when he delivered his decision that fateful Saturday morning was that we were ready and waiting. We had lost five key women from various positions in the preceding year. Further, in the 10 years since I had been hired in 1971, 30 women had come and gone from the faculty of Arts and Science, leaving Vanderbilt either because of negative tenure decisions or because of discouragement that they would never even get to that point.

Elizabeth called when she heard. I asked her what she was going to do about it. “I’m going to fight it,” she said. “Why?” I asked. “So my daughter won’t have to.”

Faculty and staff women had been meeting informally throughout the year to discuss these disturbing issues, sometimes conferring also with the two or three women on the Board of Trust, and we already had scheduled a meeting for the following Monday night.

In organizing anything the first task is to identify the cause clearly and name it accurately. We knew from the beginning that we wanted to change the status of women at Vanderbilt. Our purpose was never simply “Support Elizabeth Langland.” None of us, including Elizabeth, ever saw it that way.

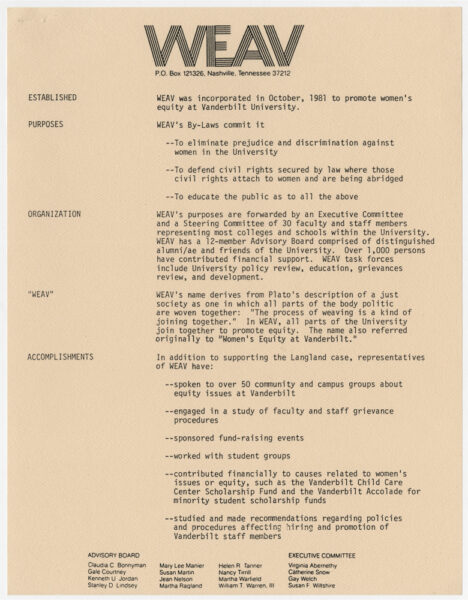

We were fortunate to have a name already at hand. WEAV stands for “Women’s Equity at Vanderbilt.” It was suggested by a description Plato gives of the ideal ruler as one who weaves together the body politic—“the type of character fitted for the task of weaving together the web of state.” All strands must be included to ensure the fabric is strong.

In our organization, staff and faculty women would always have joint leadership roles. It was the first time at Vanderbilt that faculty and staff groups had worked together on equal terms. This collaboration spread throughout the campus. Soon we learned that the secretaries knew more about what was really going on than the faculty did.

From the beginning we met regularly, usually on Wednesdays at noon. We began publishing an attractive newsletter, always printed on 100 percent bond paper. A staff member, Catherine Snow, insisted that if we were going to do it, we would do it with style.

We knew, too, that we were working in an honorable tradition: In 1920, thanks to the work of noble women and supportive men, Tennessee had become the 36th and final state necessary for the passage of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution giving women the right to vote. Following one of the suffragists’ examples of fundraising, we hosted a Silver Tea in which attendees contributed silver coins to the cause. We wore yellow roses, as they did, as a sign of our support.

We also organized a “Carrie Chapman Catt Day” on campus. The great suffragist leader Carrie Chapman Catt had spent six weeks in Nashville organizing the final push for the vote on the 19th Amendment in the Tennessee legislature. The amendment passed by a margin of one vote. WEAV’s honored guest that day was Claudia Bonnyman, JD’74, whose great-grandfather A.H. Roberts was the Tennessee governor in 1920. After the legislature’s vote, it was he who signed the certificate of ratification that ultimately changed the U.S. Constitution.

Throughout our efforts, countless allies, including many men, came from all quarters. Dean Walter Harrelson of the Divinity School was a constant friend and adviser. When a member of the administration said to him, “You are being used by these women,” he responded, “I am here to be used.” Don Welch and Frank Wcislo appeared on a panel sponsored by WEAV featuring fathers who were significantly involved in child-rearing. C.M. Newton, Vanderbilt’s superb basketball coach, was friendly to our cause, and we decided to ask him to host an educational gathering at his home.

2. Publicize.

One of the first things we realized was that women who attended Vanderbilt in the 1950s or earlier were strong and smart individuals. In those years only women applicants had to take the Scholastic Aptitude Test because only one woman could be admitted for every four men. Even when I arrived in 1971, the ratio required that three men be admitted for every two women.

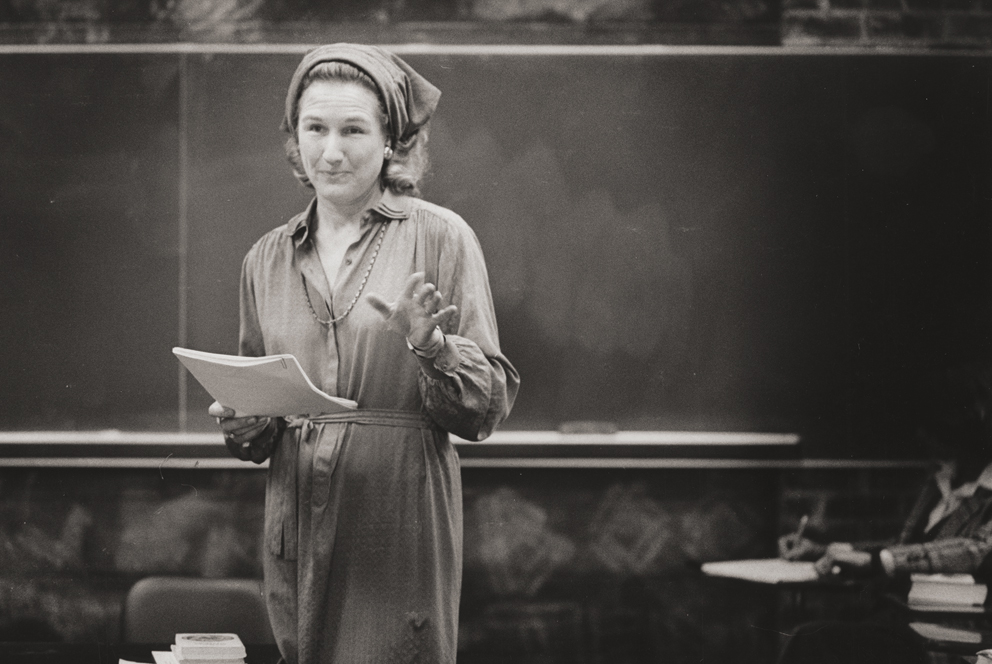

These alumnae, especially Martha Warfield, BA’47, became our strongest supporters in the community. They got together with their friends, and over the course of three years, various ones of them sponsored a total of 34 “educational gatherings” in their homes. Initially, Elizabeth and I would go to speak about the situation of women at Vanderbilt and what we hoped to do about it. After Elizabeth left for a stellar academic career, I often went alone.

Publicity is not limited to newspapers, but in those days the newspapers helped. Carrie, you may remember that one Sunday as our family was driving back to town from the farm, we stopped at Tubby’s in Vanleer to pick up a copy of The Tennessean. Sure enough, there was a big story about the Langland case on the front page of the B Section. Below the headline were two quotations—one from Susan B. Anthony and one from Susan F. Wiltshire. I don’t remember what I said in the quotation, but I do remember what your father [Ashley T. Wiltshire, JD’72] said to me later: “I’m sure there were many reasons for you not to change your name when we married, but I’m proud you did.”

On a New Year’s morning in the middle of the case, I received a call from [Nashville minister and civil rights activist] Will Campbell. “Susan,” he said, “I’ve been looking around for a little trouble to get into, and I don’t see any better trouble than what you women are doing over at Vanderbilt. Here’s what I’m going to do.” He said we needed national publicity. He didn’t stop until he got it—a story by Frye Gaillard, BA’68, in The Nation magazine. I learned that day from Will never to ask, “What can I do to help?” Just go ahead and do it.

We made T-shirts, too. They were dark green with gold letters WEAV down the left side: “WEAV Expects Action, Vanderbilt.” We wore them during a corporate challenge run in Nashville, and the paper printed some nice photos of our team.

3. Raise Money.

There are two reasons to raise money for a good cause.

The first is that you will need it. In our case, we needed it initially to support our publicity campaign, including buying that lovely cream-colored 100 percent bond paper. We also rented a mailbox at the Acklen Station post office. We were scrupulous about not using Vanderbilt’s campus mail for our purposes, which meant we bought lots of postage.

We also needed to pay the filing fee for our IRS 501(c)(3) status as a tax-exempt charitable organization. An endearing thing happened after we appeared before the local Charitable Contributions Board to request our Metro permit. Joseph Sweatt was chair of the board at the time and had asked us some rather stern questions. The board approved our request. As we were leaving, Joe came up to us in the hall, smiled and said, “Good luck. I used to work at Vanderbilt. It’s about time.”

Finally, we suspected we would be funding a lawsuit.

The second reason is more important. When people contribute financially to a cause, they buy into it and are invested in the outcome. The relationships made in asking for contributions also help build a strong community around one’s purpose.

I have many happy memories of people who gave money to WEAV. The first person to contribute was Tom Brumbaugh, a kind professor in Art History. I remember going to a secretary in the Divinity School to tell her what we were doing. She pulled out her wallet, gave us everything in it, and said, “I have been waiting 20 years for this.” Another friend calculated how much money she had spent on new living room furniture and gave WEAV the same amount. A single mother in a staff position pledged $1,000. We even received a contribution from an official in the Reagan administration. (I never added that the contributor was my brother John.)

One day two of us went to call on Mary Jane Werthan, BA’29, MA’35, a member of the Vanderbilt Board of Trust. Legally, the Board of Trust was the ultimate defendant in the lawsuit. We asked her if she would help us raise $5,000. She smiled and said, “I’ll try.” One of the contributions that meant most was one we didn’t ask for or know was coming. A check for $500 arrived in the mail one day with a note from Anne Roos, saying that another check in the same amount would be coming soon.

We held one major fundraiser, a benefit concert at Langford Auditorium featuring Riders in the Sky. Catherine Snow organized this endeavor and saw to it that we sold tickets in advance. That’s when I learned never simply to set up an event and hope people come. The auditorium was nearly full. For the finale, the Riders sang “Home on the Range.” I never thought of “Home on the Range” as a movement song, but it is. Spontaneously, we all stood up, joined hands, and began to sing, “Where seldom is heard a discouraging word / And the skies are not cloudy all day.”

In all, we raised about $60,000.

You contributed, too, Carrie. One day you came up to me in the kitchen with a bill in each hand. “I have a one dollar bill, Mommie, and a five dollar bill. I can’t decide which one to give to WEAV.” You thought a moment and said, “I think I’ll give my five dollar bill, so they’ll know I really mean it.”

4. Expect Insults.

Several times I heard, “You have a good issue, but this is not a good case.” The dean of the business school said to me, “I’ve asked around about you. You are a good teacher and a leader, but you are no scholar.” What that had to do with the Langland case I’m not quite sure, but it did hurt my feelings. For a while.

The college dean insulted all of us when he was quoted in a local newspaper as saying that research in women’s studies is not real scholarship.

Then there was this: “I don’t know what Susan’s complaining about. She’s had a lot of advantages here because she’s a woman.” If that had been said to my face, I would have replied: “This is not about me.”

The ugliest insult came in a meeting of the Faculty Senate. Elizabeth was elected to the senate after her negative decision, and I was already on it. We usually sat together. One day an older woman, a professor in the medical school, rose to speak.

She began poignantly enough. She said that if anyone wanted to know about discrimination against women at Vanderbilt, they wouldn’t believe the things that had happened to her at the medical school. Then she turned toward Elizabeth and me and said, with anger on her face, “You women, quit whining. You make me ashamed.” Maybe there was only a scattering of applause in the room, but it sounded like a thunder roll.

That made me mad, but another incident troubled me more. A staff woman, an editor of a campus publication whom I admired and considered a friend, said to an assistant who reported it to me: “Susan used to have such good judgment, but she’s gone off the deep end about this.” I called Will Campbell about it. “The deep end is for grown-ups,” he said. “The shallow water is where the kiddies play.”

5. Fear Not.

Courage is not a gift endowed at birth. It is a habit earned by practice and by observing the courage of others. I have heard that the words “fear not” appear 56 times in the Bible. I have not counted them, but I do know that only those without fear can be generous.

As far as I know, none of us actively involved in WEAV was fearful of personal or professional repercussions. I still smile when I recall Larry Diamond. Larry was a brilliant young sociology professor without tenure who circulated a petition among other assistant professors in support of Elizabeth Langland. When people asked him if he were afraid to do that, he responded, “What are they going to do to me? Not give me tenure?”

As for myself, I do not remember being afraid of Vanderbilt. I had had some practice by then in questioning institutions, and I was experienced enough to know something about how they operate. The one thing in the academic world I was afraid of, however, was something Vanderbilt could neither give me nor take away: I was afraid of not finishing writing the Vergil book [Public and Private in Vergil’s Aeneid (University of Massachusetts Press,1989)].

Then the oddest thing happened. On the first day of Elizabeth’s federal trial, because I was a potential witness, I was asked to leave the courtroom. I walked out the courthouse door, went straight to my carrel at the Vanderbilt library, and starting finishing the Vergil book. I was not afraid anymore.

6. Know There May Be Failures of Nerve.

Failures of nerve can happen in any long, sustained campaign. The truly dramatic one during WEAV was when Elizabeth Langland called one morning to say she had decided to drop the lawsuit. We had been working for two years by then, and the legal proceedings and tension were at their height.

We called an emergency meeting for that night. Several of us were discussing the dispiriting options of what to do next when Elizabeth walked in the door. She stopped in the middle of the room, smiled at us, and said, “Let’s get back to work.”

7. Have Fun.

As you must know, Carrie, having fun is not my strong suit. I have been on the serious side since childhood. I didn’t gain a real sense of humor until WEAV, and that was because of the explicit effort of our friend Catherine, who made a project of me.

The first challenge to my natural reserve came when someone proposed a “Vandy Runaround.” The plan was to organize a run that passed by places having special significance for women on campus. We were to place posters at key points, which included (1) the Women’s Center, at that time tucked into an attic up a steep outside staircase on West Side Row; (2) the history department, where we had our first women’s studies office in an oversized closet; and (3) the building where two remarkable female professors had offices in the biology department. They had senior positions at Vanderbilt because their chair, Oscar Touster, alone among all the departmental chairs in 1946, refused to fire them after the men came back from World War II.

During this run and at our rally afterward in Underwood Auditorium, we were all supposed to blow kazoos. I didn’t even know what a kazoo was. But we did it, and I did it. That’s when I learned that once you’ve made a fool of yourself for the first time, you’re free to get on with your life.

Another value of having fun is strategic. If you are laughing, it makes the other side wonder what you know that they don’t know.

A time came when we were all so weary that we decided we needed to have a party. We scheduled a potluck dinner at our house. Women started arriving, and you came up to me in the hall—you were 6 or 7 then—and asked, “When is the meeting going to start?”

“We’re not having a meeting, Carrie. We’re having a party.”

“You mean you have all these women here and you’re not having a meeting?”

8. Face Unanticipated Consequences.

This was by far my hardest experience during the lawsuit. It broke my heart and the hearts of many others.

There was a lovely associate professor in the philosophy department. We were friendly colleagues and worked on projects together. He had been promoted with tenure awhile before the Langland case came up.

At one point during the trial, Judge Morton asked to see all the files of people who had recently been promoted to tenure in the College of Arts and Science. This professor’s file was among them. When Judge Morton saw the note the provost had inserted in his file, he exclaimed angrily, “Vanderbilt is going to lose this case right now!” The evening paper reported it under the headline: “Vanderbilt professor would not have been promoted if he weren’t black.”

The young professor and his wife lived at the other end of the block from us. I called Elizabeth immediately to say we had to go down there. We walked up the steps and rang the bell. The wife answered the door. He wasn’t home. She glared at us but opened the door a little more and motioned us in.

We sat down. She said things to us so awful I now suspect even she didn’t mean them. Neither she nor her husband ever spoke to me again.

One might ask the question—and perhaps many did: “If you had known what was in that file, would you have pursued this case anyway?” Our answer was yes.

But think about it. If we had known, here’s what we would have done: We would have gone immediately to the young professor to tell him what was coming. We would have made sure he was surrounded by friends, maybe by his whole department. We would have written a press release for immediate distribution and urged him to do the same.

And perhaps one of us would have gone to the provost to ask him why he never got any of the blame for the note he added to that file.

9. Remember the Restroom.

Think of it as a room to rest in. It’s a good place to go when you need to take off your game face. If you need to cry, it’s the only place to go. You can also retreat there to share confidences with a friend—just be sure no one overhears you. Or maybe you will run into someone you needed or wanted to see.

Then resume your game face, and head back out to take on the world.

10. Wear Nice Clothes.

This seems obvious enough, but it was important to me to look my best during this period, especially at public events. Regardless of any effect on others, it made me feel better.

On the last day Judge Morton was trying the case, I took you out of school to go with me to his court to hear the closing arguments. You wore your pretty gray suit and little Mary Jane shoes. Somewhere we have a picture of you on the steps of the courthouse afterward, standing earnestly by Elizabeth Langland and George Barrett.

You are a lawyer now, Carrie, and you still wear pretty suits and closed-toe shoes to court.

—

The following fall the College of Arts and Science gathered for its annual opening convocation. On that occasion each department introduces the new members of its faculty. The chair of the English department stood up. “We have four new members of our department to present to you,” he said.

“The first is Professor A, who comes here from Princeton. She will hold a senior endowed chair at Vanderbilt.

“Professor B, an assistant professor, is a specialist in Caribbean and African studies.

“Professor C is an assistant professor and specialist in gay and lesbian studies as well as Shakespeare.

“Professor D comes as a tenured English professor and director of the Women’s Studies program.”

All four were women.

We lost the case.

We won the cause.

Love, Mom

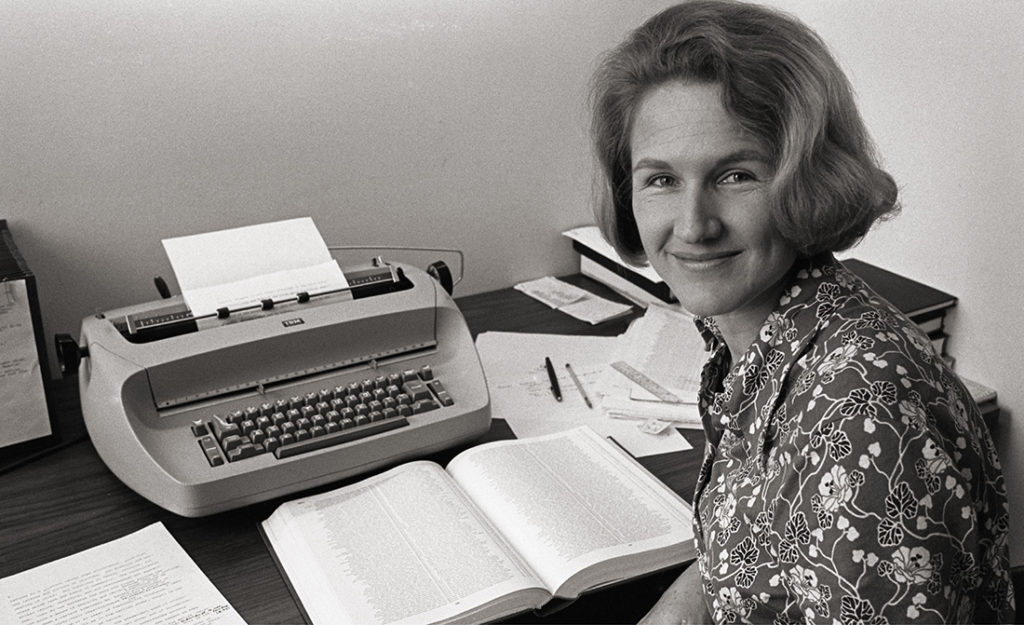

Susan Ford Wiltshire joined the College of Arts and Science faculty in 1971 and retired in 2007 as professor of classical studies, emerita. During her time at Vanderbilt, she was presented, among other honors, the Mary Jane Werthan Award for extraordinary contributions to the advancement of women at Vanderbilt, the Affirmative Action and Human Rights Award, the Thomas Jefferson Award for contributions to the councils and governance of the university, and the Madison Sarratt Prize for Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching.