In what could be a way to predict which children might be vulnerable to anxiety disorders, a Vanderbilt study has shown that an altered prefrontal cortex function in the brain marks a heightened anxiety risk in children.

The prefrontal cortex, located in the front part of the brain, is involved in a wide variety of executive functions, including decision making, planning and organizing.

The study in the September issue of Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, authored by Vanderbilt’s Jennifer Blackford, Ph.D., associate professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, examined 37 8-to-10-year-old children who either had an inhibited or uninhibited temperament.

It’s already known that children with inhibited temperament — shy, cautious, risk-adverse children — have a sevenfold risk for developing an anxiety disorder by adolescence. Given that about 15 percent of all children have an inhibited temperament, this is a significant contributor to later anxiety disorders.

By investigating both anticipation and response to images, Blackford and her team identified that even before the onset of an anxiety disorder, high-risk, inhibited children have widespread alterations in their PFC function and connectivity, characterized by an inability to proactively prepare for social threat, combined with heightened reactivity to social stimuli.

“You can actually observe this trait (inhibited temperament) in 4-month-olds,” Blackford said. “We believe it’s very biologically driven and we wanted to understand what is different in these high-risk children.”

Previous research had shown differences in multiple parts of the brain, including the prefrontal cortex, in young adults with an inhibited temperament. “But it wasn’t clear whether our findings were a cause of anxiety risk or were a consequence of years of living with an inhibited temperament.

So Blackford and other authors of the study — Jacqueline Clauss, M.D., Ph.D., (a Vanderbilt University School of Medicine student in Blackford’s lab), Margaret Benningfield, M.D., and Ulma Rao, M.D., — decided to look at children before they had anxiety; a time where they could be high risk, but had not developed an anxiety disorder.

They chose 8- to 10-year-olds because social anxiety disorders usually develop around 12 to 15 years of age. Because a core feature of anxiety disorders is excessive anticipatory anxiety, they decided to observe brain function while children anticipated seeing an aversive image.

First, children were trained to associate one colored shape with an aversive outcome (a face showing a fear expression); another colored shape with a safe outcome (face showing a neutral expression); and a third colored shape with a control condition (neutral object).

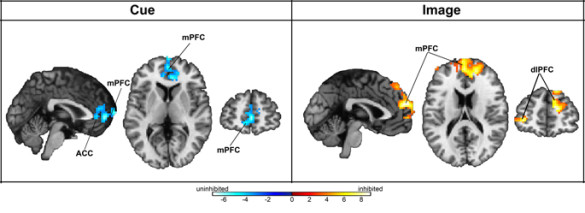

Then the children had an fMRI (functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging) scan while they were shown the different colored shape cues followed by the images.

Blackford said children anticipate fearful objects or events in different ways.

“In the real world, if your child is going to a birthday party where they know one person, the uninhibited child will tell themselves, ‘oh it’s a birthday party; it’s going to be really fun. I’m sure I’ll make new friends, and it’s always fun to eat cake.’ They view the party as something to prepare for and get excited for. The inhibited child will start to worry – ‘what if nobody likes me? What if I have to sit by myself? What if there’s a clown there? I don’t like clowns.’”

Blackford said the Vanderbilt team expected to see differences in the prefrontal cortex during anticipation, based on their studies in inhibited adults, and they did.

The uninhibited children, at low risk for anxiety, had an increase in the activation of the prefrontal cortex when they saw the cue that predicted a fear face. Once they saw the fear face, they had very little brain response, suggesting that their preparation had been successful. In contrast, the inhibited children, at high risk for anxiety, had a delayed prefrontal cortex activation.

“They weren’t able to engage the prefrontal cortex quickly during that anticipation period, but they had a robust prefrontal cortical response when they actually saw the faces. This suggests that they weren’t preparing themselves, or they tried, but the preparation was delayed.”

This study may also change the current thinking that the brain’s amygdala is the part of the brain most involved in fear circuitry, and in predicting risk of anxiety in children.

“It turns out there were no differences in amygdala function in the children at high risk for anxiety,” Blackford said. “This is shifting the paradigm completely. Instead of focusing on the fear circuitry, we need to look at the prefrontal cortex, which is what helps inhibit the fear circuit.”

The Vanderbilt team continued to follow this group of children for two years — asking the children and their parents to complete a questionnaire every six months. The additional data is currently being analyzed.

“We want to see if their brain function during this first scan can predict what happens with their anxiety,” Blackford said.

They also collected biological data, such as cortisol, a measure of stress response, in the children’s saliva.

“We’re looking to see whether there are other physiological or biological measures that help distinguish the high-risk children,” she said. “Our goal is to be able to narrow this down further with simple biological measures, like collecting saliva, so we can figure out which of these kids to focus on for prevention.”

Blackford recently spent some time in Australia meeting with researchers who have developed a preventive intervention for parents of inhibited 3-to-5-year old children.

Although more investigation is needed, the early findings show that an eight-week program for parents can significantly reduce anxiety symptoms in their children years later.

“That’s really exciting – the possibility that you could offer a short-term, affordable program to parents of high-risk children that provides them with education and support. It could have a long-term impact on the lives of these children and their families and reduce the rates of anxiety disorders.”