A GRADUATE OF VANDERBILT’S CREATIVE WRITING M.F.A. PROGRAM REFLECTS ON THE IMPORTANCE OF NURTURING LITERARY TALENT

BY MATTHEW BAKER, MFA’ 1 2

I was homeless the summer before grad school. Living on the coast of Lake Michigan in the same town where I had gone to undergrad, I was too poor even to pay rent on a $200 room.

I spent days working at a local brewery, just trying to save up enough money to buy a laptop for grad school. At night I would crash in a spare room in the basement of a sympathetic professor, or occasionally in the backseat of my car. Food-wise, I subsisted on oatmeal, yogurt, bananas, and whatever I managed to scrounge up at the brewery.

It’s probably needless to say that in choosing between creative writing programs, money was a serious factor for me. Ultimately, though, I made my grad-school decision based on something else entirely.

First of all, I didn’t have a single friend. Freakishly skinny, I wore thrift-store shirts and hand-me-down jeans that had formerly belonged to my ex-girlfriend. I was invisible to most people, and when I wasn’t invisible I wished I were. It was a small town. People would lean out the windows of cars to heckle me—sometimes teenagers, sometimes adults— shouting things that probably aren’t fit to print here. I spent the Fourth of July alone in a park reading a book by the light of a streetlamp.

I had gotten into four creative writing programs. The truth is, Vanderbilt had offered me the most money. But that wasn’t why I decided to go there. I had spent weeks on the phone talking to the faculty at the different schools. Afterward, I tried to explain to my parents why I was choosing Vanderbilt. “They didn’t just seem interested in me as a student,” I said. “They seemed interested in me as a person.”

Graduate creative writing programs in this country have a reputation for being “cutthroat,” especially the top-ranked programs. I can’t speak personally to the experience of those programs, but I’ve met a number of alumni, and I’ve heard a lot of stories.

Here’s the culture at a typical top-10 program: The atmosphere is hyper-competitive. Funding is awarded in a tiered system. Students view each other as rivals, competing for a hypothetical seven-figure book deal that looms on the horizon like the mirage of an oasis, and like any situation where millions of dollars appear to be up for grabs, things can get ugly.

One writer told me that story critiques could be so brutal in her program that it wasn’t uncommon for her to return home to her apartment and weep after having a story workshopped. Another reported incidents of students lying to each other about project deadlines and class requirements in deliberate acts of sabotage. There’s no denying that this Darwinian model produces results—Pulitzer Prizes, National Book Awards, poet laureateships—which, perhaps, is why the model is so common among top-ranked programs.

But that’s what’s remarkable about the program at Vanderbilt. Though it’s a top program, too, Vanderbilt has adopted a model that seems the very opposite of those other programs’—one that fosters a tight-knit community based on feelings of cooperation and unity.

Of course, even before a graduate program in creative writing existed at the university, Vanderbilt had a rich literary tradition, producing an especially talented batch of writers in the early 20th century, including John Crowe Ransom, a founder of New Criticism who went on to launch influential literary magazine The Kenyon Review, as well as Robert Penn Warren, who founded The Southern Review. Warren was the first poet laureate of the United States, and is the only writer ever to have won both the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry.

But there was no master of fine arts (M.F.A.) program in creative writing at Vanderbilt until 2006. Senior faculty member Mark Jarman, Centennial Professor of English, had spent 13 years working to make the M.F.A. program a reality: “Since Vanderbilt was already known as a center for Southern literature, we wanted to make it a place which encouraged young writers to enjoy that fact as a concrete thing.”

I joined what was still only the fourth class, but as young as the program was, that community model was already firmly established as the culture. In a deliberate move to preempt feelings of competition, all incoming students were awarded equal funding. Professor of English Kate Daniels, director of the program, would insist on sending all of us home with containers of leftovers after department get-togethers, as if we were her own children and she was concerned we weren’t eating enough. Novelist and Associate Professor of English Nancy Reisman brought chocolate-covered almonds to every workshop for us, carefully leading the discussion about each story up for critique, always sure to draw as much attention to its strengths as its flaws.

Poet Rick Hilles, associate professor of English, occasionally took us out for tandoori—not for any reason in particular, just to eat a meal together and chat about our lives. Peter Guralnick, writer-in-residence, whose biographies of Elvis Presley and Sam Cooke are so revered that he’s been inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame, would invite us out to singer–songwriter gigs he was interested in seeing.

That feeling I had gotten on the phone had been right: We weren’t just students to them. They cared about us as people. And although they never directly told us how to treat each other, we followed their lead. Instead of rivals, we came to see each other as allies.

Within months, looking to collaborate on a major project, we founded the national literary magazine Nashville Review. We traded writing with each other for feedback and collaborated on comics and music and gave each other tarot readings and taught each other how to roll sushi. We hosted monthly croquet tournaments in the courtyard of Sterling Court, inviting as many friends and acquaintances and neighbors and complete strangers as we could find, hoping to connect our own community with the broader community of Nashville.

This isn’t to say that our years in the program were drama- free. But rather than splintering us, any conflicts we had ultimately only made us stronger. If other programs were like joining the Hunger Games, Vanderbilt’s was like joining the X-Men.

If other programs were like joining the Hunger Games, Vanderbilt was like joining the X-Men.

To be honest, there seemed to have been something special about my class, and although this community model had worked for us, I suspected that as soon as we left, everything would probably go downhill. After a brief tenure in Ireland as a Fulbright fellow and a few years spent bouncing around between artist residencies in New York, New Hampshire and Illinois, I returned to Nashville last spring to take part in an alumni reading on campus. I was curious to see the state of the program today.

When I arrived, there was a buzz in the air: In a major coup, the program had recently recruited acclaimed writer Lorrie Moore, considered a grandmaster of the short story form, as the Gertrude Conaway Vanderbilt Professor of English. (Putting the acquisition into sports terms, Samuel Mil-ton Fleming Professor of English Tony Earley said the baseball equivalent would be a team managing to recruit Babe Ruth—adding, “Except Lorrie’s not dead.”)

Despite that latest boost in prestige for the program, the current M.F.A.s seemed as down-to-earth as ever. Anders Carlson-Wee, MFA’15, a former pro rollerblader and veteran train-hopper, offered me a futon to sleep on and made me tea and oatmeal every morning. Lee Conell, MFA’15, hung out on a hill in Sevier Park with me reminiscing about Animorphs. Carlson-Wee, William Scott Lyon and Edgar Kunz, MFA’15, took me to play bocce at Pinewood Social, talking each other through drafts of poems between throws. Alicia Brandewie, MFA’15, threw a faux prom in the clubhouse of her apartment complex, going so far as to hire a photographer so that all her classmates could have professional author photos taken, a generous gift on any grad-student budget.

But here was the moment that really struck me, a moment from my last night in town: Rita Bullwinkel, a firstyear M.F.A. from San Francisco, had invited me over for a dinner of homemade garlic bread and tortellini. After we ate, Rita brought me to Band of Poets, a monthly reading series she hosts at Bobby’s Idle Hour on Music Row. It was a fiveminute walk from her apartment to the bar, but it took us at least 15 because people at three different tables on the patio of Taco Mamacita shouted her name as we went by, all wanting to talk to her. We crossed paths with somebody at the intersection who also was happy to see her. She was friends with the owner of the bike shop we passed. When we got to the bar, which was packed, everybody there knew her, too.

Rita wasn’t just living in Nashville; she had become an active, engaged member of the city, connecting with that broader community in exactly the same way my class had through those games of croquet. With a sense of excitement, watching Rita and the other M.F.A.s chat with people in the crowd, I finally realized my class hadn’t been special—or that maybe my class had been special, but that every class in our program was going to be special in that same way.

The program at Vanderbilt is still only nine years old. In that sense it’s a prodigy, because the community model is already producing tangible results. The program has an embarrassment of riches: Current M.F.A. student Tiana Clark won this year’s Rattle Poetry Prize, a $10,000 award for a single poem. Edgar Kunz is currently a Stegner fellow at Stanford University, regarded to have the most prestigious postgraduate creative writing fellowship in the country. Anders Carlson- Wee recently was selected as a National Endowment for the Arts fellow, an achievement that’s almost unheard of for a writer so early in his career.

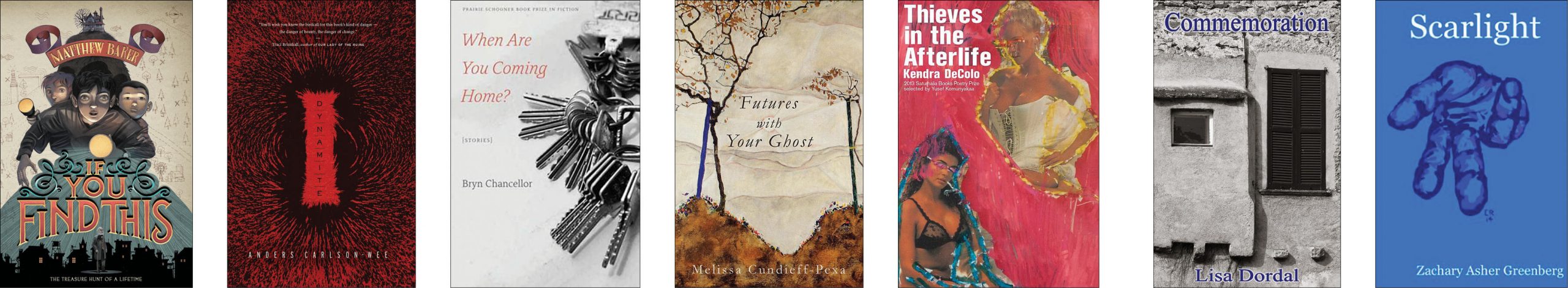

The debut collection by Kendra DeColo, MFA’11, Thieves in the Afterlife, won the Saturnalia Books Poetry Prize. The debut collection by Bryn Chancellor, MFA’09, When Are You Coming Home?, won the Prairie Schooner Book Prize. Carlson- Wee’s debut chapbook, Dynamite, won the Frost Place Chapbook Competition. Zachary Greenberg, MFA’12, published the collection Scarlight; Lisa Dordal, MDiv’05, MFA’11, published the chapbook Commemoration; and Melissa Cundieff-Pexa, MFA’12, published the chapbook Futures with Your Ghost. Janet Thielke, MFA’13, has spent the past few years serving as writer-in-residence at institutions across the nation, including the Wisconsin Institute for Creative Writing, the Stone Court Program and Colgate University.

This past summer I landed a fellowship to the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, admission to which is notoriously competitive. On the walking tour of the University of the South campus, I met a poet from another top program. “Where’d you do your M.F.A.?” he asked. “Vanderbilt,” I said. Shaking his head, the poet gave a quiet laugh, as if in disbelief. “What?” I said. “There’s just so many of you here,” he said. (Apparently, he had already met the other six Vanderbilt writers who were also there.)

In some ways my situation hasn’t changed much from that summer before grad school. I’m living back on the coast of Lake Michigan, and for a 30-year-old, I’m relatively poor. I have an apartment now, but no car. I subsist mainly on rice, lentils and bananas. My glasses are held together by tape. Walking home from the grocery store recently, the heels fell off both of my shoes. Turns out there’s some truth to that starving-artist cliché.

But to be honest, that was always part of the allure for me. I liked the idea that making a living as a writer would be a challenge. And this time things are different. I’m not alone anymore.

Matthew Baker is the author of If You Find This (2015; Little, Brown), which is nominated for a 2016 Edgar Award and was named a Booklist Top Ten Debut of 2015. His stories have appeared in publications such as American Short Fiction, New England Review, One Story, Electric Literature, and Best of the Net. A recipient of fellowships from the Fulbright Commission, the MacDowell Colony, and the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, he was the founding editor of Nashville Review.

A Good Story to Tell

—RYAN UNDERWOOD

Throughout the 1920s, Vanderbilt emerged as one of the preeminent centers for American literary thought, cultivating such influential voices as Robert Penn Warren, BA’25, Pulitzer Prize winner and the nation’s first poet laureate; critic John Crowe Ransom, a 1909 alumnus and English department faculty member from 1914 to 1937; and poet Allen Tate, BA’22, a contemporary of T.S. Eliot and Ernest Hemingway.

By 1922 a band of writers who had been working together at Vanderbilt launched The Fugitive, a journal of poetry and criticism that sought to portray the South as more economically and intellectually vibrant than critics claimed. Though it published only for three years, The Fugitive was highly influential and led to a seminal (and controversial) collection of essays five years later defending Southern culture titled I’ll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition.

A few other revered literary figures who either graduated from or studied at Vanderbilt include Pulitzer Prize-winning author Peter Taylor, who attended in 1936–37 but left to study with Ransom at Kenyon College; Elizabeth Spencer, MA’43, winner of the PEN/Malamud Prize and five O. Henry Awards; poet and novelist James Dickey, BA’49, MA’50, best known for Deliverance; and National Book Award winner Ellen Gilchrist, who attended in 1953–54.

Today, Vanderbilt continues to build its literary reputation. In 2013, the acclaimed short-story writer and novelist Lorrie Moore joined Vanderbilt’s English department faculty as Gertrude Conaway Vanderbilt Professor of English. Other notable faculty members in the department include writers Tony Earley, Lorraine López and Nancy Reisman, as well as poets Kate Daniels and Mark Jarman. In 2006, Vanderbilt launched a master’s degree program in creative writing, which accepts just six students a year—three in fiction, three in poetry. The two-year program already has been recognized as one of the top 15 programs in the U.S. and, with its small class size, the most selective.

I was homeless the summer before grad school. Living on the coast of Lake Michigan in the same town where I had gone to undergrad, I was too poor even to pay rent on a $200 room.

I was homeless the summer before grad school. Living on the coast of Lake Michigan in the same town where I had gone to undergrad, I was too poor even to pay rent on a $200 room.