The stirring “Santa Claus Symphony” would be perfect for the annual holiday season. Another composition summons the grandeur and beauty of Niagara Falls. A third symphony anticipates jazz by 50 years.

Unfortunately, very few – close to zero – living classical music fans have heard these works. That’s because they were written in the 19th century by American composers and rarely performed by orchestras of the time, who preferred to play it safe with Brahms, Beethoven and other European masters. The works were nearly forgotten until a Vanderbilt University musicologist became determined to rescue them.

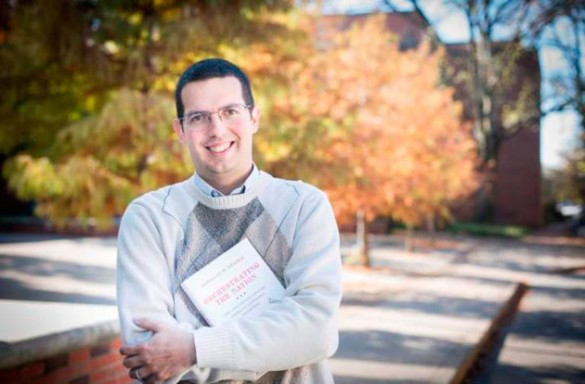

“Audiences and music lovers today believe that Connecticut native Charles Ives (1874-1954) was one of the very first to write in an eclectic way, and they call that eclecticism American,” says Douglas W. Shadle of Vanderbilt University.

“But in reality, there were many composers who earlier incorporated different elements from the American soundscape and didn’t get credit for it,” he says.

Shadle, assistant professor of musicology at Blair School of Music at Vanderbilt, has been studying about 50 American composers active in the 1800s. They are the subject of his new book, Orchestrating the Nation: The Nineteenth-Century American Symphonic Enterprise (Oxford University Press).

Shadle, assistant professor of musicology at Blair School of Music at Vanderbilt, has been studying about 50 American composers active in the 1800s. They are the subject of his new book, Orchestrating the Nation: The Nineteenth-Century American Symphonic Enterprise (Oxford University Press).

Early American orchestras, such as the New York Philharmonic, were originally designed to support local composers. But they often neglected this mission.

“There were revolutions in Europe, and many of those revolutions failed,” Shadle says. “A lot of the revolutionaries moved to the United States thinking it would be a place more open to their political ideas.”

Some of them were musicians, and most preferred the music they remembered from home.

“Germans started to populate orchestras in very high percentages,” Shadle says. “Once they achieved a majority, there was this mission creep in the orchestras to extend German culture in the United States. Then later in the century, critics tended to be anti-American in their disposition and very conservative in their tastes.”

Those circumstances led to composers like Brooklyn, New York-born George Frederick Bristow (1825-1898), Boston’s Amy Beach (1867-1944), and Philadelphia native William Henry Fry (1813-1864) having to struggle to convince orchestras to perform their works. They occasionally managed a debut performance of a new piece but rarely a second or third.

“This music deserves a second listen,” Shadle says. “It’s really entertaining to encounter it. It’s a story people don’t know, and it’s valuable to be able to give voice to people who were suppressed.”

Consider “A Night in the Tropics,” written in 1859 by Louis Moreau Gottschalk.

“He wrote it for a big festival in Havana and hired an Afro-Cuban drumming ensemble to be part of the orchestra,” Shadle says. “It’s a very early example of cultural hybridity with standard European orchestra and this vernacular folk tradition.

“The music in many ways sounds like jazz in terms of its rhythmic profile and melodic gestures. You listen to it today and it’s hard to believe that it was written 50 years before we even think of the bubbling up of jazz,” he says.

Gottschalk (1829-1869), a French Creole from New Orleans, became famous throughout the United States as a piano soloist but had to go to South America to find audiences for his symphonies. His contemporary Bristow was better positioned to have his music heard, as he played violin in the New York Philharmonic for 40 years.

“His career as a composer rose and fell based on who the conductor of the New York Philharmonic was,” Shadle says. “If there was not a sympathetic conductor, then he had a lot of trouble.”

Beach was the first successful American female composer. The Henniker, New Hampshire, native did not have to make a profit on compositions such as “Gaelic.”

“She was at somewhat of an advantage,” Shadle says. “She married a wealthy man who was able to finance her career. She didn’t have to worry whether her compositions were going to bring in money.”

Bristow’s “Niagara Symphony” was his masterpiece, finished in 1893. It was finally performed five years later, shortly before Bristow’s death.

“The most awesome component is the fourth movement,” Shadle says. “By the end, the full orchestra is just banging out this majestic C major chord, and the whole idea is that the audience would be overwhelmed by the sound of the music, just like you are if you are at Niagara Falls.”

No recording of “Niagara Symphony” exists.

“It is truly a magnificent and remarkable piece and just a crowning achievement for this set of composers across the century,” Shadle says. “There’s not even a critical edition that scholars have put together. That may be a future project of mine, to have it performed.”