Counterintuitive findings reveal how race shapes the immigrant experience and the impact of education on employment outcomes for certain groups

In the United States, black immigrants are more likely to both be in the labor force and working than blacks born in the U.S.—but a college degree erases that difference, according to a surprising new analysis [abstract only] presented at the Population Association of America’s 2015 meeting by Vanderbilt Professor of Sociology Katharine Donato and graduate students Anna Jacobs and Brittany Hearne.

This is the first time researchers have examined how the interactions between race and nativity status affect employment outcomes, and Donato says the findings reveal a “real blind spot” for migration researchers. Up until now, research on nativity status and employment outcomes had been race-blind—and those prior findings could not have been more different.

Using detailed demographic data, the researchers examined the employment outcomes of nearly 150,000 unincarcerated men and women aged 18-54, both U.S.- and foreign-born, who identified themselves as black.

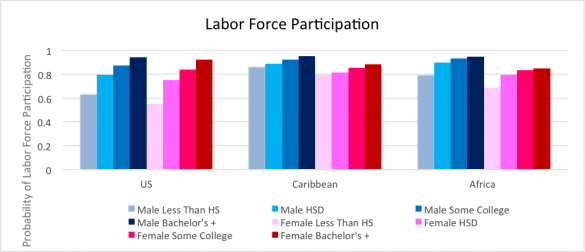

The researchers first looked at how many of these individuals were in the labor force—either working or seeking work. (This excludes everyone not in the labor force such as those with disabilities, full-time homemakers, etc.) They found that a higher proportion of immigrant blacks were likely to be members of the labor force than U.S.-born blacks.

Prior race-blind analyses showed that immigrants were less likely to be in the labor force than their native-born counterparts.

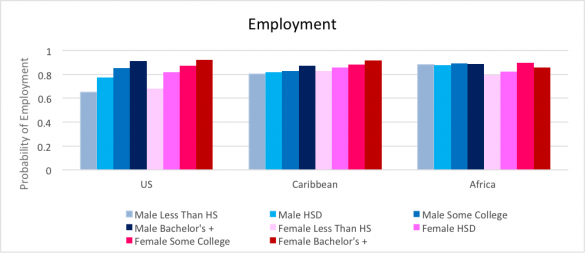

Then they looked at how many members of the labor force were employed for each group. Here too they found that, among all blacks seeking work, U.S.-born blacks had worse chances of being employed than immigrant blacks. Additionally, they found that, among all foreign-born blacks seeking work, the men had worse chances of being employed than the women.

Again, prior race-blind research showed the opposite: that the native-born had a better chance of being employed than their foreign-born counterparts, and that immigrant women were the least likely to be employed of all. But when the field is narrowed down to only black respondents “we don’t see immigration or [female] gender disadvantaging blacks at all,” Donato says.

Finally, Donato and her team looked at educational attainment levels for both groups. They found that U.S.-born blacks with college degrees had the same odds of being in the labor force and employed as foreign born, college-educated blacks. “When we add in education in this more nuanced, rigorous way, we actually find that education really neutralizes this disadvantage.”

“So, in two ways this analysis provided insights that we didn’t know before,” Donato says. The first surprise was that the immigration disadvantage seen in the general population is reversed for blacks. But the research also revealed, with unusual clarity, a mechanism by which that disparity could be addressed: education.

“[rquote]It’s rare as a social scientist that you get to do an analysis that really speaks to policy as clearly as this one[/rquote],” Donato says. “When we think about areas of inequality that policy can help us alleviate, we can make policies that encourage college enrollment and college completion. We can do something about education.”