Though it is often hailed as a potentially miraculous cure for obesity or diabetes, very little is known about brown adipose tissue, or “brown fat.”

Vanderbilt University Medical Center researchers received a $2.15 million grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to study the amount and activity of brown adipose tissue in adult humans, a critical step in understanding its role in metabolic disease and finding therapeutic targets.

Once believed to be found only in human infants, rodents or hibernating animals like bears and squirrels, brown adipose tissue is actually present around the shoulders, and possibly the kidneys, in adult humans. Unlike white fat (the jiggly fat that increases body mass), which stores energy, brown fat is designed to generate heat.

“There have been high hopes for a weight loss cure and some fascinating implications with diabetes, but we really haven’t been able to understand what brown adipose tissue does and how it does it,” said Brian Welch, Ph.D., MBA, assistant professor of Radiology and Radiological Sciences.

“We think our study will set the stage for future longitudinal studies of interventions to increase the amount of brown fat or just stimulate what is already there.”

Welch and Theodore Towse, Ph.D., assistant professor of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, are primary investigators on the five-year study, which will recruit about 150 subjects into three different areas — investigating the impact of physical activity and gender, age and body composition and diabetes on brown adipose tissue mass.

“I have a feeling we’re going to see less brown adipose tissue in obese subjects, and I expect it to be not as easily activated. But if it turns out the other way, that would be really interesting too. We have some ideas based on existing literature in animals, but we need more in humans,” Towse said.

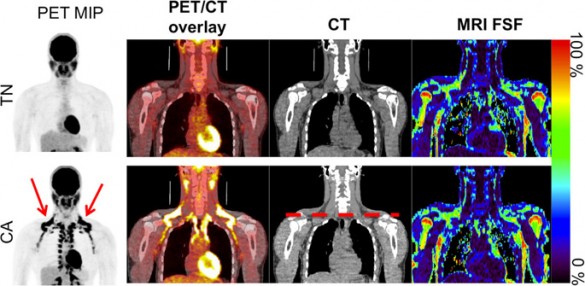

An important innovation in this study is the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) instead of positron emission tomography (PET). PET uses a radioactive glucose molecule to detect the brown fat, and subjects usually have to be scanned after exposure to cold temperatures.

“One really important drawback of the PET method, besides that it is reactive and the people are cold, is that the brown fat may not take up the tracer. It has to be activated and wanting to use fuel, and the fuel that it uses most of the time is fat. It will burn sugar, but it’s not as preferred,” said Welch, who validated the MRI techniques in a previous study.

MRI is much safer, more reliable, costs less and works at normal room temperature.

“Temperature is important because a person may not activate with the cold but we could still see and know that they have brown adipose tissue,” Towse said.

“If they have it but it doesn’t activate, that’s interesting to the physiologist. They might be perfectly healthy and it doesn’t activate, or they may be overweight and diabetic. There are a lot of questions still to be answered about that.”

Subjects will be both male and female and have a range of ages and body compositions. Some of the study aims will manipulate temperature and evaluate how brown adipose tissue reacts, while others will see what happens after the subject is fed a meal.

This study is a collaboration between Vanderbilt’s Departments of Radiology and Radiological Sciences and Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. It is the first major grant for PM&R since its establishment in 2012.

“We’re not really sure what brown adipose tissue means for rehabilitation. People with severe burns have an upregulation in it, and there seems to be a drop with aging. There appears to be communication between muscle and brown adipose tissue, which may provide us with an understanding of muscle wasting,” Towse said.

“What I learned in my undergraduate physiology classes was that there wasn’t any brown adipose tissue in adults. So we have come a long way, but still have much to learn.”

The research is supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01DK105371.