By Mary Anne Hunting, BA’80

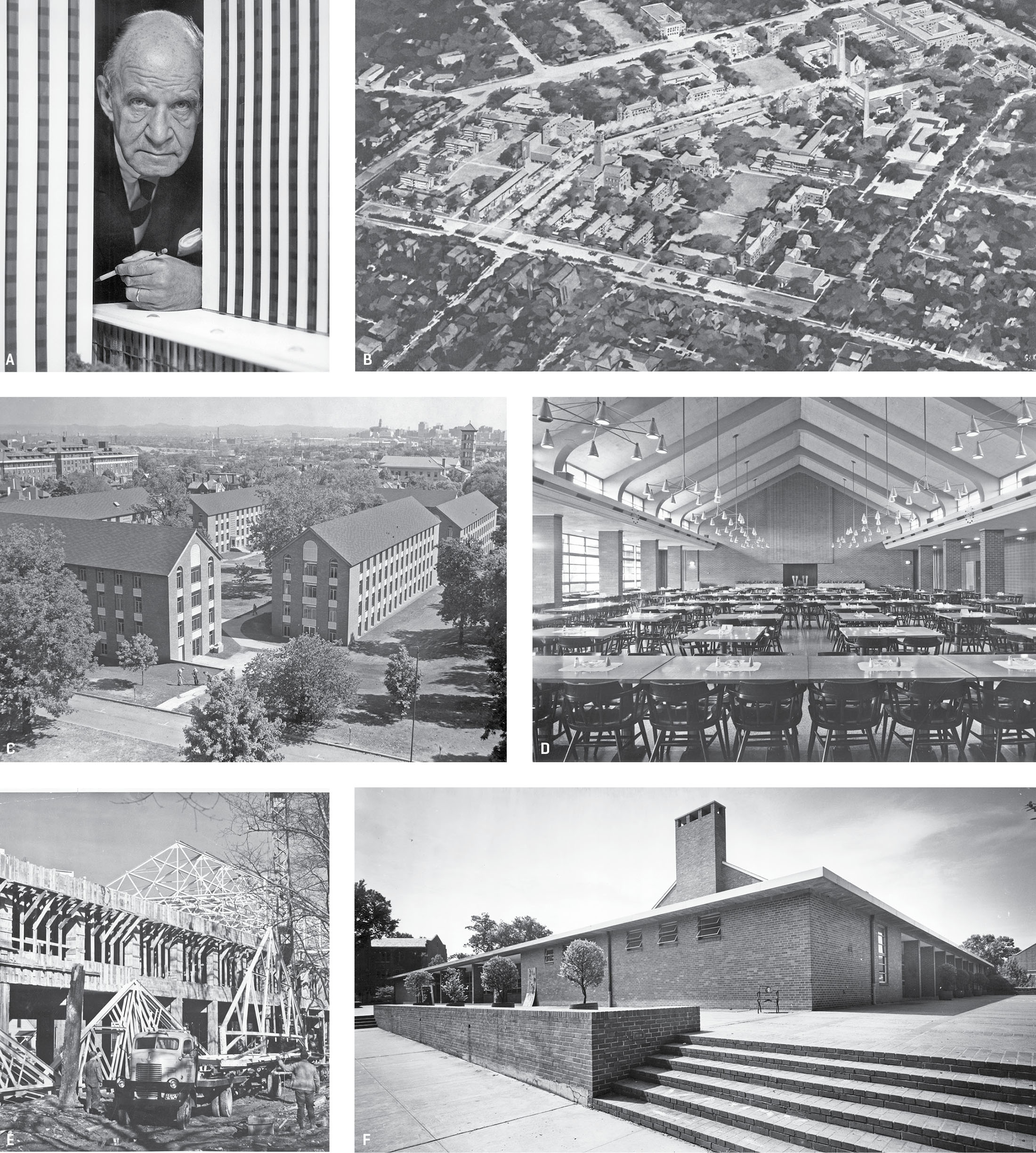

I had no idea when I chose architect Edward Durell Stone (1902–1978) as the subject of my Ph.D. dissertation—later published as a book—that the young architect from Arkansas had created a seminal campus plan for my own alma mater in 1946. During the next decade he served as Vanderbilt University’s consulting and supervising architect before achieving world fame with his American Embassy in New Delhi (1959) and United States Pavilion at the Exposition Universelle et Internationale 1958 in Brussels.

Nor could I have known that my dissertation adviser and mentor at the City University of New York, Kevin D. Murphy, would later join the Vanderbilt faculty as the Andrew W. Mellon Professor of Humanities. Only after accepting Kevin’s invitation to lecture during Reunion and Homecoming last fall did I dig deep into the archives and was dumbfounded to discover just how pervasive Stone’s imprint is on the Vanderbilt University campus.

It was Harvie Branscomb, I learned, who insisted that Stone be the “final authority” on all matters of planning and design during that era. After Branscomb became Vanderbilt’s fourth chancellor in 1946, one of his most pressing tasks was to determine the placement of a new engineering building (completed in 1950, now part of Featheringill–Jacobs Hall). The chancellor quickly realized he could not consider this building in isolation from other much-needed building projects. Moreover, he learned that campus development was still bound by a master plan created in 1924 by the late Charles Zeller Klauder, a Philadelphia architect who never even visited Vanderbilt.

As Branscomb contemplated the challenging issue of expansion, he became increasingly concerned that his vision of the university as a major national private institution could be choked by limitations of its site. The campus was hemmed in by two traffic arteries and urban deterioration, badly located buildings, and insufficient acreage for growth—only about 79 acres, as opposed to today’s 330.

Compounding the challenge were a woefully short supply of housing, an unsavory dining facility in the basement of Kissam Hall dormitory (built in 1901 and demolished in 1958), acute automobile congestion, and inadequate quarters for the professional schools. (The law school, for example, was located on the upper two floors of Kirkland Hall.)

Although Branscomb considered the idea of relocating the university some 10 miles outside Nashville, he deemed it more beneficial to stay close to the medical school. And so, he proposed to the Board of Trust that an architect of national stature be engaged immediately to prepare a plan for development that also would include a recommendation about how to harmonize the buildings stylistically.

Fortuitously for Stone, Branscomb approached Howard Meyers, publisher of Architectural Forum and a great Stone supporter, for a list of architectural firms. Stone sold himself over another New York City firm—Voorhees, Walker, Foley and Smith—because of his diverse experience and the small size of his office, which would allow him to devote more personal attention to Vanderbilt.

Stone’s most illustrious commission to date had been co-design of the Museum of Modern Art building (1939) in New York City, America’s first building designed in the International Style. Branscomb, however, undoubtedly was more attracted to Stone’s wartime large-scale, long-range planning for the Army Air Force, as well as his familiarity with collegiate building that came with experience as an instructor of advanced design at Yale University. It also probably helped that Stone had worked on Vanderbilt’s medical school building in 1924 as a novice draftsman with Coolidge, Shepley, Bulfinch and Abbott in Boston.

NECESSARY BUT INCIDENTAL

Although Branscomb eventually recognized Stone as “one of the great architects of our generation,” to the chancellor architecture was utilitarian—“necessary but incidental.” This is what he wanted from Stone—even though the architect was capable of so much more.

The campus master plan totally fulfilled Branscomb’s expectations. Bold in conception, it broke the psychological barriers that could have precluded his expansion program. While some aspects were at first greeted with criticism—a new formal entrance (1949) with a double drive in front of Kirkland Hall, for example—Branscomb did not veer from the plan that, in his opinion, brought great satisfaction.

Much of the tranquil beauty that imbues today’s campus was engendered by the Stone plan. All new buildings were grouped properly by function around gracious quadrangles and, most important, faced inward toward the campus. Automobile traffic was removed to the periphery, and ample pedestrian pathways were fixed in its place. The overall aesthetic honored established traditions of native red brickwork, albeit with less of the superficial decorative detail of the prevailing collegiate Gothic.

Branscomb was impressed with Stone’s careful and thorough methodology and found him easy to work with. In July 1947 he told the architect he wanted to continue their happy and profitable relationship, charging him with overseeing site improvements as well as new building locations and construction by numerous local architects. He corresponded frequently with Stone, seeking direction and advice, reassurance and appeasement. Branscomb encouraged the Buildings and Grounds Department to do the same: “I want to get everybody around here in the habit of referring to you any major changes, rather than relying upon our own inexpert opinions,” he wrote to Stone in March 1949.

The chancellor initially had no intention of hiring Stone to design any of the buildings, but because Stone progressively became more involved with each project, in 1950 his contract was expanded to include design services.

The proposed engineering building, the first to require Stone’s attention as consulting architect, was to be designed by Hart, Freeland and Roberts. Branscomb was so dissatisfied with the firm’s preliminary drawings, though, that he insisted they be sent to Stone for his review—which, in retrospect, set a precedent. Stone made numerous recommendations and changes, including the addition of brick pointed arches and stone window surrounds on the front façade.

In a similar vein, when the Building Committee was not too pleased with the scheme presented by Edwin A. Keeble, architect of the new gymnasium (1952), Branscomb asked Stone for a basic plan and exterior elevation, which, Branscomb recollected, was fantastically drawn with simplicity and beauty.

Stone also re-evaluated the 1945 plan for a grouping of seven dormitories, of which only two—McGill and Tolman, both designed by Francis B. Warfied and Associates—were actually built because of wartime shortages. Stone’s study included plans, elevations and color perspectives of three buildings as well as a model and details of a typical student room. Cole Hall (1948) grew out of this study, as did Vanderbilt and Barnard halls (1952), organized as one building parallel to West End Avenue, all of them again designed by Warfield.

Branscomb was resolute in his view that, despite construction of these dormitories, Vanderbilt gradually would go out of business as a residential college if an adequate dining hall were not erected. No other building, he informed the board, would benefit the campus as much.

Warfield was apprehensive—with good reason, as it turned out—about submitting his preliminary studies to Stone’s office in New York City, as Branscomb required him to do. Stone immediately questioned whether some of Warfield’s assumptions would impose unnecessary limitations. Consequently, Stone suggested, and Branscomb agreed, that he take control of design development for the dining hall by providing complete floor plans, elevations, exterior and interior perspectives, layouts, and furnishing plans.

Although Warfield would still be credited as the architect of record, he would be responsible only for the working drawings, specifications and supervision of construction—not the design.

RENDEZVOUS AT THE WALL

As built, Rand Hall (1953) demonstrated Stone’s ability to combine seemingly unrelated functions—dining facilities, bookstore and post office—into a cohesive scheme. It further showed his enthusiasm for imposing building forms with clean, simple details as well as grand, majestic interior spaces with commanding views of the outside environment. Most of all, it encouraged students and faculty alike to rendezvous—along the venerated “wall” on the east terrace, for example.

Stone also contributed to the remodeling of Neely Auditorium (1951), the design of a small chapel (1951) in memory of Kate Douglas Stockham in Wesley Hall, and preliminary schemes for Branscomb Quadrangle (1962).

But he was most pleased with his plans for the Medical Arts Building (1955), located on 21st Avenue South at Garland Avenue. After reminding Branscomb that he could be of more value if his services were used from the inception of a project, Stone was invited to present preliminary sketches for Medical Arts, a building of “good but not deluxe construction”—even though the firm of Marr and Holman was already on board as the local architect. The brick patterning still embellishing the north and south façades expressed Stone’s penchant for geometric decoration and foretold the aesthetic that would bring him worldwide attention soon afterward.

During construction, however, Stone was in Europe for a time, leaving the local architects to struggle with revisions and contributing to Branscomb’s rising concern that Stone was becoming less accessible.

Even so, Branscomb conceded in 1955 when Stone zealously went after the Kissam Quadrangle (1957) commission, not necessarily out of his loyalty to Branscomb but because it was also his most important job prospective and would be his “bread and butter” for the next six months.

Although the group of six dormitories would be Stone’s only buildings at Vanderbilt stamped solely with his name, there was no end of troubles with this $2 million project—largely because at the same time, Stone was situated in Palo Alto, California, constructing the Stanford University Medical Center (1959).

Kissam Quadrangle had evolved from the question of whether to follow through on the Board of Trust’s decree from 10 years earlier that Kissam Hall, a five-story dormitory on the south end of what is today’s Alumni Lawn, be demolished. Upon determining that a renovation could cost up to $1.8 million, it was decided to replace the dormitory with new ones—just north of Warfield’s Vanderbilt and Barnard halls.

Stone insisted that the board’s decision to duplicate these two dormitories for the new ones would be unsightly because of the sloping terrain of the designated location. Instead, he proposed a scheme predicated on one of his favorite architectural compositions: Thomas Jefferson’s “Academical Village” at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, where regularly spaced buildings are unified by walls and colonnades.

But the trustees did not buy into the plan—which consisted of three-story units of 100 rooms, each aligned at right angles to West End Avenue and connected by a one-and-a-half-story recreation and administration building—primarily because the rooms would have looked onto each other instead of the campus, the centerpiece of Stone’s master plan.

At this point Harold Stirling Vanderbilt—great-grandson of Cornelius, generous donor, newly appointed board president, and eager Building Committee member—began to involve himself personally in the planning. Stone provided a pleasing alternative to Harold Vanderbilt’s scheme, which, he hoped, would resolve his criticisms.

But well into the working drawing phase in early 1956, Vanderbilt was calling for changes in the location of facilities, size of buildings and exterior appearances. Unwarranted changes undoubtedly were made.

MODERN COLOSSUS

Stone would go on to achieve unprecedented, widespread international appeal with a distinct modern aesthetic of enrichment and decoration that, in the opinion of many, revitalized Modernism. With buildings still represented on four continents, in 13 foreign countries and in 32 states, the diversity and scope of his contributions have no bounds. Indeed, at his peak Stone was considered a “colossus,” a “visionary” and a “giant.”

Kissam Quadrangle was demolished in 2012. In its place the two newest residential colleges, Warren and Moore, opened to students in August.

With this information in hand, take a moment to look around next time you visit the campus. You will see that the Stone signature, the culmination of a perspicacious collaboration with a farsighted chancellor, still pervades the Vanderbilt campus—everywhere.

Mary Anne Hunting is an architectural historian and author of Edward Durell Stone: Modernism’s Populist Architect (2013, W.W. Norton). She thanks Evan Jehl, BA’14, for his research assistance in writing this article.