A renowned New Testament scholar at Vanderbilt University who studies Jesus’ first-century context has found that his parables, when heard in their own historical setting, have surprising messages that speak to readers 2,000 years later.

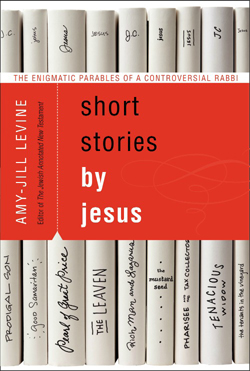

Amy-Jill Levine, University Professor of New Testament and Jewish Studies, is the author of Short Stories by Jesus: The Enigmatic Parables of a Controversial Rabbi (HarperOne, 2014).

Levine, who is also the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Professor of New Testament Studies and professor of Jewish Studies in the Divinity School and College of Arts and Science, will discuss and sign copies of her new book at Barnes & Noble at Vanderbilt Tuesday, Sept. 9, from 7 to 8 p.m.

“Down through the centuries, starting with the Gospel writers themselves, the parables have been allegorized, moralized and otherwise tamed into platitudes such as ‘God loves us’ or ‘be nice.'” Levine said. “[rquote]If we stop with the easy lessons, good though they may be, we lose the way Jesus’ first followers would have heard the parables, and we lose the genius of Jesus’ teaching.”[/rquote]

Levine’s concern is not to dismiss interpretations that have developed over the centuries. It is, rather, to hear the parables anew in their own historical contexts and then to see how those original messages might still have value.

“Too often we settle for the easy interpretations: We will be forgiven, as was the prodigal son; we should pray and not lose heart, like the importuning widow,” she said. “When we seek assurances from parables, a genre that is designed to surprise, challenge or indict, we are necessarily limiting their teaching.”

One of Levine’s reasons for writing Short Stories by Jesus was to correct the misunderstandings some readers have of Jesus’ Jewish context. “Some of my chapters serve as a corrective to the interpretations made by clergy who know little or nothing about early Judaism,” she said. “For example, parables about women are sometimes seen to challenge Jewish misogyny. Instead, given the prominent role of women in Jewish scriptures as well as their general independence in early Jewish society, it would be odd were Jesus not to tell stories about women. Or, the father of the ‘Prodigal Son,’ usually understood as a symbol for God, is seen as surprising because he welcomes his dissolute son home. There is no surprise here either; Jewish sources are filled with accounts of God’s welcoming the sinner.”

Levine notes that common interpretations of the “Parable of the Good Samaritan” are often misleading. In the biblical story, a person traveling from Jerusalem to Jericho is beaten, robbed and left for dead on the side of the road. A priest and a Levite both ignore the victim, but a Samaritan has compassion and cares for him.

Levine notes that common interpretations of the “Parable of the Good Samaritan” are often misleading. In the biblical story, a person traveling from Jerusalem to Jericho is beaten, robbed and left for dead on the side of the road. A priest and a Levite both ignore the victim, but a Samaritan has compassion and cares for him.

“It is not uncommon to hear that the reason the priest and Levite walked by is because they are afraid they’ll become ritually impure if they touch him,” she said. “The parable has nothing to do with purity issues, and the two men have no excuse. Then, we hear that the Samaritans were oppressed by Jews, and so the Samaritan becomes compared to people oppressed in our own society. Again, the reading is wrong, for Samaritans were not a minority oppressed by Jews. Unless we understand why Jesus mentioned a priest and a Levite, and not just two otherwise unknown people, we will never understand the parable’s challenge. Unless we understand first-century Samaritan/Jewish relations, we will miss the punch of the parable. And if we consider where Samaria is today, we might be able to hear the parable in all its profundity.”

Other parables that Levine analyzes in their first-century context include “The Mustard Seed,” “The Rich Man and Lazarus,” “The Lost Sheep and the Lost Coin,” “The Pearl of Great Price,” “The Laborers in the Vineyard,” and “The Pharisee and the Tax Collector.” In each case, she shows how first-century listeners might have understood the parables.

Levine emphasized that one does not need to be Christian for Jesus’ narratives to inform, challenge and even provoke any of us to explore our values and beliefs. She describes the parables as pearls of Jewish wisdom. “They should tap into our memories, our values and our deepest longings. The more I study the parables, the more I am challenged by them.”