A Punch in the Nose Takes Down the World’s Most Dangerous Animal

Professor Laurence Zwiebel has spent years trying to get inside the mind of a killer. “It’s a know-your-enemy sort of thing,” he explains.

In this regard he’s much like a detective, only the killer he’s pursuing is nearly everywhere at once—on every single continent, save Antarctica. And it’s not so much the killer’s mind he’s trying to get inside of, as it is its nose.

“The mosquito perceives the world largely through its nose,” says Zwiebel, the Cornelius Vanderbilt Professor of Biological Sciences and professor of pharmacology. “It has developed parallel pathways to take in various chemosensory stimuli—what we call ‘odor space.’ When it’s looking for a blood meal, it shifts its olfactory system toward a particular set of stimuli—meaning us.”

The insectary on Vanderbilt’s campus, where he and other vector biologists do their research, is home to thousands of Anopheles gambiae, the species of mosquito most responsible for the spread of malaria in sub-Saharan Africa. None of the Vanderbilt mosquitoes is infected with the pathogen, but that doesn’t make them any less bloodthirsty.

“The most salient characteristic of the Anopheles gambiae—and the reason it’s the most dangerous animal on the planet—is that it bites only humans if it has a choice,” he says.

Zwiebel’s research, which is supported by an $11 million grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and more than $5 million in grant funds from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), focuses on preventing mosquitoes from feeding on humans. Specifically, he targets the insect’s olfactory system to alter its behavior. Here he explains just how this is accomplished and what it means for the future of mosquito repellents.

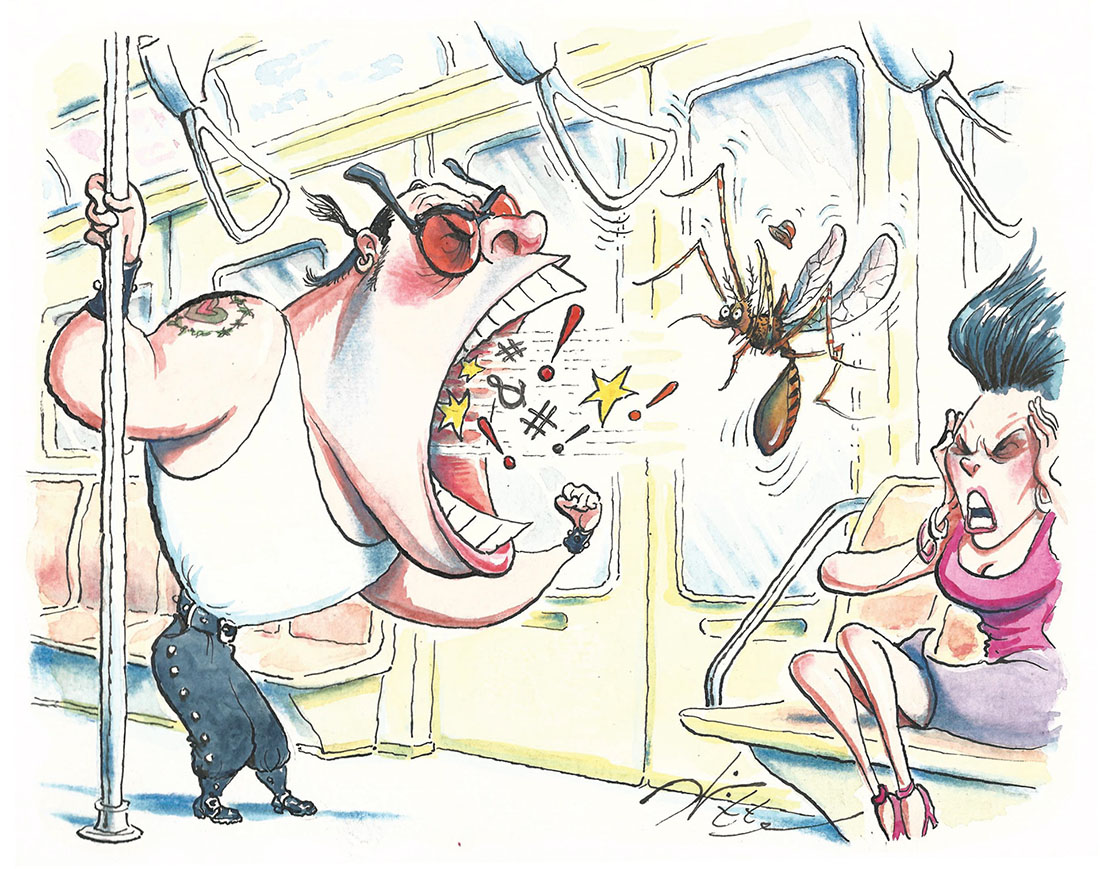

» Unlike DEET and other traditional repellents that block a mosquito’s ability to smell, Zwiebel’s approach works through overstimulation and is potentially thousands of times more powerful. “We’re not looking to block odor receptors but rather turn them all on at once. It’s what we call excito-repellency. IT’S SOMETHING LIKE THIS!” he says, driving the point home by shouting. “See what I mean? I refer to it as ‘the New York style of repellency.’ I grew up in a city where you had to be pretty obnoxious to get somebody to go away.”

» Partnering with the Vanderbilt Institute of Chemical Biology, Zwiebel’s team used high-throughput screening to target an olfactory co-receptor shared not only by mosquitoes but by all insects. The discovery means this type of excito-repellency could have applications in agriculture and other pest-control scenarios. “It takes roughly $250 million to turn an idea like this into a viable product,” Zwiebel says. “A repellent just for mosquitoes, no matter how effective it is, doesn’t warrant that kind of gamble, but the fact that it could be used on all insects changes everything.”

» The excito-repellent could take different forms, from a traditional volatile spray to something that could be impregnated into clothing or paints. Whatever the end product, great care must be taken to avoid interfering with the balance of nature. “This is not a story about insecticide. We’re not interested in eradicating mosquitoes or other insects,” Zwiebel says. “Mosquitoes are entitled to have blood meals and happy, productive lives—just not at the expense of humans.”

TEXT BY SETH ROBERTSON

See inside Vanderbilt’s insectary, and learn more about Zwiebel’s research: