Manuscript’s Clues Reveal a Story within a Story

No one was more surprised by his findings than Gregg Hecimovich, MA’93, PhD’97. A longtime fan of literary puzzles—he wrote his dissertation about riddles in Keats, Joyce and Dickens—he perhaps should have expected a twist.

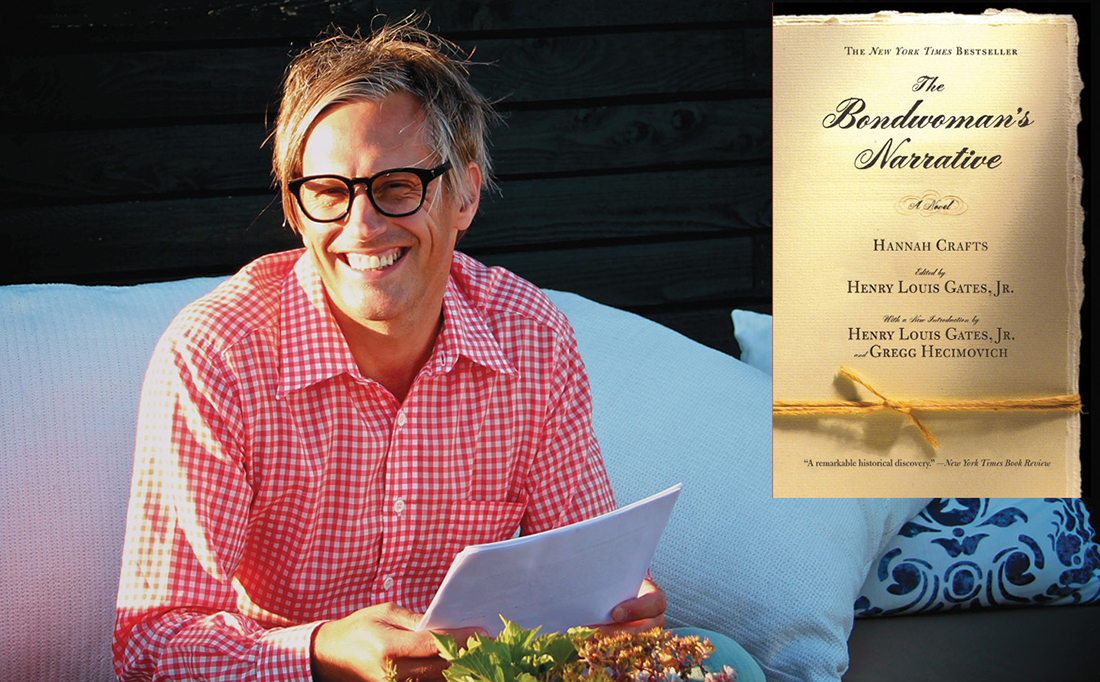

Hecimovich, chair of the English department at Winthrop University in Rock Hill, S.C., began searching a decade ago for clues to the true identity of Hannah Crafts, author of The Bondwoman’s Narrative. The 1850s manuscript, which was acquired by literary critic and scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. in 2001 and became a best-seller the next year, posed a grand literary mystery: Who had written this compelling story about a house slave who escaped to freedom?

Gates believed it was a semi-autobiographical tale written by a former slave, the first of its kind ever found. Some academic observers, however, including Hecimovich, then an English professor and associate dean at East Carolina University, were skeptical. They doubted a recently escaped slave would have had the opportunity to acquire the literacy skills needed to write the novel, especially given its many allusions to 19th-century classics such as Charles Dickens’ Bleak House and Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre.

“Originally I thought the writer was a niece of [John Hill] Wheeler’s,” Hecimovich says, referring to the North Carolina politician and slaveholder whose fictionalized counterpart comes to own Hannah in the novel. Hecimovich’s research, through university archives, public records, interviews and private papers long hidden in local attics, debunked his first theory and eliminated subsequent suspects, too.

Now, in the introduction to the new edition of The Bondwoman’s Narrative, due for release in March, Hecimovich identifies Hannah Crafts as Hannah Bond, a slave to the Wheeler family until escaping in the 1850s.

“Once I started digging into the history, the scales fell from my eyes,” Hecimovich says. Among other things, he found that the Wheelers used literate slaves to perform secretarial work, such as correspondence. He also realized that the echoes of popular novels in Bond’s writing make perfect sense.

“The act of acquiring literacy is almost always self-taught, and involves a parroting of what one is learning from,” Hecimovich says. Bond learned from the literature read and recited in the Wheeler house.

Hecimovich will share his full findings in The Life and Times of Hannah Crafts: The True Story of ‘The Bondwoman’s Narrative,’ set for publication in 2016. The book will tell Bond’s real-life story and the stories of additional characters he has come to know during the past decade, including other slaves he considered as possible Hannahs.

“The one thing I’m still searching for, to make a slam-dunk case, is something with Hannah Bond’s writing,” which, Hecimovich says, he could compare to the manuscript. He likens this to finding a fingerprint or DNA sample. “I’ve been able to discount other candidates this way.”

Bond may not have left such a fingerprint, but she had the courage to place clues to her identity in her novel, including real names, places and events. Her courage made it possible for Hecimovich to find her 150 years later.

Read a New York Times story about Hecimovich’s discovery.