Deliverance Helped Make James Dickey, BA’49, MA’50, a Household Name. Forty Years Later It Casts a Long Shadow over Southern Appalachia.

By Bronwen Dickey

Thick strokes of early evening crimson smeared across the rolling mountains of Rabun County as I drove up Highway 23 from Atlanta toward Clayton. The whole world looked like it was burning up right behind the horizon line. It was the 9-degree, molar-rattling middle of January in North Georgia, and I was on my way to visit the Chattooga River, 57 miles of fierce backcountry water and etched stone where the film of my father’s first novel, Deliverance, was shot in the summer of 1971.

When I read some months earlier that a lawsuit brought by a boating organization called American Whitewater had prompted the U.S. Forest Service to consider opening the river’s headwaters to boaters, an unexpected sadness came over me. The Chattooga River is generally recognized to be the wildest, most unforgiving in Southern Appalachia; its headwaters flow through some of the toughest terrain in the region. It’s a 21-mile stretch of swirling water where the battalions of rafters, kayakers and canoeists who float the rest of the river every year can’t go, or at least not legally. According to American Whitewater, it’s the only piece of river in the entire National Forest System, in fact, where boaters aren’t allowed.

The outside world has been pressing in for more than a century—the devastating logging period after the Civil War, the TVA dams following the Great Depression, the ever-increasing numbers of vacation homes going up—but it started pressing a lot harder when Deliverance hit theaters in 1972, and with that fact comes, for me, a twinge of guilt.

I wasn’t born until 10 years after Deliverance was filmed. What I knew of the river—and by extension, what I knew of Southern Appalachia—I knew only from the film and from memories of my father: the stories he told me and the bluegrass ballads he picked out on his guitar every morning before he worked on his writing. Both of my parents’ families had at one point come down from the hills, from North Georgia on my father’s side and East Tennessee on my mother’s.

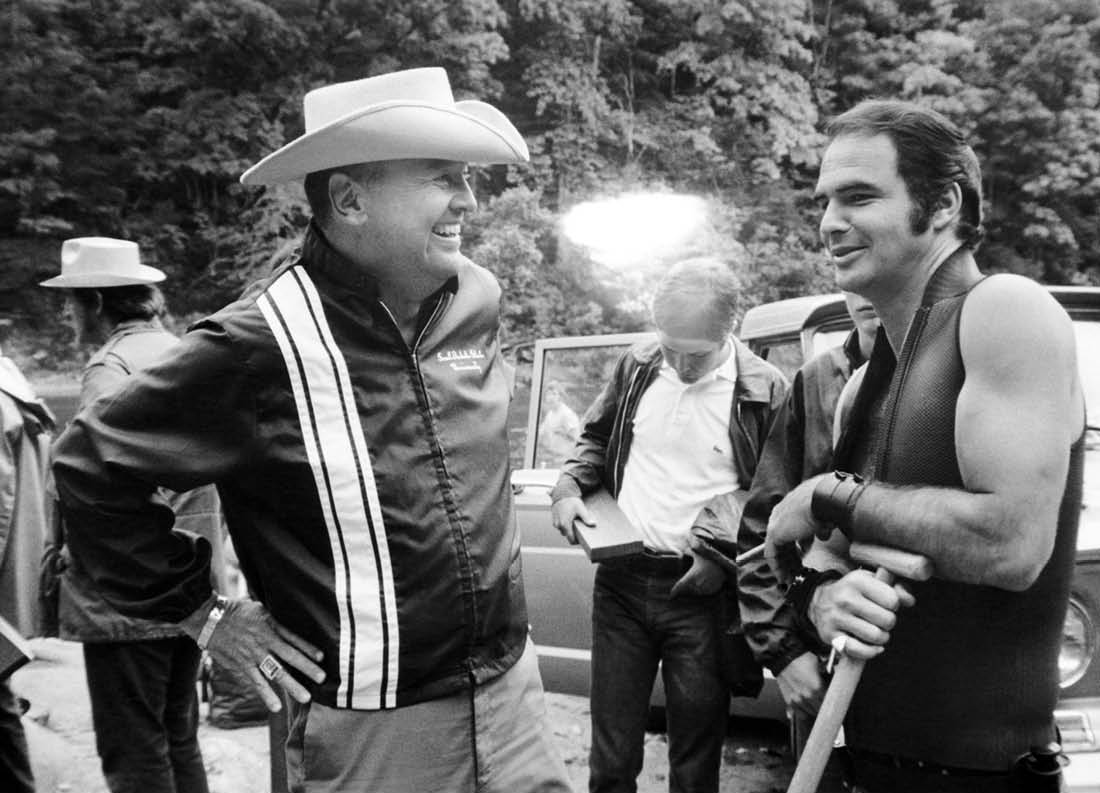

Ever since I was old enough to watch Deliverance, the river—called the Cahulawassee in the story—thundered through my imagination and, perhaps more important, pooled in a certain corner of my heart. It was where my father’s work came alive for millions of people and lodged itself permanently in the American brain, for better and for worse. Every time I watch the film and see the Aintry sheriff, played by my father at a healthy 48 years old, standing on the banks of the river, I want to reach right through the screen. And when I hear some version of the old spiritual “Shall We Gather at the River,” I remember him playing it on his 12-string, and I imagine the river in the song is the Chattooga.

I wanted to see the river while it remained, as it was called in the movie, “the last wild … river in the South.” I wanted the place that lived for me only in film and photographs and secondhand stories to live for me in a real way, in the winter, after the tourists had gone.

The river begins near Cashiers, N.C., then stretches along to form a good bit of the Georgia–South Carolina border before it turns back into Georgia, joins with the Tallulah River, and surrenders to Lake Tugaloo about seven miles south of Clayton. Its boiling rapids say as much about the people who named them as they do about the treacherous topography of the river itself: Warwoman, Bull Sluice, Sock ’Em Dog, Rock Jumble, Raven Chute, Jawbone, Dead Man’s Pool.

“It is,” as Buzz Williams, one of the principal founders of the Chattooga Conservancy, kept reminding me when he took me up into the headwaters, “a killer river.” He meant that 39 people have drowned in it since the Forest Service started keeping records on river fatalities in the ’70s. Several rapids are considered “certain death” if you are unlucky enough to fall into them.

Before Deliverance was released, only a few hundred people traveled down the river every year; after, that number jumped into the thousands and then the tens of thousands, and when a drowning occurred, it was attributed to “Deliverance fever.” Despite the river’s dangers—or maybe because of them—the lower Chattooga quickly became one of the most popular whitewater destinations in the country; in the past two decades, more than a million people have floated it. The fever may be gone, but there’s no question that the mystique of the Deliverance river endures.

Many of the locals were none too pleased with the flood of outsiders who arrived during the making of the film and for years after its release, especially when they began to see that the rest of America viewed them as violent, inbred rednecks. The sadistic mountain men in Deliverance were, of course, fictional, as were the town of Aintry and the Cahulawassee River, but the residents of Rabun County were left to contend with the peculiar legacy of the film long after the cameras stopped rolling. The theme from the movie, “Dueling Banjos,” is used in commercials to sell everything from dish detergent to SUVs. PADDLE FASTER—I HEAR BANJO MUSIC is printed on T-shirts and bumper stickers all over the South.

Most of the paddlers who flocked to the river were from elsewhere, and they soon became the lightning rod for local resentment. People told me stories of boaters who left their cars in parking areas near river put-ins and came back to smashed windows and slashed tires. Even as late as the mid-’80s, they said, arson was a problem. So was theft. Backwoods roughnecks trying to scare off paddlers sometimes fired warning shots from the bank, strung barbed wire across the river to slash up rafts, or even hauled boats right out of the water.

Buzz drove me up to where the headwaters ended and the rest of the river began. I was in the South, certainly, but it was not the suburban South I grew up in or even a South I recognized. It was a place where people accepted the dictates of the land they were living on and understood its character, a place free—at least for now—of the gated communities and department stores, happy hours and hustle that make so many cities interchangeable.

On the way back to Clayton, we passed an old sign, so faded that I struggled to read it: AMUSEMENTS, PICNICS, COLD BEER, USED CARS. Buzz told me it was the sign for Burrell’s Place, a small bar where everyone used to sit out on the front porch and drink beer while a guy named Junior Crowe played the banjo. Before it closed years ago, all kinds of people gathered at Burrell’s: rich kids from Highlands, hippie river guides, old-timers and farmers from the mountains. It was the sort of place that doesn’t exist in Chattooga country anymore.

Driving through the backcountry reminded me of the first scene in the novel Deliverance, where the four main characters, Atlanta suburbanites, are sitting in a bar planning a canoe trip in the mountains. Lewis, the hard-edged survivalist of the group who lacks the pure instinct for actual survival, points to the Cahulawassee on his map, set to be dammed up and turned into a lake for hydroelectric power (as so many rivers were back then), and explains to the others, “Right now it’s wild. And I mean wild. It looks like something up in Alaska. We really ought to go up there before the real estate people get hold of it and make it over into one of their heavens.” Famously, this is a trip that throws the men into a horrifying struggle for their lives: One is raped, another shatters his leg, another is killed on the river.

My father didn’t talk much about wilderness; it was “wildness” he was interested in. Wilderness, to him, was just an idea, a romantic falsification of nature rather than the untamed, untamable thing itself. Wildness was a place where man risked everything; it wasn’t a theme park or a toy you played around with or a place you ventured into for thrills. It could kill you. The characters in Deliverance were prepared only for wilderness, and they found wildness. Wildness bites back.

“I think a river is the most beautiful thing in nature,” my father wrote in one of his journals, right before the novel was published in 1970. “Any river is more beautiful than anything else I know.” He was drawn to writers who felt similarly inspired by water, like Melville and Conrad. Heraclitus’ philosophy of universal flux and his famous dictum, “you cannot step into the same river twice,” particularly moved him. But few things terrified my father as much as man’s ever-growing intrusion into the natural world. “We’re never going to be able to get out of the ‘man world,’” he said in a documentary back in the ’70s, “if we don’t have any place to go to from the man world. That’s why we need these rivers and streams and creeks and woods and mountains. You need to be in contact with nature, as it was made by something else than men.” As much as Deliverance is a story of survival or, as so many define it, a story of “man against nature,” it is a story about the commercial destruction of a rugged, primordial landscape and a part of the South that was slipping away, even back then.

Right across the river from Clayton, the Long Creek Bar is a plain, white box of a building that looks like it might have been converted from something else, like a warehouse for three-wheelers. On the night I stopped in with Buzz to grab a beer, leftover Christmas garland sagged off tables in the back, waves of cigarette smoke stung my eyes, and two guys in trucker caps shot pool while AC/DC’s “Shoot to Thrill” played feebly on the jukebox.

Buzz ordered a Budweiser and sat down at the bar next to a 60-something-year-old man with a bushy beard and camo cap whom he knew from the old days at Burrell’s Place. The man had clearly had a few, and when the subject turned to the fight over the upper Chattooga, he took a long drag from his Winston and became agitated, like he couldn’t stand to hear another word about it. “All I wanna know is,” he said, “if they open up that upper river, who’s gonna pay to get the bodies out?”

Buzz asked him what some of the old-timers from Burrell’s might have thought about all the controversy, and the guy shook his head and rested his hands on his pack of cigarettes. “I don’t know about that, but I do know that the worst thing that ever happened to this area was that …”—I knew what was coming—“that Deliverance.”

I was silently grateful that he didn’t know who I was. Half of me wanted to apologize to him for something, and half of me didn’t feel there was anything to apologize for. That was a feeling I walked around with my entire time in Chattooga country: a shadow of guilt about the lasting legacy of Deliverance doing battle with the pride of my father’s work.

On my last day in North Georgia, I drove over to Mountain Rest, S.C., to meet up with Butch Clay, who wrote a guidebook about the river and possesses an intimate knowledge of the headwaters area. He and I drove to a small parking area near the Chattooga River Trailhead, packed up two sets of hip waders and some lunch, and started our hike to the gorge, some of the most intractable wilderness on the entire river.

The gorge looked like a hulking rock coliseum, with the pine-covered mountains forming a steep V on either side that the noonday sun blanketed with light. The wind galloped through with as much purpose as the river did, chilling my skin under all the layers of sweat-soaked clothes. Once we picked our way down the river, we saw that there were thin sheets of ice all over it, looking like someone had encased the scene in glass. “Rime ice,” Butch said, as he broke off some of it with his boot. Every so often a huge sheet of ice would break off a ledge somewhere in the gorge and crash into the water, and I would wheel around, thinking it was a bear or a wild hog.

Eventually, we climbed onto an imposing boulder and talked while we ate lunch about the people who wanted to bring boats to the upper river. The tide of tourism seemed inevitable: The three major cities nearby—Atlanta, Asheville, Chattanooga—are growing all the time, as are the popularity of whitewater sports and the technology with which those sports can be enjoyed.

The last time my father saw the river was in 1988, when he visited it on a snowy winter weekend to participate in a short film about his career. Buzz Williams showed him around, and some months later, after the documentary aired in Columbia, S.C., Buzz told me that my father shook his hand at the screening and said, “Say goodbye to the river for me.” In a dark twist on that line from Heraclitus, he knew that he could never step into the same river twice, and the Chattooga that existed as a site for Deliverance tourism wasn’t the same river he stepped into back in 1971.

Sitting in the Rock Gorge, I looked around at the ice-sheathed cliffs and fallen trees spanning the water and wanted everything I could see to stay right like it was, as my father had once seen it. In my heart, if not my head, I wanted the glittering, jade eyes of the last cougar in the South to study me from under a ledge. I wanted to feel that cold fear that sluices through your veins when you realize you’re truly alone out in the wild—or that you aren’t. Emerging from the woods at dark-thirty (the Appalachian term for half past sunset), looking rougher, as my dad used to say, than a night in jail, I wanted to drive back down out of the mountains knowing that the people who had been living there for generations weren’t in any danger of being forced out, because I didn’t want to walk around in 50 years and see flattened patches of grass where the farmers and moonshiners and hell-raisers used to live. And, before I arrived home, I wanted to stop at Burrell’s Place and drink a beer out on the porch while Junior Crowe played songs that sounded familiar to me. “Shall We Gather at the River,” maybe. That’s one I know.

Bronwen Dickey, the youngest child of the late poet and novelist James Dickey, is a graduate of Duke University, where she studied American history and English literature, and Columbia University, where she received two fellowships in creative writing and taught literary nonfiction. She is a regular contributor to The Oxford American, and her work also has appeared in Newsweek, Outside, and The San Francisco Chronicle, among other publications. This essay is abridged with permission from a longer piece first published in The Oxford American and later included in The Best American Travel Writing 2009.