America’s Drug War Has Led to a ‘New and Improved’ Racial Caste System, Argues Michelle Alexander

By Arnie Cooper

Michelle Alexander didn’t set out to do her undergraduate work at Vanderbilt. As a high school senior living in Ashland, Ore., she planned to attend the University of Oregon like many of her college-bound classmates. Then one evening as she worked on her college application, Joanna Evins Carnahan, BA’61—an old friend of her mother—called.

“She asked about my grades, and my mother told her I had been doing quite well,” remembers Alexander. “‘Oh, Michelle should apply to Vanderbilt; that’s where I went,’ the woman said. So I applied to Vanderbilt and wound up getting a huge academic scholarship.”

The offer of admission, complete with a Gertrude Vanderbilt Minority Scholarship, couldn’t have come at a better time. Alexander’s family was struggling financially, and she couldn’t even afford to visit the university. But her parents viewed the opportunity “as the chance of a lifetime,” and she was soon on a plane bound for Nashville and life as a Vanderbilt freshman.

Alexander majored in political science, and although she was unsure exactly how her life’s path would unfold, her time at Vanderbilt helped put her on a track dedicated to fighting for social justice.

“The truth is this: We have allowed a human-rights nightmare to occur on our watch,” she told a packed house at Langford Auditorium back in January while delivering the keynote address for Vanderbilt’s annual Martin Luther King Jr. Commemoration. “In the years since Dr. King’s death, a vast new system of racial and social control has emerged from the ashes of slavery and Jim Crow.”

Alexander, BA’89, was referring to the issue she has been fighting tirelessly against: mass incarceration. To be sure, the statistics are alarming. The American prison population has exploded from 300,000 in the mid-1970s to more than 2 million people today. What’s worse, she told the audience, “more African American adults are under correctional control today in prison or jail, on probation or parole, than were enslaved in 1850, a decade before the Civil War began.”

Alexander attributes these grim facts to a “get-tough” mentality linked to a war on drugs that has been directed almost entirely against people of color. The result is “a far more extreme form of physical and residential segregation than Jim Crow segregation,” she argued in a Time magazine article last year. “Bars and walls keep hundreds of thousands away from mainstream society—a form of apartheid unlike the world has ever seen.”

In 2010, Alexander published her first book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (The New Press). The book, which philosopher and activist Cornel West has called “a grand wake-up call in the midst of a long slumber of indifference to the poor and vulnerable,” appeared on The New York Times bestseller list for more than a year.

In 2010, Alexander published her first book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (The New Press). The book, which philosopher and activist Cornel West has called “a grand wake-up call in the midst of a long slumber of indifference to the poor and vulnerable,” appeared on The New York Times bestseller list for more than a year.

Alexander has traveled the country consulting and advising advocacy organizations waging campaigns in an effort to mobilize people to end mass incarceration. She’s also written about the topic in op-ed pieces for The New York Times and in articles for The Nation and Time. And she has spoken at more than 100 events at venues ranging from universities and legal conferences to prisons and churches.

Despite her sweet voice and sunny disposition, Alexander exhibits a passion for helping the oppressed that sets her apart from other civil rights advocates—a defining characteristic that took root during her four years at Vanderbilt.

During her junior year Alexander participated in Alternative Spring Break in Lexington, Miss., working voter registration in an all-black community surrounding the city known as “Balance Due.” So named because the area’s white residents had drawn a line around Lexington that excluded the black segments of town, Balance Due was still recovering in the 1980s, Alexander says, from a history of voter disenfranchisement.

“Black people would be told their names weren’t on the rolls, or that some technicality prevented them from registering,” Alexander remembers. “Residents were often too confused or intimidated to challenge these tactics.”

Beyond getting a direct look at voter suppression, Alexander was immersed in a world of crumbling buildings and extreme hardship that energized her to battle for social change. The next year she got her first taste of the prison system while working as a volunteer visitor at the Spencer Youth Correctional Center in Nashville.

Through a series of visits with a young girl, Alexander became haunted by the notion that she herself could have ended up behind bars. The venture clearly left its mark, and Alexander has spent much of the past decade as an advocate for individuals who were locked up as targets of the drug war.

“I’ve really been devoted to challenging how the system of mass incarceration has decimated communities,” she says. “It’s almost felt like my calling in life.”

Early Lessons

Born in Chicago in 1967, Alexander spent part of her childhood in Stelle, Ill., a 300-person intentional community known as one of the country’s first models of sustainable living. As the offspring of an interracial couple (her mother is white; her now-deceased father was black), she learned firsthand the challenges of racial integration. Although her parents were married the year after the Civil Rights Act of 1964, her mother was disowned by her family and excommunicated from her church.

Her father faced other difficulties, notably in his work life. After IBM transferred him to the San Francisco Bay Area in 1975, he became one of his office’s top salespeople. Unfortunately, climbing the corporate ladder proved impossible for him, and he eventually left his job. As a result, the family began moving from place to place. Despite having to grapple with being evicted from her home and attending three different high schools, Alexander says a bright side emerged from those chaotic years.

“I was exposed to many different types of communities growing up, so I became friends with, and came to love, people from vastly different backgrounds. I’ve had close friends of every race and ethnicity—rich, poor and everything in between.”

After Vanderbilt, Alexander attended Stanford University Law School, where she was greatly inspired by Gerald López, who co-founded a program called Lawyering for Social Change.

“I think I had a little bit of a fairytale idea of civil-rights lawyers riding in on their white horses to save a community,” says Alexander. “He disabused me of those notions and challenged my thinking in very important ways that have influenced how I’ve thought about my work as a lawyer and advocate ever since.”

While at Stanford, Alexander served as director of the Civil Rights Clinic. After graduating in 1992 she worked as an associate at Saperstein, Goldstein, Demchak & Baller, fighting race and gender discrimination in Fortune 500 companies. Then, in 1998, she switched gears to focus on criminal justice reform at the American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California.

In her book Alexander tells the story of her first encounter with the notion of a “new and improved” racial caste system that happened some 15 years ago. “I was rushing to catch the bus, and I noticed a sign stapled to a telephone pole that screamed in large bold print: THE DRUG WAR IS THE NEW JIM CROW.” Ironically, that was the day she began her new job as director of the Racial Justice Project at the ACLU.

Inequality’s Primary Engine

Thus began Alexander’s “process of awakening” to the harsh reality that the criminal justice system isn’t just “infected with racial bias” but “functions as the primary engine of racial inequality and stratification in the United States today,” she says. “My own view is that no one should be put in a cage and branded a felon for the rest of his life because of drug abuse or drug addiction, or because they were once caught with drugs,” says Alexander.

Rather, she believes drug abuse, like alcoholism, should be treated as a health problem, not as a crime. Still, Alexander didn’t always see things from this perspective.

“There was a time,” she continued in her keynote address at Vanderbilt, “when I rejected mass comparisons between mass incarceration and slavery, mass incarceration and Jim Crow, believing that those kinds of claims and comparisons were exaggerations and distortions—even hyperbole.”

Like many in this country, Alexander had believed that people of color were more likely to sell drugs than whites or that incarceration rates could be explained by the level of crime. “I believed a lot of the myths that most Americans believed, and only after years of working on these issues did my eyes open,” she says.

One of her current endeavors, working in association with the Calhoun School, a college preparatory school in New York City, is the Deconstructing Race Project, a novel curriculum designed to expose the “myth of colorblindness”: the idea that society must ignore race in order to transcend racism. For Alexander the main failure of such a mindset is that it’s simply not feasible to remedy centuries of racial discrimination without taking race into account.

The project will provide teachers with various resources, including webinars and videos designed to encourage students to engage in an honest dialogue about their experiences and perceptions concerning racial issues.

Currently a law professor at Ohio State University, Alexander teaches courses on race, civil rights and criminal justice. She is married to Carter Stewart, who serves as U.S. attorney for the Southern District of Ohio. The couple has three elementary school-aged children.

Alexander is also working with two sets of filmmakers to create a full-length documentary about her book as well as a series of short films, which can be shared through social media, on topics like undocumented immigrants and the expansion of private prisons.

Given the countless hours she has dedicated to exposing what she views as the immorality of mass incarceration, those who have followed her work may be surprised to learn about a quasi-confession she recently made in The Nation magazine. In her September article, “Breaking My Silence,” Alexander asserts that her singular focus on this issue has been too confining.

Like Martin Luther King Jr., who followed up his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech by speaking out against U.S. imperialism and the inequities of our economic system, Alexander too is compelled to confront other concerns facing the country—from the innocent people killed in the drone war to the bailout of Wall Street bankers.

“It’s not just about race; it’s also about an unwillingness to really care for people of all colors, all backgrounds, all walks of life and all economic levels,” she wrote. “The ultimate solution, I think, is to extend generosity to ‘others’ and to acknowledge the basic dignity and common humanity of us all.”

California-based freelance writer Arnie Cooper is a frequent contributor to The Wall Street Journal and The Sun Magazine. Cooper’s writing also has appeared in Poets & Writers, The Atlantic, the Los Angeles Times and Village Voice.

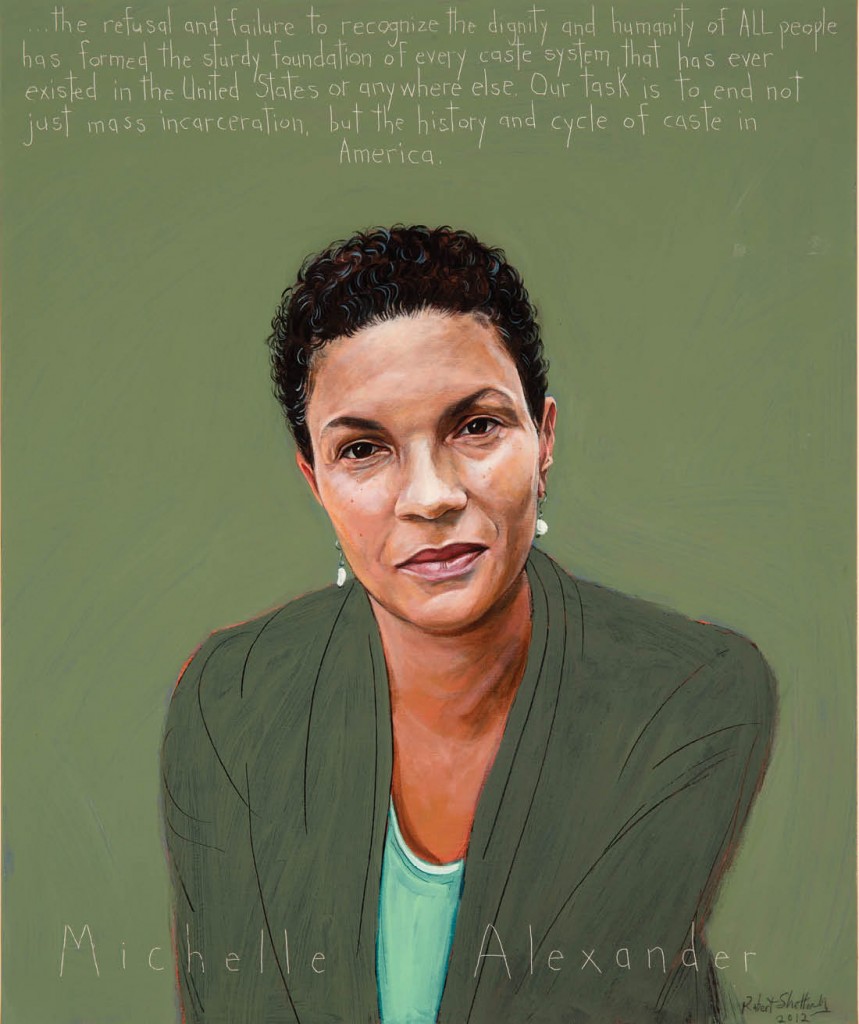

Painter Robert Shetterly has created nearly 200 portraits of American citizens who “courageously engage issues of social, environmental and economic fairness”—including the one above of Michelle Alexander—for his Americans Who Tell the Truth project.