By Brier Dudley

Illustration above by Otto Steininger

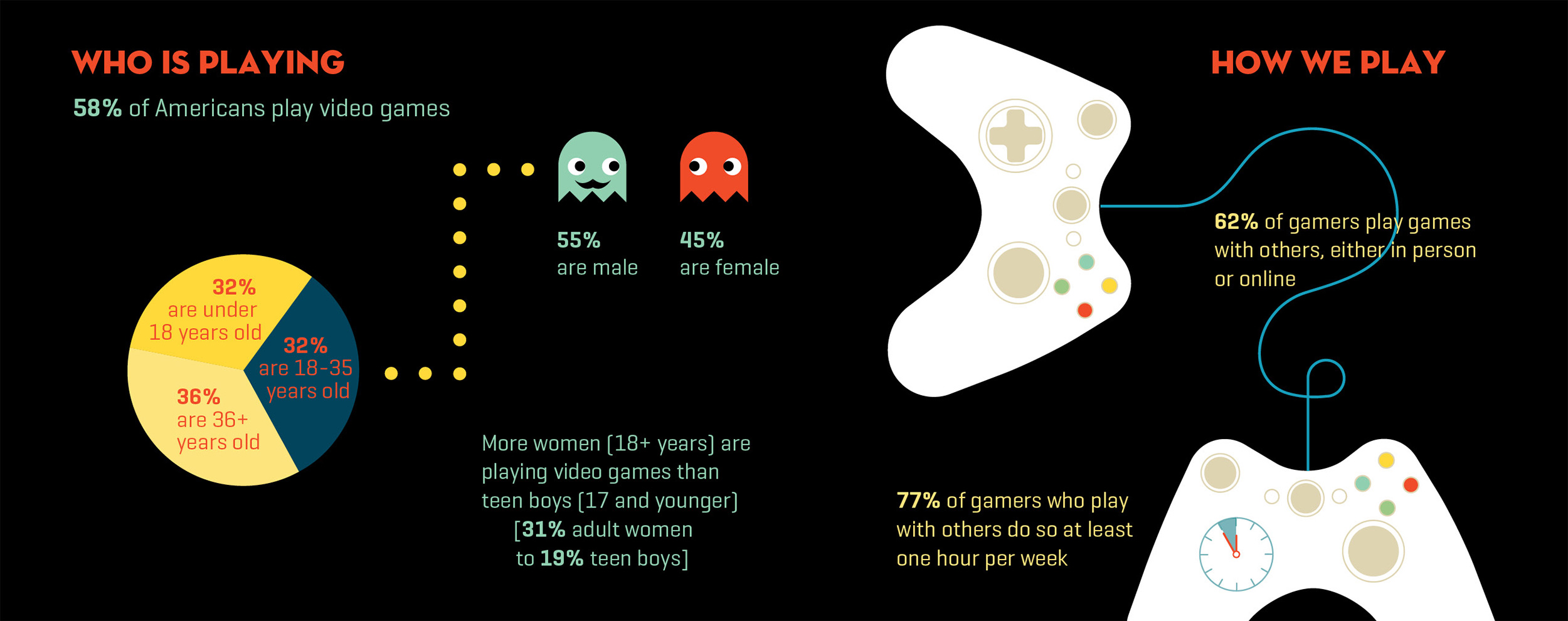

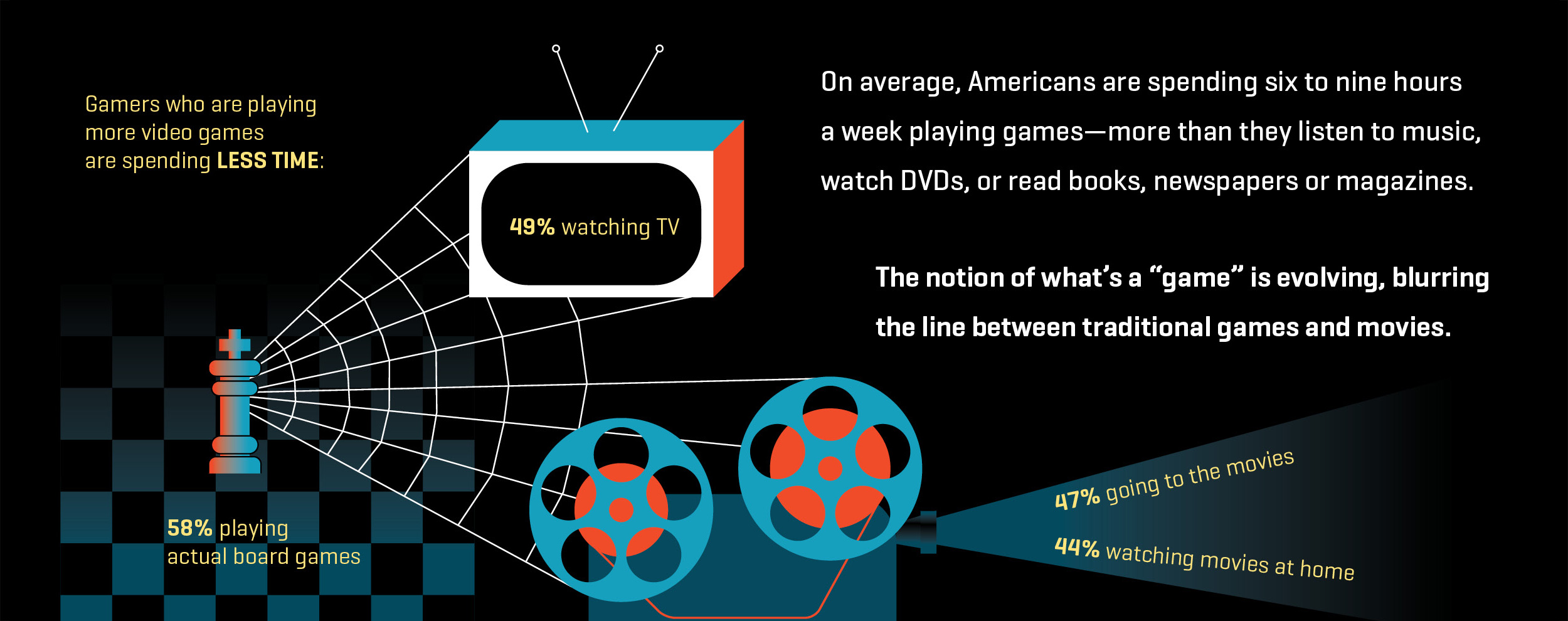

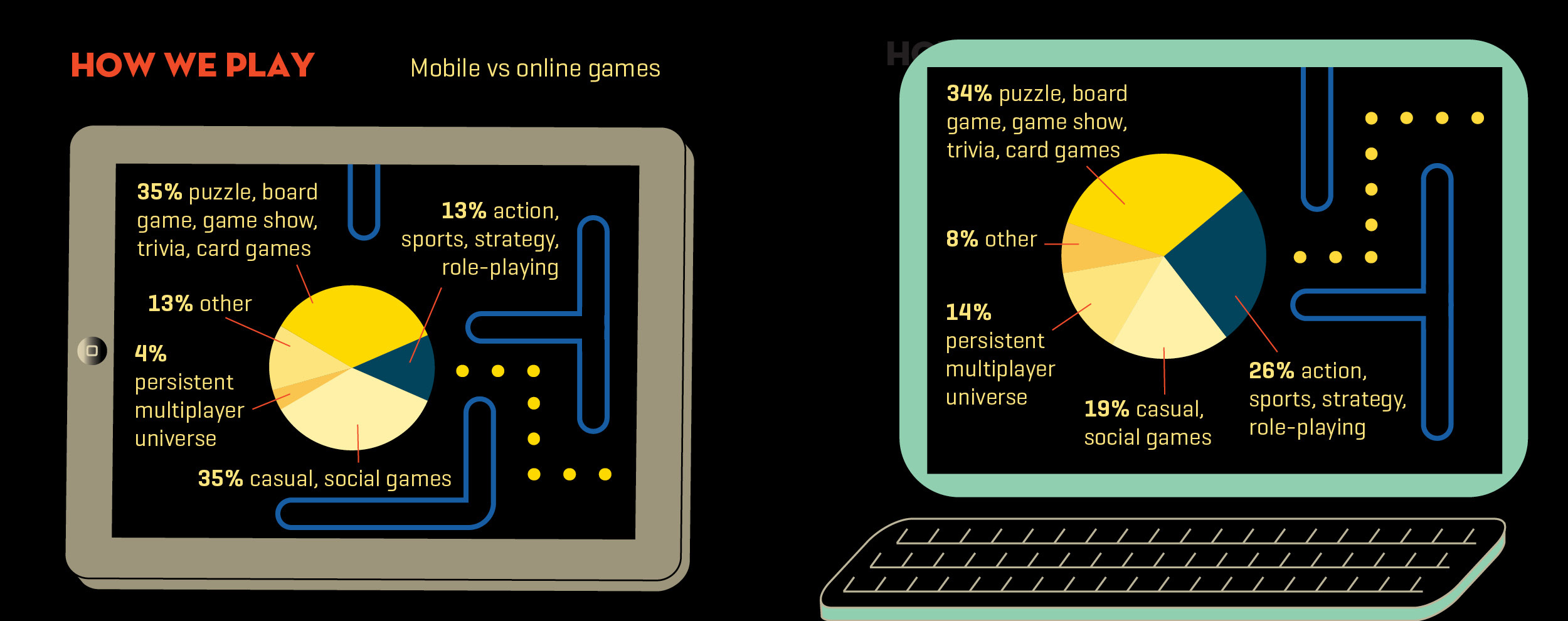

Forty years after Atari’s digital table tennis game Pong bleeped onto the scene and made video games mainstream entertainment, we’ve become a nation of video gamers. We’re playing games on phones, tablets, computers, game consoles, social networks, and even TVs connected directly to the Internet. | On average, Americans are spending six to nine hours a week playing games—more than they listen to music, watch DVDs or read books, newspapers or magazines, according to Nielsen research. And this isn’t just adolescent boys. The Entertainment Software Association reports the average age of video game players is now 30, and more adult women are playing games than teen males.

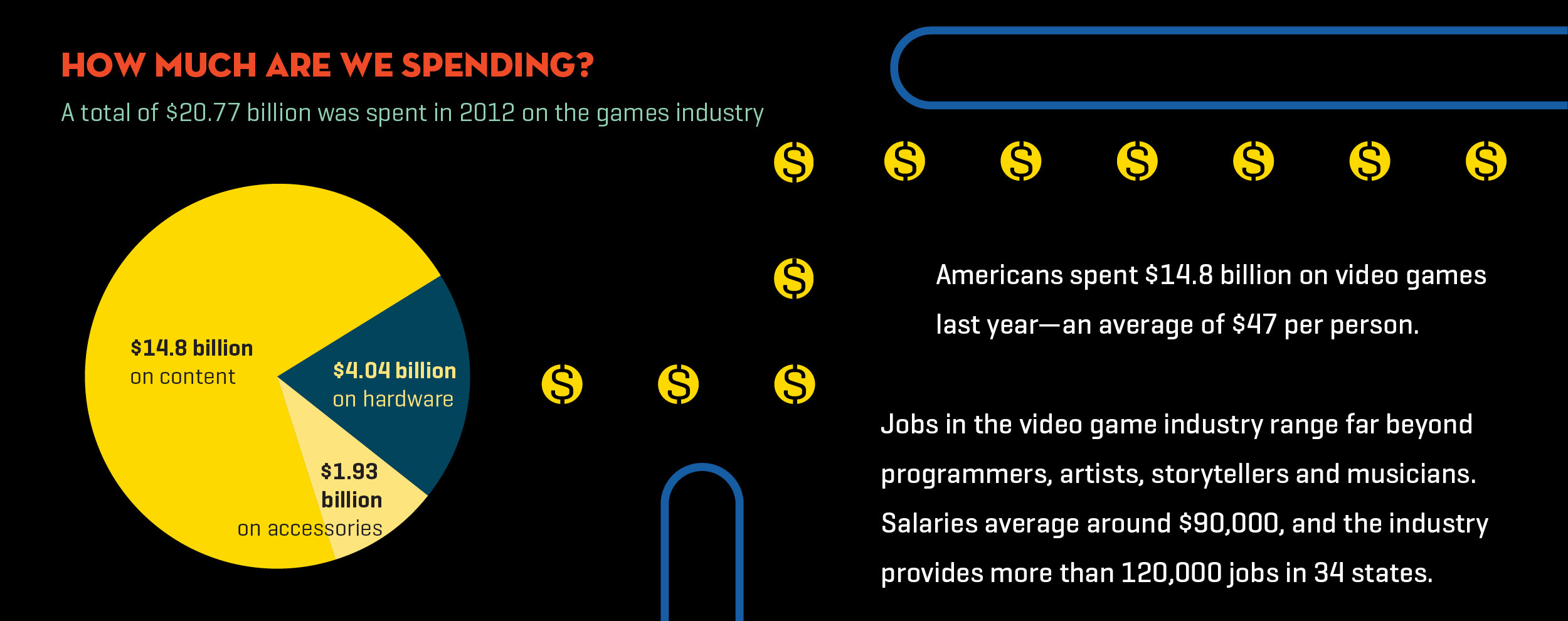

Altogether Americans spent $14.8 billion on video games last year—an average of $47 per person, according to research by NPD Group. (By comparison, movies grossed $11 billion domestically last year.)

Their popularity is no wonder if you’ve seen the latest games. Advances in computing and graphics technologies are enabling game designers to produce ultra-realistic titles that immerse players in movie-like experiences, letting them battle fierce aliens whose armor glints in the light of foreign moons, crawl through swaying grass to ambush sweaty mercenaries in a tropical jungle, or work out with a chatty personal trainer generated by software.

The notion of what’s a “game” is also evolving, blurring the line between traditional games and movies. Microsoft’s latest version of the blockbuster action game Halo was released alongside a series of live-action TV shows that expanded on the game’s science-fiction storyline. In May, Steven Spielberg signed on to produce the series’ next installment.

[quoteit]Gaming now has more economic impact than the film industry.[/quoteit]

Game publishers play up this success by comparing the sales of their biggest hits to the box-office take of Hollywood blockbusters.

Last year Santa Monica, Calif.-based Activision Blizzard’s military-themed action game Call of Duty Black Ops 2 made $500 million during its first 24 hours on the market and $1 billion during its first 15 days, reaching the billion-dollar milestone faster than the movie Avatar. Overall sales of Call of Duty games have now exceeded the box-office take of the Harry Potter and Star Wars movie franchises.

Football, Farms and Fantasy

The hybridization of entertainment genres is creating opportunities for new companies such as OverDog, a Nashville startup that connects gamers with professional athletes so they can play online sports and action video games together.

OverDog was co-founded in 2012 by two Vanderbilt alumni: Steve Berneman, JD’10, MBA’10, who serves as CEO, and Hunter Hillenmeyer, BS’03, who serves as president. A third alumnus, Thomas Bernstein, MBA’10, is vice president of product. Hillenmeyer, who was a Chicago Bears linebacker for eight seasons after leaving Vanderbilt, is drawing on his pro sports connections to build OverDog’s roster of players.

“Part of the coolness of OverDog is that we are sort of democratizing the relationships between athletes and fans,” says Hillenmeyer. “Waiting in an autograph line or hoping to catch a glimpse of a player at your favorite sporting event is different than having 20 or 30 minutes where it’s just you competing with [a pro athlete].”

OverDog is initially offering the connections for free, randomly choosing fans for gaming sessions. The company establishes a temporary connection between fans and athletes on game services such as Microsoft’s Xbox Live, where they compete in sports games such as Madden NFL and FIFA Soccer, as well as action titles like Halo and Call of Duty.

Although the game industry is concentrated in tech hubs such as Silicon Valley, Seattle and Austin, Hillenmeyer says OverDog is off to a great start in Nashville, where there’s a growing pool of engineering talent generated largely by the health care and music industries.

“It’s not Austin, it’s not the Valley or anywhere along the West Coast, but Nashville—well, don’t sleep on Nashville,” he says.

Other Vanderbilt grads have gone on to major gaming companies from Activision to Zynga, working on some of the biggest games in the industry.

They include Scott Tannen, BS’99, co-founder and former president of online game publisher Funtank, which was acquired by Publishers Clearing House in 2010, and Charles White III, BA’03, senior UI/UX game designer for San Francisco-based Zynga, producer of megahits FarmVille and CityVille. Zynga has more than 265 million monthly active users.

Josh Goldberg, BA’98, MBA’02, played games most of his life, starting with Pong and working up to early Atari and Nintendo systems before enrolling at Vanderbilt. But he never thought it would be a career, even after earning his MBA.

“I actually did a bunch of networking with alumni to figure out where I’d be,” says Goldberg.

It was a tough market at the time, so he moved to Seattle—his wife’s hometown—without a job. He kept networking, which led him to a fellow Vanderbilt alumnus working for a Seattle ad agency whose clients included Microsoft’s Xbox business, giving Goldberg an entree.

“I figured I’d be doing Windows or something—learning the ropes of marketing that way,” he says. “I hadn’t even considered that gaming would be a career for someone coming out of grad school.”

Goldberg developed and managed marketing campaigns for hits such as Microsoft’s Fable fantasy franchise and the record-breaking 2007 launch of Halo 3, which started the practice of comparing game launches to those of movies, books and music. After Microsoft, Goldberg eventually became director of marketing for gaming giant EA Sports, working alongside teams building titles such as Madden NFL, Tiger Woods PGA Tour and NCAA Football. EA Sports posted net revenue of $4.1 billion in 2012.

As gaming has become mainstream entertainment, it’s also become more recognized as a potential career, says Goldberg, who left EA Sports in June to be director of marketing for 2K Games in California. “Nowadays kids understand this and are saying, ‘I can be part of that.’”

[featurefullquote]Companies that are small, nimble, on tablets and mobile devices—those will be the hit makers of the future.[/featurefullquote]

The Business of Gaming

The video game industry offers a wide range of jobs, far beyond programmers, artists, storytellers and musicians. Salaries average around $90,000, and the industry provides more than 120,000 jobs in 34 states, according to the Entertainment Software Association.

Major titles involve teams of a hundred or more and budgets of $50 million or more. The bigger game companies are large organizations that need people for core corporate functions such as finance, accounting and marketing, explains Goldberg.

It’s particularly exciting from a marketing standpoint, he says, because game companies do “some of the coolest marketing out there,” reaching young consumers and staying on top of the latest technology and trends. That kind of experience develops skills that are transferrable to other technology firms such as Google and more traditional firms, such as those producing packaged goods.

“Gaming’s a legitimate work background now and not just a hobby area,” he says.

It’s also approaching an art form, a topic that’s raised in a course about online gaming and narrative theory taught by Jay Clayton, the William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of English at Vanderbilt. Clayton gets up around 5 a.m. to play Lord of the Rings Online, a free, massively multiplayer fantasy game that’s the core of his class.

Clayton chose that particular game because the class explores how narrative or storytelling changes as it crosses to different media, from Tolkien’s novels to movies to immersive games.

“Gaming is one of the largest industries for creative people in the United States—it now has more economic impact than the film industry, for example,” says Clayton. “It is intrinsically multimedia, bringing together stories—writers of narrative—with graphic design artists, with musicians, with highly skilled mathematicians and computer scientists.”

Because gaming is a multidisciplinary endeavor and engine in our economy, “I think it’s really important that universities explore this topic with their students and their research,” he says.

Clayton’s found a huge audience for the course beyond the usual 15-person seminars on campus. In July he started offering a free online version of the course—Online Games: Literature, New Media and Narrative—through Coursera, an online education company with which Vanderbilt partners, potentially drawing up to 40,000 students for the course. Students follow along online and must play the game as well.

Naturally, Vanderbilt’s computer science program also has its share of game enthusiasts.

“Some of our students are interested enough that they want to go on and do it as a profession,” says Douglas Schmidt, professor of computer science and associate chair of Vanderbilt’s computer science and engineering program. In fact, producing graduates for the entertainment industry, including video gaming, has been identified as one of four core strengths of the Vanderbilt School of Engineering by the school’s new dean, Philippe Fauchet.

What’s really blossoming lately is development of software for mobile devices, where games are generally the most lucrative apps sold to consumers. Schmidt says a lot of students are making money selling apps they’ve created, and 30 to 40 are part of a group called Vandy Mobile that’s been working on mobile projects and connecting with local businesses since 2008.

“It’s really an exciting time,” says Schmidt. “We can’t produce computer science graduates fast enough to meet the demand here, much less for the rest of the country.”

Other Vanderbilt alumni were indirectly inspired to enter the game industry, such as Jonathan Zweig, a 1989 graduate of Vanderbilt Law School who is now vice president for corporate alliances at Activision Blizzard, the world’s second-largest gaming company in terms of revenue. With sales of nearly $5 billion last year, Activision Blizzard publishes Call of Duty and World of Warcraft, the No. 1 subscription-based massively multiplayer online role-playing game in the world.

Zweig says so much creativity and development of intellectual property permeates Nashville—and, by extension, Vanderbilt—“that it certainly lets you know moving into the entertainment space is possible.”

Timing is also a factor. When Will Harbin, BS’99, chief executive of thriving San Francisco game company Kixeye, arrived at Vanderbilt in 1995, The Wall Street Journal seemed to have a story every day about a new tech company going public. “I considered dropping out and moving to Silicon Valley,” he admits. “In hindsight, though, I’m glad I finished and got my degree because of all the things I learned and was exposed to at Vanderbilt.”

A gamer since he was 5 years old, Harbin had built his own games in his teens. While studying engineering at Vanderbilt, he built modifications of the PC game Quake and built a tank game for a multimedia programming class.

But Harbin took a roundabout path to make games his career.

Between his junior and senior years at Vanderbilt, he started a software company called Media1st that was eventually sold. Later he worked for Netscape and Yahoo before co-founding Affinity Labs, a San Francisco company that builds social networks for groups such as police officers and firefighters.

After Affinity was sold to job-listings company Monster Worldwide for $61 million in 2008, one of its investors brought Harbin aboard to hatch another business. But he was lured away to overhaul a struggling online game company called Casual Collective, which he immediately turned profitable, according to a March profile in The Wall Street Journal.

Harbin renamed the company Kixeye and shifted from a strategy of selling ads around its games. Instead, the games are offered for free and players are encouraged to buy virtual goods, such as modifications to the futuristic warships they fight with in Kixeye’s Battle Pirates.

Still, the company was having trouble raising its profile and attracting job candidates until Harbin produced an outlandish, brassy YouTube video called “The Interview” that mocked some of its competitors in the gaming industry as greedy and out of touch.

The video became a viral hit, and Kixeye employment surged from 100 to 450, including 400 in the San Francisco area, 30 in Brisbane, Australia, and 20 in Victoria, B.C., Canada. New offices are opening soon in Portland, Ore., and Amsterdam. Sales are “nine figures” and expected to grow 200 percent this year, says Harbin. Kixeye games are played through PC browsers and tablets, but by the end of the year the company plans to have launched four new titles for mobile devices such as smartphones.

Digital Transitions

Harbin’s success is especially remarkable since it’s happening during a period of contraction in the U.S. game industry.

People are spending more time playing games, and overall sales of games are expected to continue growing around 7 percent a year, reaching $83 billion in 2016, according to PricewaterhouseCoopers. But during the past two years, the industry has gone through a painful transition period.

Sales of packaged games and game hardware such as the Xbox and PlayStation consoles have fallen for two years in a row as people turn to less expensive digital games played online and on mobile devices. That’s led to layoffs, studio closures and executive turnover at large game companies.

A decline is natural late in the life cycle of hardware. The current Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3 have been on sale nearly eight years and no longer have cutting-edge graphics; games played on some mobile devices are approaching the fidelity of the consoles.

New versions of the Xbox and PlayStation with dramatically improved horsepower are going on sale this holiday season, joining the Nintendo Wii U that went on sale last fall. All three “next generation” systems are designed to make game-controlling feel more natural, using physical gestures rather than just pressing buttons on a controller.

These new consoles were also designed from the start with broader entertainment in mind. All three have built-in services to stream music and movies and communicate with other players connected via their online networks.

Whether the new hardware reinvigorates the traditional video game business remains to be seen. Meanwhile, the transition is creating opportunities for newcomers such as Harbin, who has been hiring people let go by other game companies.

“We’ve definitely benefited from the misfortune of other companies,” he says. “People are still playing games; they’re just digesting entertaining game content from other places. They’re not just going to Best Buy and buying an Xbox and sitting in the living room and playing—consumers have a lot more choices.”

Opportunity is shifting and not necessarily going away. Goldberg notes that gaming is the top application on the fast-growing iOS and Android mobile platforms, creating “massive” advantages for companies that figure it out quickly.

“It’s absolutely an exciting industry—it’s fun, it’s young, it’s a blast to be part of,” says Goldberg. “At the same time it’s in transition, so there’s an opportunity. Companies that are small, nimble, on tablets and mobile devices—those will be the hit makers of the future.”

Back in Nashville last spring, Hillenmeyer’s OverDog spent late nights and weekends to finish the game in time for its debut on Apple’s iTunes Store. “The guys on the tech side of the building literally haven’t taken a day off in three weeks,” he said by phone during the crunch period.

In a way it was like being back at school. Even though he’s in a career he’d never imagined, in a vibrant new industry that’s changing notions of entertainment around the world, some things don’t change—he still doesn’t have enough time to play.

“It’s hard to find enough time to play video games—and that’s a sentence I never thought I’d get to say in a professional setting.”

Brier Dudley is a writer, columnist and blogger about technology and business issues for The Seattle Times. He has a weakness for console action titles like Halo, as well as anything from Clue to Super Mario Bros. that he can play with his daughters.