BY ROD WILLIAMSON

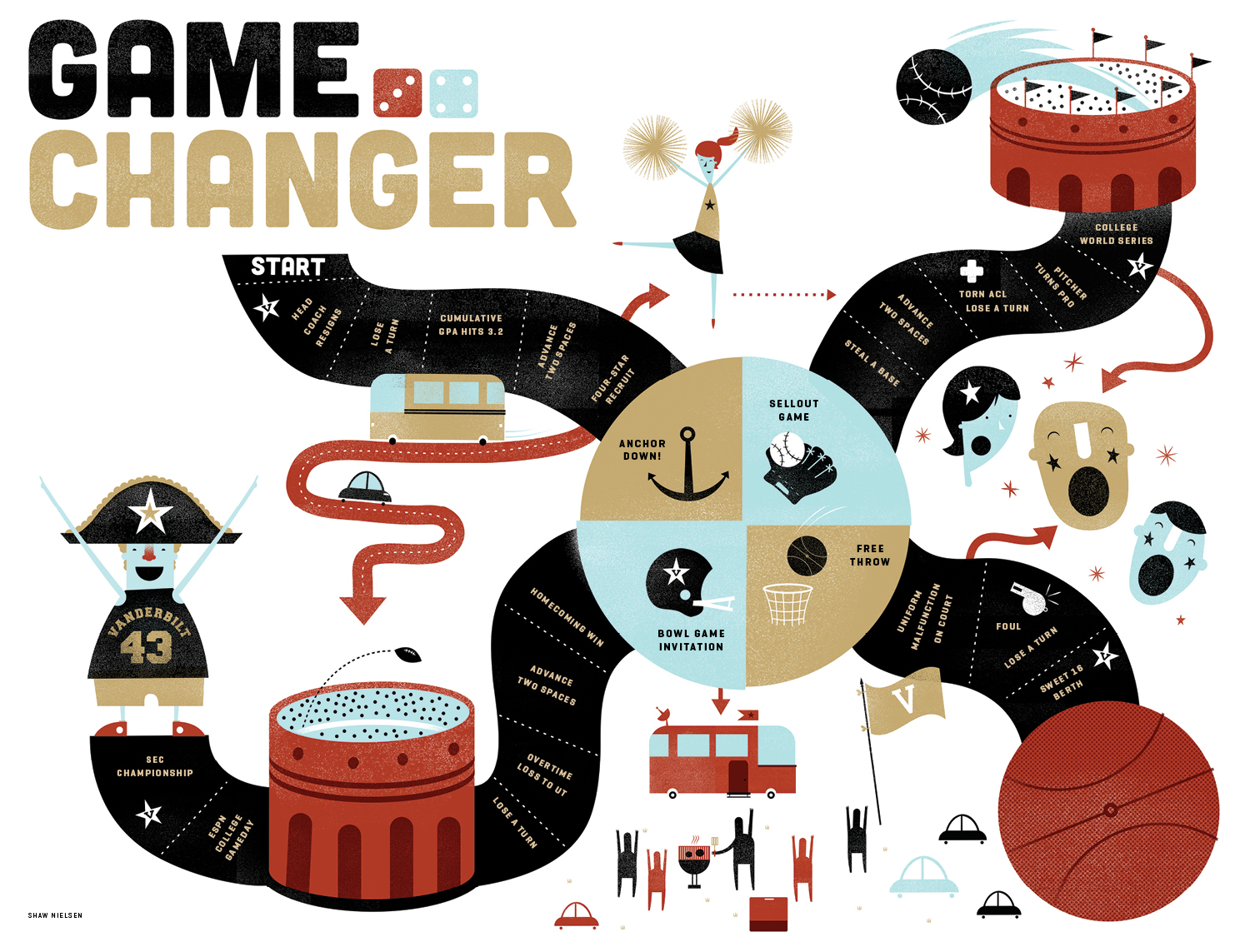

ILLUSTRATION BY SHAW NIELSEN

In December 2010, a relatively unknown Maryland assistant football coach named James Franklin arrived in Nashville to occupy a hot seat that had scorched a long list of more seasoned men—that of Vanderbilt University’s head football coach.

In the football-crazy South, a college athletic program can enjoy success in every sport but football and still be deemed a dud—or it can win in football, be mediocre at everything else, and sit at the adult’s table. Vanderbilt had a good overall athletic program, but football had enjoyed just five winning seasons since John F. Kennedy was president.

Before Franklin’s first season, beat-down fans listened as the new coach outlined his plans for success, smiled faintly and whispered, “God bless his enthusiasm—but he doesn’t know what he’s getting into.”

Franklin has brought much to Vanderbilt, but it was his “burn the boats” mentality in a dogged pursuit of excellence that was game-changing to many. A month into his first season, fans were amazed. Within a year, area merchants were selling more licensed Vanderbilt gear than any other sports entity in the state.

The year after Franklin’s arrival, just eight major college sports programs in the nation that sent their football teams to a bowl game also sent both their basketball teams and baseball teams to the NCAA Tournament. In 2012, six universities could make the claim. Only one university could claim this distinction both years: Vanderbilt.

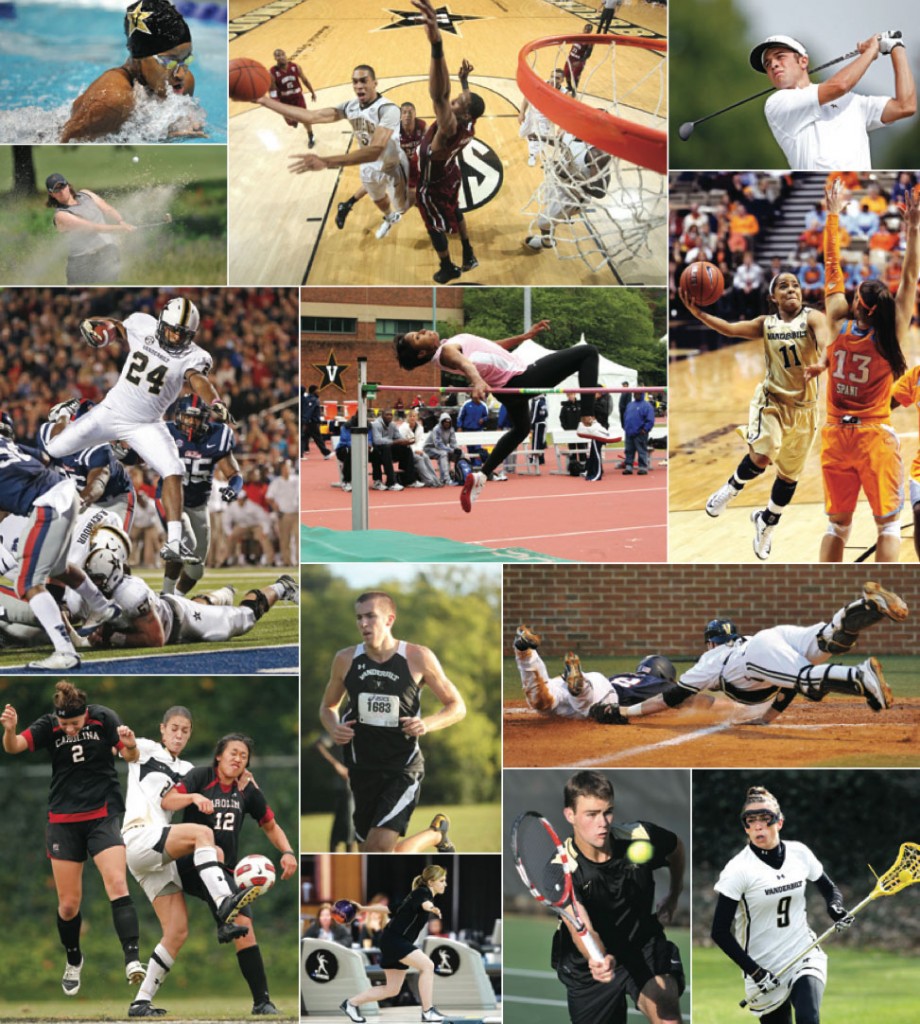

Vanderbilt’s recent triumphs also include a trip to the College World Series; Southeastern Conference basketball tournament championships for both women’s and men’s teams; top 20 rankings for women’s and men’s golf, women’s tennis and lacrosse; and the first-ever SEC title for women’s cross country.

And there is an ever-improving academic report card: For each of the past six years, student athletes have had increasingly better cumulative grade point averages—now nearing 3.10.

The “new Vanderbilt” has “anchored down,” in the current parlance of Commodore Nation.

Revolution and Rumors

Only the most die-hard fans would have dared to predict this level of success a decade ago when then-Vanderbilt Chancellor Gordon Gee shocked the sports world by announcing in September 2003 that Vanderbilt was disbanding its Department of Intercollegiate Athletics. His action was prompted by embarrassing athletic scandals around the country and concern that college athletic departments were becoming islands unto themselves.

Fans were aghast. College sports enthusiasts were confused or amused. Media had a field day. Vanderbilt would soon have its Kappa Sigs playing Florida, they crowed, and every coach worth his or her salt would be out the door by sundown.

In hindsight, the announcement was a bit over the top. Although family and friends called athletic staff members, concerned they were suddenly unemployed, the reality was the keys still worked to McGugin Center doors and the basic machinery remained in operation, under new management.

Gee turned to David Williams, a trusted deputy he had recruited from Ohio State who was serving as Vanderbilt’s vice chancellor for student affairs, general counsel, and secretary of the Board of Trust. Williams did not fit the prototypical SEC athletic director’s profile, although the Buckeye athletic director had reported to him at Ohio State.

Amid the chatter, few grasped the present, let alone the future. Williams’ commitment to excellence went unnoticed by most, who were content to mock the unique model. But he had two clear priorities.

“The first was to make sure people didn’t act on the basis of fear,” he recalls. “The way the announcement came about produced a lot of uncertainty: Were we doing away with athletics? I wanted people to realize this wasn’t something that would make us worse. I was focused internally, especially on the athletic staff, the student athletes, the boosters and our fans.

“On the other hand, I didn’t want the announcement to be seen as affirmation of what some people hoped might happen: ‘Ah, this is good, we are going to get rid of athletics.’”

Beyond reassurance and explanation, Williams developed a plan. Where did Vanderbilt want to go, and how would it get there? The trip would take some time.

Even today, surprisingly few pundits recognize the rare combination of credentials Williams brought to scale the hill. Sitting on the university’s Senior Management Council, he had the ear of top administration and the pulse of the campus. As secretary of the Board of Trust, he earned the confidence of trustees. And while keeping his faculty appointment to teach at Vanderbilt Law School, he had the respect of the faculty.

“I always thought being a member of the faculty allowed me to say things to them that others couldn’t because I was one of them,” Williams says. “I understand the faculty. I do believe Vanderbilt is a place where developing degrees of credibility really helps you get things accomplished.”

But credibility is earned, not given. Shortly after the announcement, trustees descended upon campus on a Saturday, frustrated and seeking answers. “We had some board members who were absolutely livid,” Williams remembers. “I spent the day with them, and they were mad. But at the end of that day, it was clear they cared. And I had gained a little more credibility. As bad as that Saturday was, it actually helped a lot.”

Williams says he never lost sleep during the tumultuous days, mostly because he could visualize the future, which always included SEC membership. He tried to dispel rumors he called “borderline ridiculous.”

For the record, no head coach would leave Vanderbilt for nearly four years. The exodus never occurred. To the contrary, most signed long-term contracts.

Head Baseball Coach Tim Corbin arrived with little fanfare a decade ago. Using a combination of university academic and athletic assets, extraordinary recruiting skills, and a fanatical work ethic, he not only built his Commodores into a perennial national powerhouse but perhaps showed other Vanderbilt coaches a model of how it can be done.

“I wasn’t ready to step into a head coaching position unless I felt it had a balance of strong academics and athletics,” Corbin recalls. “That was my background—working with kids who had more of a commitment to school than the average baseball player. I thought that was important in building a program. I wanted a young man who could see himself in school for four years and the ability to retain kids who could possibly be confronted by professional baseball. I knew those were keys to winning.”

FANS CELEBRATE THE VANDERBILT COMMODORES’ BEST SEASON SINCE 1915 IN THE DEFEAT OF NORTH CAROLINA STATE 38–24 IN THE FRANKLIN AMERICAN MORTGAGE MUSIC CITY BOWL ON NEW YEAR’S EVE 2012 (CREDIT: JOE HOWELL)

In the summer of 2007, Vanderbilt faced another period of uncertainty when Gordon Gee departed to return to Ohio State as president. Despite his unilateral action, Gee had been an ardent cheerleader by nature. Some wondered if the sports gods would be kind to the Commodores when the flamboyant chancellor left.

Worries of a decline were soon put to rest, however, when Nicholas S. Zeppos, the university’s provost, was promoted to interim chancellor and, finally, chancellor. Zeppos carried an academic’s portfolio with a sportsman’s competitive heart, quickly affirming his desire for athletics to maintain a meaningful place on the campus.

“I love sports,” says Zeppos. “When I came to Vanderbilt, part of the draw was being in the SEC. And we had successes along the way, particularly in basketball.”

One year into his tenure, Head Football Coach Bobby Johnson put the Commodores into the Music City Bowl, just the fourth bowl experience after 118 years of fielding a football team. A victory over Boston College had Music City whistling “Dynamite,” and to some, that mountain looked shorter.

However, this is the Southeastern Conference, not Hollywood, and nobody rode off into the sunset.

“We had a hiccup after 2008,” Williams says. “I don’t think many would have expected to go from a bowl game to 2–10 the next year. But in other areas we were making solid, tangible progress. We won our first national team championship in 2007 with our bowlers, we were strong with basketball and baseball, and we could see other programs coming on strong.”

Behind the scenes Williams saw progress, too, in the way university leadership perceived athletics. “The university began to understand the value we could bring to the overall experience,” he says. “It took time for some to understand that just because we were getting better didn’t mean [the overall Vanderbilt experience] was getting worse.”

As Zeppos recalls, when it came time to hire a new head football coach, “I sat with my good friend David Williams and said, ‘Let’s focus on getting a great coach and make the investments to win the Vanderbilt way and become a shining star for college athletics. We’ve done it in baseball, women’s basketball, men’s basketball, golf, lacrosse. I know we’re in the SEC. I get football. But we’re competing at the top level with every other school. So we’re going to do it. We’re going to hire the coach.”

James Franklin was the fourth head coach candidate to be interviewed by Zeppos and Williams.

“I had talked to a few athletic directors before, and someone had advised me, ‘Get a leader who’s a coach—not a coach who’s a leader,’” Zeppos remembers. “James looked right across the table and said, ‘I have a plan, and here’s how we are going to win.’ He is a gifted individual who inspires young people to be great students and great athletes.”

A Large Mountain to Climb

Few fans today may have been there to witness it, but this isn’t the first time Vanderbilt has enjoyed such success. During the heyday of the legendary Dan McGugin, football coach from 1904 to 1934, Vanderbilt was a gridiron powerhouse. Dudley Field, built in 1922, was the largest stadium in the South. Future football Hall of Famers routinely chose to attend Vanderbilt.

Vanderbilt basketball gradually became Nashville’s “in” thing after World War II, especially after Memorial Gymnasium was built in 1952. A progression of stars, from Billy Joe Adcock (BE’50) to Clyde Lee (BA’70) to Perry Wallace (BE’70) to Jan van Breda Kolff (BA’74) and the F-Troop, entertained and inspired sports fans for 25 years.

Wallace, a Nashvillian who would become a distinguished lawyer, scholar and Hall of Famer himself, broke the SEC basketball color barrier in 1966. He had clear reasons for selecting Vanderbilt over the scores of scholarship opportunities available to him.

“The first reason,” Wallace says, “was its combination of a fine educational institution with big-time athletics. Second, when I went to visit some of the schools I had dreamed about attending, I noticed the black athletes didn’t appear to be fully integrated into the campus life and often were not in pursuit of a serious academic degree. It felt like a new plantation system. And third, my parents could come to the fancy part of town and people treated them nicely. They were shown the respect they deserved, and selecting Vanderbilt was my way of giving something back to them.”

Football, however, was the bell cow of the SEC, which included Vanderbilt as a charter member in 1933. Football Saturdays defined how many regarded a university.

That was at odds with how Vanderbilt defined itself. Many years ago Dean of Students Madison Sarratt told his classes, “Today I am going to give you two examinations, one in trigonometry and one in honesty. I hope you will pass them both, but if you must fail one, let it be trigonometry, for there are many good men in this world today who cannot pass an examination in trigonometry, but there are no good men in the world who cannot pass an examination in honesty.”

Academic excellence had been and will forever be at the foundation of Vanderbilt’s core principles. And so a false debate ensued: Could one be Harvard from Monday to Friday and Alabama on Saturday?

With this as a backdrop, Title IX was born in 1972. The federal government realized young women were not getting anywhere close to an equal opportunity in collegiate athletics and mandated that universities change their chauvinistic ways. Most nodded agreement, but athletic directors gulped, understanding that new revenue streams must be found to fund women’s programs.

The early 1970s brought unequal women’s programs into being. Gifted student athletes and future Vanderbilt Athletic Hall of Famers Ann Price, BA’71, MD’78 (tennis) and Peggy Harmon Brady, BE’72 (golf) helped blaze a trail for future women to follow.

“I never felt like we were under-resourced,” says Price, despite traveling to meets all over the South in a station wagon and, on occasion, witnessing the university unable to afford sending a full squad to an elite tournament. Price would have been a coveted basketball recruit had there been opportunities for women. Seeing only limited choices, she picked Vanderbilt for academics and became a tennis star—and, later, a medical doctor. Today she is associate dean for alumni affairs and associate professor in the Vanderbilt School of Medicine.

When Roy Kramer settled in behind his desk as Vanderbilt’s new director of athletics for the first time on Labor Day, 1978, he knew the job was going to be an uphill climb. With brief exceptions, the football program had sputtered since the end of the Great Depression, the proud men’s basketball program was transitioning from the glory days of Roy Skinner into a period of controversy, a fledgling women’s program would need financial and moral support, and the athletic plant was, for the most part, an eyesore.

“I was well aware we had a fairly large mountain to climb,” Kramer remembers. “It was a daunting challenge, particularly in football, to develop the program to competitive status. What impressed me the most, however, was how much people inside the university did care about having a proud program—not that they expected championships but to be competitive. That outweighed any of my reservations.

“The outside world thought the university administration was anti-athletics, and that was not the case. People such as Chancellor [Alexander] Heard, President [Emmett] Fields and [Vice Chancellor] Rob Roy Purdy really did care, as did Board of Trust members such as Sam Fleming [BA’28]. They were very supportive. We knew we were not going to do this overnight, but it gave us hope that the challenge could be met.”

During the next two decades, the Commodores had their moments, such as in 1993 when the women’s basketball team was rated No. 1 for six weeks and made the school’s only Final Four trip. The same year Coach Eddie Fogler’s men’s team won the SEC and was ranked as high as third.

Fogler, whose son Ben is currently a member of Vanderbilt’s golf team, believes athletics plays an important role on the campus. Indeed, his championship team had high academic achievers such as Bruce Elder (BA’92, MBA’93) and Kevin Anglin (BA’93) in its starting lineup, and he admits he would not have been as interested in Vanderbilt had it not been for its commitment to academics.

A Shift in Mentality

Twenty-five years after Kramer’s arrival, no one is more excited about gridiron success than Zeppos and Williams, who have spearheaded multimillion-dollar fund drives to improve athletic facilities across the board. Williams desires an all-around program of excellence and is as proud of his strong Olympic sport teams as he is his College World Series or SEC basketball rings.

People are paying attention, including John Skipper, president of ESPN and co-chairman of Disney Media Networks. “I had a chance to observe Vanderbilt athletics close up during the four years [2009–12] my son Clay was in school there,” Skipper notes. “Vanderbilt athletics is special. They compete at the highest level while insisting that varsity athletes remain real students. It is a great achievement. I think the media admire what Vanderbilt accomplishes at a medium-sized private school in a big, mostly public-school conference. I had a chance to see terrific baseball teams every year, very good women’s basketball teams, the men’s team beat Kentucky, and the football team beat Auburn (with ESPN’s College GameDay on campus!),” Skipper continues. “I thought that would be the highlight of Vanderbilt football forever but was proved wrong this past year. James Franklin is a great young coach.”

“I think the athletic department seems similar to the baseball program,” Corbin observes. “It has gained confidence. Nothing is more important than the shift of the mentality; that to me is the most important thing that has happened.”

Williams likes winning as much as anyone, but he sees a bigger mission. “I want us to be more a part of solving some of the issues that exist in the community. For example, it may sound self-serving to some who may think we are just trying to make a dollar, but I am thrilled we can soon host high school football and track. That helps the community.”

Commodore Nation feels good about itself. The dedication to academic excellence remains, and the program is still the only one in the Southeastern Conference never tainted by NCAA probation. There is more diversity (both racial and geographic), women are in leadership roles, and the department is active in the community.

Where discouraging jokes and bad karma once existed, a positive vibe now permeates. Fans who thought they never again could fall in love with the Commodores are rethinking their weekend plans and expanding their wardrobes to include more black and gold.

Perry Wallace agrees. “I have an active membership in a great institution, and that makes me feel good.”

Rod Williamson is director of communications for Vanderbilt athletics.

Read the latest news about Vanderbilt athletics at vucommodores.com. Also download the free official Commodores app for your Apple or Android device.