Julián Hillyer knows how to set mosquito hearts racing.

Although mosquitoes are the “vector” that spreads a number of infectious diseases including malaria, dengue and yellow fever, they possess a specialized immune system that fights off many undesirable invaders. The primary cells involved in the insect’s immune defense are located in its circulatory system and are pumped throughout the insect’s body by its hose-like heart. Despite its central role, scientists don’t know very much about how the mosquito’s heart works.

To begin answering this question, the assistant professor of biological sciences decided to investigate how the mosquito’s heart is regulated. He recruited his research assistant, Tania Estévez-Lao, and an undergraduate student, Dacia Boyce, to assist in the investigation. The team decided to test the effect of the peptide CCAP, which is known to regulate cardiac function in a number of other arthropods, including fruit flies and crabs.

In a series of extremely delicate experiments with live mosquitoes, they found that an injection of CCAP caused the mosquito’s heart rate to increase by nearly 30 percent, which produced a 33 percent increase in the flow rate of haemolymph, the mosquito equivalent of blood.

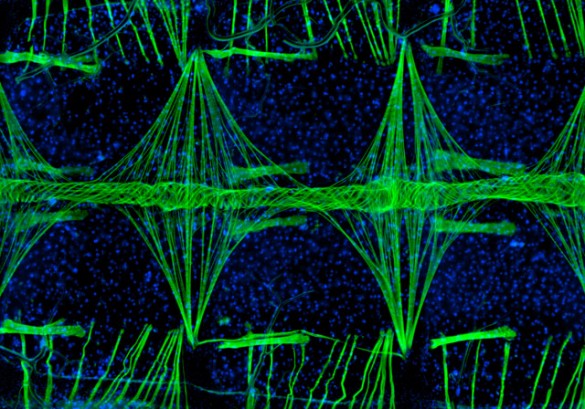

Having established CCAP’s regulatory role, Hillyer’s team decided to search out the region in the mosquito’s body where the molecule is produced. With the assistance of colleague Willi Honegger, professor emeritus of biological sciences, they were able to trace its primary point of origin to a specific set of neurons in the mosquito’s brain.

“This shows for the first time that the adult mosquito’s circulatory system is under partial control of the mosquito’s brain,” said Hillyer.

The research was published in February in the Journal of Experimental Biology and was funded by National Science Foundation grant number IOS-1051636.