They had just done a belly crawl in the Southport Saltpeter Cave in Maury County, Tenn., wriggling through a 90-foot-long shaft that was just a foot tall in some places, when Darrell Smith began acting strange.

He took his helmet off, which the experienced spelunker would never do underground, and kept shining his headlamp in his girlfriend Jessica Rogers’ eyes.

“I told him twice not to do that, but he wasn’t responding,” Rogers recalled. “He was disoriented and couldn’t talk. We tried to give him water and he spilled it.”

More than 1,000 feet underground, Smith was having a stroke.

There is a common saying with stroke that “time is brain” because the longer a clot in lodged in brain’s arteries cutting off blood flow, the more damage is done, including loss of the ability to talk and move.

Smith and Rogers have explored caves all over Kentucky and Tennessee. They know to never go caving with fewer than four people because if one is injured, one person can stay while the other two summon help. Rogers’ brother and best friend went to the surface while she held Smith on the cave floor.

“We sat like that for two hours. Time just slipped away. We were 1,000 feet under with just a headlamp. He stopped breathing three times. After the third time we had a little chat and I told him he had to hang on.”

The Maury County search and rescue team was able to strap Smith into a basket and sometimes carry, sometimes drag, and sometimes use a rope and pulley to get him to the surface. As a part-time firefighter for 20 years, Smith, 48, was calm and knew what to do, though he only has partial memory of it today.

He was intubated and put on a LifeFlight helicopter bound for Vanderbilt University Medical Center. It had been about five hours since his stroke began, and his time window for a good outcome was quickly closing.

“Getting to the hospital was the worst part for me. I had just been focused on getting him out of the cave and getting him in good hands, but then it hit that this was very serious,” said Rogers, who added that the spelunkers attracted a lot of attention covered head to toe in mud.

“The doctors did a good job of explaining bluntly that we were short on time and that, without intervention, in the best case scenario he would live in the state he was in now. It was a tense moment to make those decisions, but I knew there was no way he would want to live like that. I said ‘get going, get him to surgery.’”

Researchers at Vanderbilt are leading an international clinical trial to examine the functional benefits of an interventional device treatment, the Penumbra System, that gently suctions away blood clots to restore blood flow to the brain’s affected area, in addition to the clot-busting drug tPA (tissue plasminogen activator). The Penumbra System was approved by the FDA in 2007.

“The device works like a straw, it literally sucks the clot out,” said J Mocco, M.D., M.S., associate professor of Neurological Surgery and the study’s principal investigator. “In our recent experience at Vanderbilt, almost half of the treated patients return to being independent afterward. These are patients who otherwise would likely be devastated with severe disability.”

The standard of care in most stroke centers involves administration of IV tPA within three to four-and-a-half hours of the onset of symptoms. However, most patients do not arrive in time, and the treatment may fail if a clot is too large or difficult to dissolve. If this occurs, alternative minimally invasive, inside-the-artery clot removal can be used up to eight hours after onset of symptoms.

In Smith’s case, he was outside the tPA window and had two blockages — one in the carotid artery, the brain’s largest blood supplier, and one in the middle cerebral artery, which provides blood to the part of the brain that controls the right side of the body and one’s ability to speak and understand speech.

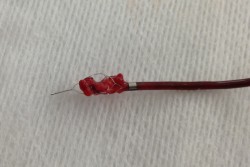

Entering through an artery in the leg, Mocco snaked the Penumbra device up to the blockage in the carotid artery and suctioned out the clot. He then used the Penumbra in combination with the newest device available to treat stroke, the Trevo, to remove the final clot.

“The Trevo looks like a chain link fence rolled up in a tube. We deploy it into the clot and it opens like a stent to restore blood flow. Then we wait a couple of minutes to get the clot really stuck in the stent, and then pull it out, with the Penumbra suctioning at the same time,” Mocco said.

With the severity of Smith’s stroke, there were no reservations about this interventional approach. But in other, milder strokes, some argue the risks outweigh the benefits.

“In the worst case scenario, this causes a hemorrhage, or bleeding in the brain. Therefore with more mild strokes, it’s a balance between possibly making the situation worse, but potentially making it much better. There always has to be an analysis of the risk,” Mocco said.

“But I’ve seen the great outcomes and believe in this treatment. Five to 10 years ago those complications were more common, but now they are becoming rare.”

Smith spent two weeks in the hospital recovering. He immediately regained the ability to understand speech but had very weak movement on his right side and his speech was indecipherable.

These functions slowly improved and he is now speaking clearly and walking with a walker.

“It’s a miracle he made it out of the cave alive,” Rogers said. “I now realize it was very unlikely he would live, much less be up and walking around like he is. As with anybody, you can’t gauge how quickly the brain will heal itself, but he is doing so much better than expected.”

Smith works diligently at his physical and occupational therapy exercises because he has a goal:

“In 90 days, I’m going back to the cave to finish it.”