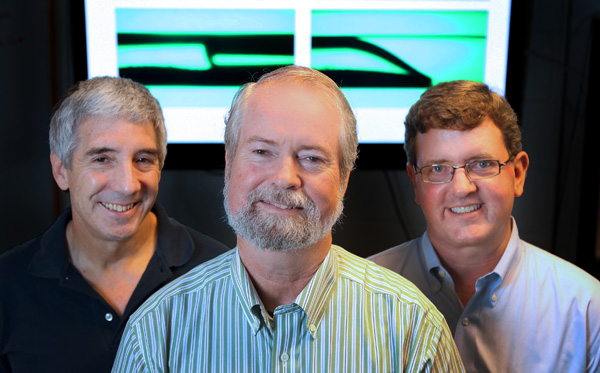

Last December a trio of Vanderbilt researchers — Rick Haselton, professor of biomedical engineering, David Wright, associate professor of chemistry, and Ray Mernaugh, associate professor of biochemistry — snagged a $1 million grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to develop a “low tech, high science” method for collecting and preparing the patient samples in under-developed areas. Haselton’s students dubbed the device the “Extractionator.”

We announced the grant in the story “‘Extractionator’ could bring high-tech medical diagnostics to rural areas.”

Five months ago, it consisted of little more than a length of plastic tubing, a large magnet and a handful of small magnetized beads. The project is described, more or less, in the June issue of Discover magazine.

But it is amazing what a happens when you combine handful of bright (intelligent and well-educated) minds and a million bucks! Although the Extractionator remains relatively low tech, in a few months the researchers have transformed it into a sophisticated little device that automates the sample collection and preparation process so it can be operated by individuals with a minimal amount of training.

One of the graduate students involved made a video of the prototype device and put it on YouTube:

Of course, the project involves a lot of science beyond the clever mechanical design shown on the videotape. On April 25, Wright was one of 20 malaria researchers from around the United States invited to present their research to members of the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate as part of World Malaria Day.

At the meeting, Wright reported that their tests have shown that the Extractionator not only purifies but it also concentrates biological samples in such a way that it increases the effectiveness of current commercial malaria diagnostic tests eight-fold. “These tests are not very effective because they lack sensitivity,” said Wright. As a result, about half the time anti-malarial drugs are given to people who don’t have malaria, a practice that allows malaria microbes to develop resistance to the drugs. “The Extractionator could ensure that only the people who have malarial are treated, which would extend the useful life of existing drugs for a longer period of time and would nearly double the number of people who could be treated with a given supply of drugs.”

The conference exposed Wright to some perspectives that differ substantially from those common to basic scientists, he found. One such point of view was an interest in how the investment in these technologies could contribute to strengthening the domestic economic infrastructure and create jobs at home, “So the fact that there is a global market of 25 million malaria diagnostic tests annually was important,” he said.

Similarly, the discussions included foreign policy implications. Global health initiatives represent less than 1 percent of the nation’s budget for foreign aid, but it is considered to be one of the most effective. “Since the first President Bush started added an anti-malaria program some countries have seen decreases in malaria mortality by 40 percent,” he said. “These are real numbers and they prompted the U.S. AID administrator to describe the anti-malarial programs as the ‘tip of the spear’ that can make big inroads quickly.”

“We’re really happy to be involved,” said Wright, before flying to Seattle for a Gates Foundation review of the project.