The Owen Graduate School of Management’s David Owens examines why some great innovations fail

“Creative people must be stopped!”

We may not actually hear these words spoken aloud in the weekly staff meeting, but sometimes it feels like an underlying corporate message. In many work groups, innovative ideas are aggressively shot down, quietly undermined or simply left to wither and die on the vine. Some people water down their ideas or choose not to share them in the face of potential criticism. There are lots of reasons why a brilliant idea is grounded before it can take flight.

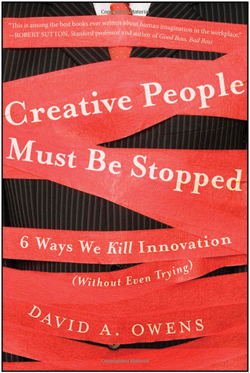

But creative thinkers need not despair; there are ways to circumvent toxic group dynamics, creativity-resistant managers and even self-sabotage so that quality ideas can flourish. So says Owen Graduate School of Management professor David Owens, whose new book, Creative People Must Be Stopped: Six Ways We Kill Innovation (Without Even Trying), draws from his years of experience as a consultant for NASA, Apple Computer, Daimler Benz, LEGO and many more.

“I have observed corporate environments where people were throwing Nerf footballs at all hours of the day and night, and it seemed like total chaos. But these great ideas were coming out of it, so I studied that,” Owens said. “What was the thing that made it work? The Nerf footballs? The caffeine?

“On the other end of the spectrum, I’ve observed many, many meetings at organizations where great ideas were abandoned because people were afraid to speak up. It was a tough crowd and they knew they were going to get shot down.”

A common creativity-dooming scenario, Owens said, is when a supervisor engages a worker to come up with the next big idea, telling him or her, “Be creative – think outside the box.”

“You hear that and you get excited about the opportunity,” Owens said. “You come up with this great idea and you can’t wait to tell the boss about it. But instead of liking the idea, he or she tells you it’s too expensive or too weird. Then you’re back at square one.”

Embracing criticism instead of seeing it as failure is the first step to overcoming the sting of having your idea questioned or criticized, Owens said. Use that feedback, if you can, to make the idea better.

“[lquote]If you have an idea, the world is going to try to stop it. Unfortunately, that’s just how things work,” he said. “But if you approach it strategically and present the idea in an engaging way, you are more likely to move it forward.[/lquote] If you hit a roadblock, you may need to change your process. Just don’t give up.”

Owens’ passion for innovation and his curiosity about how things work became evident as a toddler. By age 3, he was disassembling toys and household gadgets to see what was inside. By 10, he was creating his own electrically charged inventions.

“Disco was big at the time, and I vividly remember having this cardboard box that I hooked up to the stereo so that the lights inside the box would flash in time to the music,” Owens said. “My dad saw it and went crazy. He thought I was going to burn the house down.”

With his father in the Army and stationed in Germany, Owens moved around a lot. The family lived in several German cities during his childhood, including Munich and Heidelberg, and Owens learned to speak fluent German in addition to English. Ultimately, his bent for engineering brought him to America – Stanford University, in particular – where he earned a bachelor of science degree in electrical engineering in 1987, a master’s in engineering product design in 1993 and a Ph.D. in management science and engineering in 1998.

He came to Vanderbilt more than a decade ago to teach young MBA-seekers about strategic innovation, new product design and development, and organizational design. His lectures and workshops, based on his real-world experiences, were the impetus for Creative People Must be Stopped, which was published last fall by Jossey-Bass.

He came to Vanderbilt more than a decade ago to teach young MBA-seekers about strategic innovation, new product design and development, and organizational design. His lectures and workshops, based on his real-world experiences, were the impetus for Creative People Must be Stopped, which was published last fall by Jossey-Bass.

One of the most surprising conclusions the book makes is that the greatest adversary a creative person may face will be him or herself.

“We are still talking about Leonardo da Vinci’s ideas 400 years later,” Owens said. “That’s because he expressed them so well. There are probably lots of other people who have had equally great ideas, but they weren’t expressed in a way that engaged us so we don’t remember them.”

Owens – an author, teacher, engineer, consultant and idea facilitator – admits his own ideas aren’t always good, especially when it comes to small projects around the house.

“I have destroyed far more things of value than I’ve made or put back together,” he admitted. “But within the last year or so, I’ve come to terms with that. I break stuff and I’m fearless about making stuff and I’m OK with it. That’s the way great ideas are born.”

Watch David Owens discuss “Six Ways We Kill Innovation Without Even Trying.”