Amy-Jill Levine explores the shared heritage of Christianity and Judaism

Amy-Jill Levine was always fascinated by Christianity. She recalls singing Christmas carols in public school in North Dartmouth, Mass.; joining friends to trim Christmas trees and hunt for Easter eggs. Then a schoolmate accused her, “You killed our Lord.”

That confrontation was life changing. Levine couldn’t understand why a Christian would hold her personally responsible for murder. And thus began her fascination with the common roots of Judaism and Christianity.

“My parents had a very open attitude toward other religions,” said Levine, University Professor of New Testament and Jewish Studies at Vanderbilt. “When I asked to learn more about Christianity, to learn why Jews were blamed for the death of Jesus, they encouraged me to explore.”

Levine fed her curiosity by sitting in on religious education classes and attending Mass with her Portuguese Roman Catholic friends.

“I never heard anything negative there about Jews,” she said. “Then in high school, I read the New Testament, and I realized the source of the problem.” But she also realized that reading the New Testament does not have to lead to anti-Jewish sentiments – that it actually provides excellent insight into Jewish history.

“We choose how to read,” she said. “Moreover, the New Testament covers a period that is generally overlooked in synagogue educational programs.”

After receiving her bachelor’s degree in religion and English from Smith College, Levine earned a master’s and doctorate in New Testament studies from Duke University. She also now holds five honorary doctorates.

In 1995, Levine, who had been teaching at Swarthmore College, joined the Vanderbilt faculty. She was soon named the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Professor of New Testament Studies.

“When I was appointed to the faculty, both Jews and Christians were concerned,” she said. “Some people thought I was a Messianic – that is, a Jew who worships Jesus as Lord and Savior – who saw Judaism without Jesus as illegitimate. Others were afraid I was out to undermine the Christian faith.”

Then-Dean of the Divinity School Joe Hough held a reception so that the Vanderbilt and Nashville communities could meet Levine in person. “[rquote]Everyone ended up being welcoming and enthusiastic once I had the opportunity to explain what I do,” she said.[/rquote]

Levine holds faculty appointments in the Divinity School and the College of Arts and Science in the Program in Jewish Studies. One of her primary research interests concerns how people from different traditions can read the same biblical text and come up with dissimilar meanings.

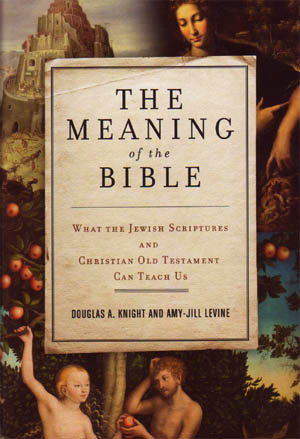

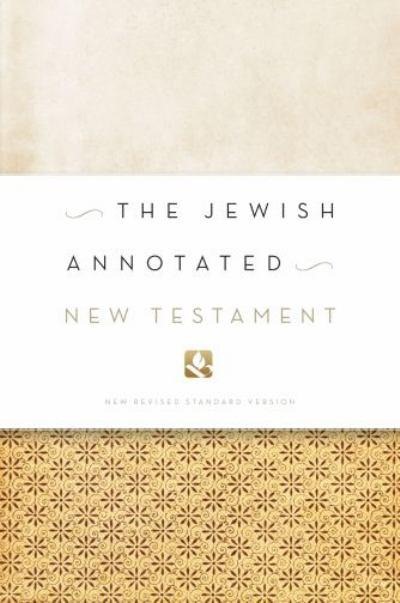

Among the fruits of her research are two books published this past November: The Meaning of the Bible: What the Jewish Scriptures and the Christian Old Testament Can Teach Us (HarperOne), co-authored with her Vanderbilt colleague Douglas Knight; and The Jewish Annotated New Testament (Oxford University Press), which she co-edited with Marc Zvi Brettler of Brandeis University.

Among the fruits of her research are two books published this past November: The Meaning of the Bible: What the Jewish Scriptures and the Christian Old Testament Can Teach Us (HarperOne), co-authored with her Vanderbilt colleague Douglas Knight; and The Jewish Annotated New Testament (Oxford University Press), which she co-edited with Marc Zvi Brettler of Brandeis University.

The Meaning of the Bible is a thematic introduction to the scriptures of Israel. “Doug and I sought to introduce readers to the Bible’s diverse presentations of such subjects as politics and economics, gender and sexuality, and the beginning and end of the world,” she said. “We look both at how the texts would have sounded to their original audiences and how readers today – Jewish, Christian or of no religious identification – understand them. We also look at what events and figures can be confirmed historically.”

The Jewish Annotated New Testament, which is published using the New Revised Standard Version translation, provides not only the standard annotations found in any academically oriented Bible, but also details about how the New Testament writings fit within their original Jewish contexts.

The Jewish Annotated New Testament, which is published using the New Revised Standard Version translation, provides not only the standard annotations found in any academically oriented Bible, but also details about how the New Testament writings fit within their original Jewish contexts.

The project, which involved 51 Jewish scholars, addresses negative, erroneous stereotypes, such as the notion that the synagogue promotes the retributive violence of “an eye for an eye,” whereas the church promotes the restorative justice of “turning the other cheek.”

“The rabbis interpret ‘an eye for an eye’ in terms of monetary payment, not bodily mutilation,” she explained. “[rquote]The volume shows Jews and Christians our common roots as well as the reasons why we came to separate.”[/rquote] Levine said that there was negotiation between the contributors and the editors. “There were places where we disagreed with an annotator, and there were instances where Marc and I disagreed with each other,” she said. “But we wanted to show the diverse ways that scholars today understand the text.”

Some of the most notable differences of opinion in the annotations have to do with the apostle Paul.

“Some of the annotators see Paul completely embedded within Judaism, including the practice of Jewish law, and others view Paul as pulling away from certain Jewish traditions,” Levine said. “Readers can read what Paul said, read the annotations and then make up their own minds.”

Over the years, Levine has been asked to speak at more than 60 churches and five synagogues in Middle Tennessee, as well as hundreds of churches, synagogues, seminaries and universities on several continents.