While listening to a physics colloquium titled “Science: What the Public is Thinking, What Congress is Doing, How You Can Contribute” delivered by Michael S. Lubell, professor of physics at the City College of New York and director of public affairs for the American Physical Society (APS), I couldn’t help thinking about the fable of the grasshopper and the ants.

The old Aesop tale may have some relevance to the current political situation as the scientific community watches with considerable concern as Congress is swept by an unprecedented budget-cutting fervor.

It is not that the scientific community, aka the grasshopper, has spent its time singing and idling during good economic times. In fact, the nation’s scientists have been extremely productive, making significant advances in genomics, nanoscience and technology, neuroscience, materials science, ecology, computer science and cosmology, among many other areas. And it is certainly not the case that the American public, aka the ants, has been extremely frugal and salted away a lot of money to weather the current economic downturn.

What does appear relevant has been the attitude of the scientific community which has generally taken public support for granted and so hasn’t made a satisfactory effort over the years to explain the importance of basic scientific research to John and Jane Taxpayer in ways that they really understand. Now that economic times are really tough, this oversight has put government funding for scientific research in serious jeopardy.

“We’ve ignored the public in the past. If we ignore the public in the future we do so at our own peril,” Lubell warned the small campus audience which attended his talk.

“Until the last election, we were having tremendous success in getting political support for science,” explained the government-affairs veteran. Science supporters had marshaled considerable political backing for the America COMPETES Act, which called for significant increases in the research budgets of the National Science Foundation, National Institute of Standards and Technology and the Department of Energy. President Bush signed the original bill into law in 2007 and the reauthorization was signed by President Obama in Jan. 2011. However, the election of 2010 proved to be a political sea change. No longer did reasons like ensuring the nation’s international competitiveness resonate with Congress in the way it had in the past.

“We decided that we needed to know what the public thinks about science and government support of science,” Lubell explained. A number of scientific and higher-education organizations including the APS banded together to fund a pair of public opinion pollsters – one Republican and one Democrat – to conduct a national internet survey of 1,200 people.

The good news from the survey is that a majority of the public still believes that the United States should be the world leader in science and rates scientists as more trustworthy than lawyers, politicians and journalists. According to the polling about two-thirds say that it is appropriate to use taxpayer money to support scientific research. Even a slight majority (54 percent) of self-identified members of the Tea Party agreed.

“The bad news is that the public has no idea why supporting scientific research is a good thing,” said Lubell. As a result, when people are forced to make a choice, they rank science with defense as the two areas they are most willing to cut. Conservatives prefer cuts in science over those in defense while liberals prefer cuts in defense over those in science.

When push comes to shove, in fact, fully fifty percent of the survey respondents supported cutting the federal science budget by 22 percent ($140 billion over 10 years) and 50 percent opposed it, Lubell reported. “Interestingly, these opinions were quite fixed. When the benefits of supporting science were explained to them, people didn’t change their minds,” he said.

Fortunately, public anger is not focused on the scientific community, it is directed at the government, Lubell emphasized. In the survey, 46 percent of respondents gave the federal government a grade of C, D or F for its efforts to promote technological innovation and 50 percent believed the federal science budget is too large.

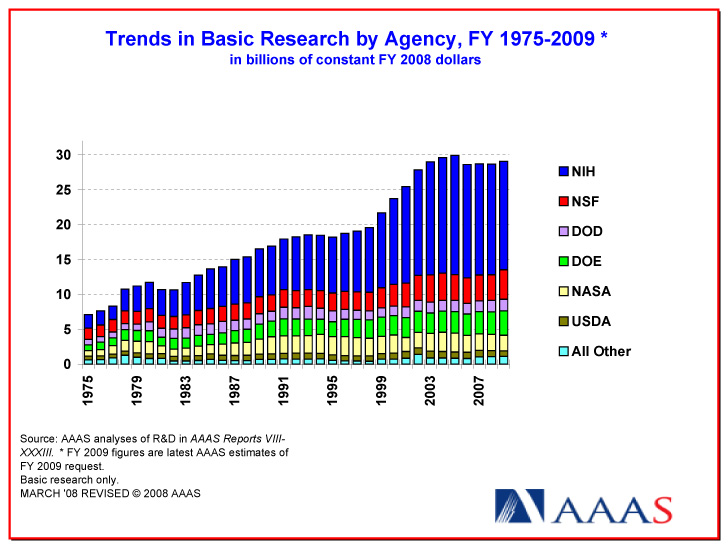

One underlying problem is that the scientific community has allowed itself to become isolated from popular culture. Americans are surrounded by the fruits of scientific and engineering research to an unprecedented degree, yet only a small minority has any idea of how science works and what scientists are like. Nor do they appear to have any idea of how great an impact scientific research has had on their lives. For example, most voters do not realize that discoveries in basic research laid the groundwork for about half of the economic growth that the United States has experienced since World War II in areas such as aerospace, computers, internet, cell phones, advances in medical treatment, etc. Many of these advances were made in the 1960’s and 70’s when the level of government funding for research as a percentage of GNP was about twice what it is today.

“Steve Jobs was a brilliant man,” said Lubell, “but his accomplishments were based on the work of many basic scientists supported by government grants.”

The polling data suggest that the road ahead will be rocky and scientists must find far more effective ways to engage the public. Lubell and some of his colleagues hope to put together a major media campaign for this purpose. It will be designed to get more telegenic scientists on shows like Letterman and Leno and Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert where they can represent the scientific community in new and interesting ways. At the same time, he urges rank-and-file members of the scientific community, particularly graduate students, to become politically active.