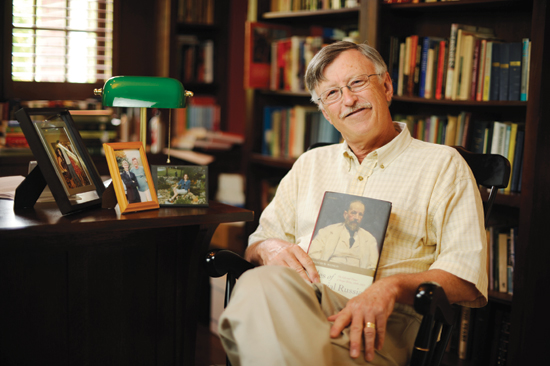

Frank Wcislo examines how we consider Russia and its leaders two decades after the Cold War

As Soviet Russia disintegrated in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Frank Wcislo and other Russian historians had a problem.

When President Reagan’s “evil empire” was no more, it was harder to get people to care about Russian history. Funding for Russian studies started to dry up. Enrollment declined. Russian studies faculties across the country faced cutbacks.

Wcislo, associate professor of history, summed up his dilemma like this: “If I’m not describing the enemy any more, then what am I doing?

“Historians aren’t supposed to be operating in terms of the present dictating the interpretation of the past, but we’ve learned from a whole series of postmodern developments that that is one thing that starts to happen,” he said.

The upshot? Wcislo’s ongoing work with the memoirs of Sergei Witte, a major power broker in Imperial Russia, morphed from a straight biography to something different. Biography still had its place, but more amorphous issues – gender, culture, the shaping of identity – were just as urgent.

Witte (1849-1915), with time on his hands after being pushed out of power late in life, wrote more than 3,000 pages of memoirs in two separate manuscripts. Wcislo notes that he frequently rambled away from the strictly biographical into long diversions. “First I marked them as ‘tangents,’” he said. “Then I just marked them as ‘vents,’ because that’s what they were.”

Among the “vents” were discussions of Jews that border on anti-Semitism and a rather fervid appreciation for the physique of a male colleague.

“He was a man of enormous size, with shoulders almost a sazhen (2 meters) wide, and he had a waist that any young woman would envy,” Witte writes in one of his memoirs. “I well remember his face because its extreme paleness stunned me.”

Such digressions don’t mean Witte was homosexual, Wcislo said, “but it is interesting to explore masculinity and homoeroticism in that time and place.” He also doubts that Witte was anti-Semitic, but says Witte’s comments about Jews give us “a window into the prevailing attitudes of Russians in the 1870s and how they interacted with Jews in the decade after the abolition of serfdom.”

Wcislo’s Tales of Imperial Russia: The Life and Times of Sergei Witte, 1849-1915 does not neglect Witte’s biography and accomplishments. His construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway, conversion of Russia to the gold standard and visit to America to negotiate the Treaty of Portsmouth are all covered.

“[rquote]Think of the imaginative power it took for a man who styled himself a philosophical mathematician to work on the railroad, which as a technology was the Internet of the 19th century,” Wcislo said.[/rquote] “In a time when Russia was still the most backward of the great powers, one railroad track allowed Witte to imagine a Russia that would be powerful, developed and industrialized.”

Interesting contradictions abound in Witte’s life story. Despite being a dedicated monarchist, Witte was influential in persuading the tsar to part with unrestricted power, create the Duma (the Russian Parliament) and allow a set of fundamental laws to be written and put into effect. Witte was obsessed with power yet believed in the ability of humans to peacefully change the status quo.

“He was a gigantic risk taker,” Wcislo said. “His modernization plan for Russia was a gigantic throw of the dice. He was able to see issues broadly and couple that perception with action. … He was an amazing intellectual power.”

In the United States, Witte has often been compared to Mikhail Gorbachev, who instituted massive economic and political reforms while serving as the last head of state in the USSR. But Wcislo found a much more intriguing comparison with contemporary Russia.

“If you go to Russia today, they don’t want to talk about the Soviet Union at all,” Wcislo said. “They’re enamored with the idea that today’s Russia is an extension of the world that existed and was somehow artificially interrupted by the revolution of 1917.”

Wcislo’s first interview about the book was with a Russian news agency that wanted his comments on how Witte’s approach has a lot in common with the “more entrepreneurial, capitalist economy of the present-day Russian federation.”

“People in the United States are obsessed with Putin and his authoritarian style of leadership, which Russians think is terribly provincial of us,” he said. “The press is less free and the government is authoritarian again. This doesn’t shock Russians at all. It shocks Americans.”

In the end, Witte was “devoured” by the authoritarian system he thrived in for so long, Wcislo said.

“They drove him into exile and deprived him of the elixir (power) he craved,” Wcislo said of Tsar Nicholas and his wife Alexandra, the last Russian monarchs. But Nicholas and Alexandra were toppled from the throne and murdered in the Russian revolution in 1917, two years after Witte died peacefully.

“So who had the last laugh?” Wcislo asked.

Video of Frank Wcislo speaking on Russian history is available at the Vanderbilt News site.