Stormy Weather tracks evolution of African American marriages

Stormy Weather tracks evolution of African American marriages

Long-neglected love letters between a domestic servant husband and his teacher wife have provided an important part of a new book that tracks how middle class African American marriages evolved in the early and mid 20th century.

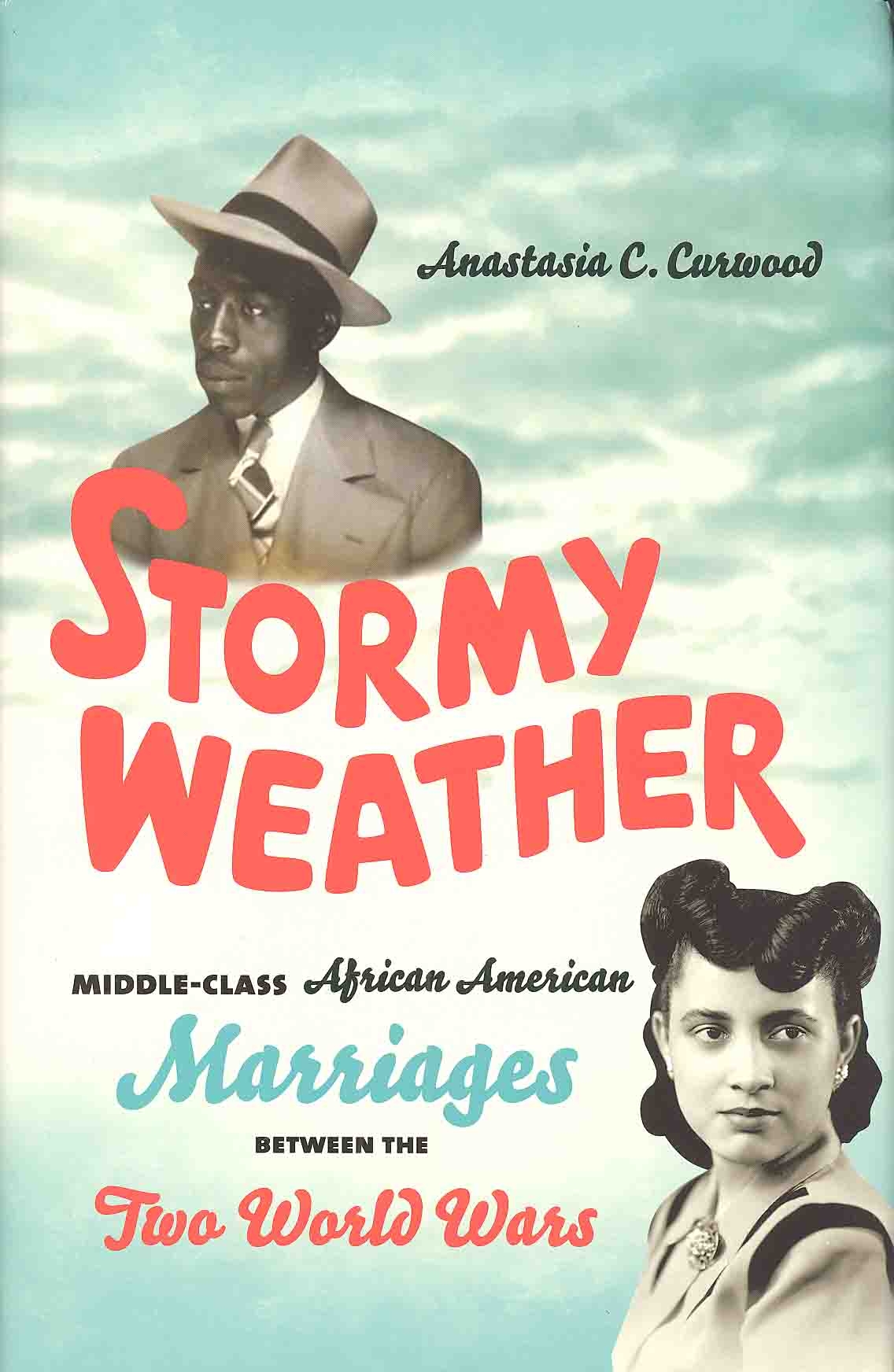

Stormy Weather: Middle-Class African American Marriages between the World Wars, published by The University of North Carolina Press, was written by Anastasia C. Curwood, assistant professor of African American and Diaspora Studies at Vanderbilt University. The book documents the strains that developed in African American marriages as the early civil rights and sexual revolutions played out.

“Around the turn of the century, the big concept was respectability – chastity and piety in women, breadwinning and restrained manliness in men,” Curwood said.

But mass migration of black Americans to the north along with evolving political and sexual mores complicated matters, she found.

“What they came up with is that men should continue to fulfill their breadwinning roles, but that things like emotional and sexual fulfillment in marriage were more OK,” Curwood said. “They were OK as long as women were remaining in their place. But some women weren’t content with that, and wanted to get out in the workplace and do civil rights work.

“It was just a complete mess, and it so happens that some individual couples got caught in this mess and had to figure it out on their own.”

James and Sarah Curwood – Anastasia Curwood’s paternal grandparents – were one of those couples. When Anastasia was in college, her aunt found a stash of correspondence between the couple in a New Hampshire farmhouse where Sarah Curwood once lived.

The letters tracked a relationship in peril because of Sarah Curwood’s desire to pursue education, a career and public activism, and James Curwood’s hope that she would be a more traditional wife.

“His (James Curwood’s) model of a good marriage and a proper family was from what he learned serving people as a butler and other service jobs,” Anastasia Curwood said. “[rquote]He didn’t understand that a lot of black women in the 1920s and 1930s were trying to make forays into professional work and civil rights work.[/rquote] He didn’t see that as appropriately womanly.”

The strain aggravated mental illness that was already plaguing James Curwood, Anastasia Curwood believes.

“Trying to live up to a perfect ideal can be very destructive,” she said. “In my grandparent’s case, not living up to that ideal would trigger my grandfather’s mental illness. … He was very concerned about who she should talk to, where she should work, how she should behave, how she should keep the house.”

The story of James and Sarah Curwood ended badly. After many affairs and a penchant for alcohol that damaged their relationship, James Curwood committed suicide.

Stormy Weather also documents other couples who better coped with these societal changes, the perspectives of African American leaders of the time and how popular culture reflected the changes.

“It’s taken a long time for us to really grapple with the full humanity of African Americans.” Curwood said. “Unfortunately, it has been a long time coming for scholars to look into the black people’s private lives and the larger social justice implications they bring up.”

To request review copies of Stormy Weather, contact Laura Gribbin at The University of North Carolina Press at Laura_Gribbin@unc.edu.