When Walter Ziffer applied to Vanderbilt University in 1949, he was a 22-year-old man with only six years of formal education and six high school credits on his transcript.

Ziffer’s youth had allowed little room for childhood, let alone school. The Nazi war machine overtook his town in Czech Silesia at the start of World War II. When Ziffer emerged from the war, having survived seven slave labor and death camps, he was 18 years old and weighed 87 pounds.

His body, he says, healed long before his spirit did, but he was determined to reclaim his life. In 1948 he left Europe to live with an uncle who had escaped to Nashville before the war. He quickly enrolled in high school, graduating in less than a year. Ziffer then appealed to Fred Lewis, dean of Vanderbilt’s engineering school, to take a chance on him. Lewis did.

Ziffer, BE’54, believes his education transformed his life. Inspired by his liberal arts courses–he still talks about the spark he felt in Professor Samuel Stumpf’s philosophy classes–he went on to graduate from Vanderbilt and then earned advanced degrees from the School of Theology at Oberlin College and from the University of Strasbourg.

“Vanderbilt was a life-changing experience for me,” he says. “It is a sad fact that after World War II, many survivors of the Holocaust were not able to put their broken lives back together because of the damage inflicted upon them by their Nazi captors and torturers. I have been one of the lucky ones.”

Ziffer was one of more than 300,000 Jewish Europeans who made their way to the United States between 1933 and 1952. Some had escaped Germany’s reach before the war broke out. Others had been forced to fight for their lives in the crucible of the Nazi genocide. Many were young people whose childhoods had been destroyed by war. But for Ziffer and others, despite all obstacles, education remained a cherished goal and a crucial step on the path back to a better life.

Each year fewer and fewer Holocaust survivors and refugees remain to tell their stories. We thank the alumni interviewed here for sharing theirs. In the face of cruelty and destruction, they chose to create and rebuild. Pushed toward despair, they sought meaning. Through their commitment to education, they answered barbarity with civilization. We also thank the Tennessee Holocaust Commission and the Western North Carolina Center for Diversity Education for sharing many of the photos that accompany this piece.

“You were supposed to surrender and be killed, but I didn’t follow the rules.”

On a shelf across from his desk, Max Notowitz keeps a photograph taken in Kolbuszowa, Poland, more than 70 years ago. It is of his cheder, the Jewish religious school he attended in the afternoons. Notowitz, about 9 years old, sits smiling in the middle of the first row. There are several dozen boys and teachers around him. Only four, including Notowitz, survived the war.

Notowitz still can repeat from memory religious lessons he learned as a little boy. He remembers reciting them while perched on his father’s arm.

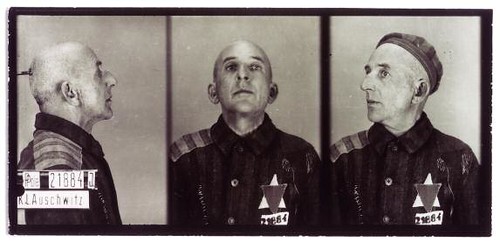

Notowitz is matter-of-fact as he talks about this, as he is when he holds out a picture of his father taken at Auschwitz. Osias Notowitz was murdered there in 1941, one day after Max’s 14th birthday. Less than a year later, the Germans imprisoned Max in a labor camp and executed his mother, brother and sister at the Belzec death camp.

“I tell this story simply because it happened to me, and because I witnessed it,” Notowitz says. “I’d much rather it hadn’t happened to me.”

Notowitz’s story is overwhelming in sadness and cruelty. Yet he tells it gently, in a soft, kind voice. It almost defies belief that he could survive such horror with any impulse toward gentleness intact. In 1942, Notowitz escaped the labor camp with 41 other prisoners. Only eight lived through the end of the war. Many were murdered while foraging for food.

“I saved my life by devious means,” Notowitz says. “I didn’t follow the rules. You were supposed to surrender and be killed, but I didn’t follow the rules.”

After the war Notowitz worked hard to find a way out of Europe. He earned money as he could, again not following the rules. In 1947, using false papers, he secured a visa to the United States. Once in New York City, he worked at a handbag factory by day and studied at night. He was a 20-year-old in fifth grade.

“I asked myself, ‘How long do I have to be in fifth grade?’ Others encouraged me to stick with the factory work–that it was a steady, dependable living–but I noticed they did not want it for their children,” Notowitz says. “I had in the back of my mind a letter I got from my mother when I was in the camp. I think she knew she would never see me again. She wrote, ‘I hope to be able to see you again, but if the good Lord denies me that, I want you to do one thing for me. Promise me that if you have a chance, you will get an education.’ This thing stuck with me. My mother said education was the best way to make your way in the world. That was my dream.”

Notowitz held fast to this dream. He found a cousin in Memphis, Tenn., who took him in and sent him to private high school. Less than two years later, despite his lack of credits, he applied to Vanderbilt.

“At Vanderbilt nobody asked me where I came from, what I did. And I didn’t talk about it. But my work was recognized,” Notowitz says. He graduated in three years, a member of both the Phi Beta Kappa and Omicron Delta Kappa honor societies. “Vanderbilt gave me something that I really had to earn. By the time I graduated, I was established.”

Though their years at Vanderbilt overlapped, Notowitz never knew Walter Ziffer, who also survived the Holocaust as a teenage boy.

“I always wondered if there were other survivors at Vanderbilt,” Notowitz says. “I never met any.”

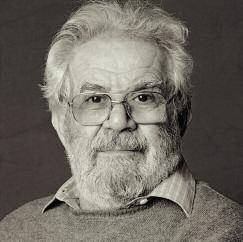

Notowitz found success in the insurance industry and, after a stint with U.S. military intelligence in Germany, settled down in Memphis with his wife, Fannie. They have four children and two grandsons. He has embraced his roles as philanthropist, active Jewish community member and Holocaust educator.

In 1997, Notowitz returned to Kolbuszowa with Fannie and his 14-year-old grandson. They went to visit the man who, on the night of the escape from the labor camp, turned to Notowitz and asked, “Are you coming?” After the war Notowitz gave this man, Janek, a photo of himself, writing on the back, “To the man who saved my life.” Janek still had the picture.

“When we got to the town, we had a lot of trouble finding his house,” Notowitz says.

“He’d met a Polish girl, converted, and become a sexton in the church. But when we finally found him, his granddaughter said to us, ‘You should have asked where the Jew lived.’

“He has died since then. With him died the last Jew in the town.”

“My father always told me, material things can be taken away, but what you have in your mind–no one can take that from you.”

Inge Smith believes that her father’s dedication to her education saved her life.

When the Nazi regime seized his silk wholesale business in Dresden, Germany, Walter Meyring no longer had a way to support his family. But he was just as devastated by her expulsion from school because she was Jewish. He resolved to leave Germany.

“My father raised me to believe that educaion was of foremost importance,” Smith says.

“What was going to happen to his child? My father’s friends–friends who had connections in the Nazi regime–told him it was not going to get better.”

Meyring had a nephew in the United States who sponsored the family. Two nights before they boarded a ship in Hamburg, in November 1938, Kristallnacht raged across Germany. During the rioting, thousands of Jewish businesses and synagogues were attacked. Tens of thousands of Jews were arrested. Meyring, who had gone to say goodbye to his mother, spent the night hiding in her apartment. He would never see his mother again; she was too old to qualify for a visa. Smith’s family learned after the war that to avoid deportation, she had been euthanized by a doctor and family friend. Most of Smith’s extended family died in Auschwitz.

The Meyrings arrived in New York City at Thanksgiving. The following Monday, Meyring enrolled his 15-year-old daughter in school.

Her father, once a successful businessman, took whatever work he could find. In order to go to the opera, which they had attended regularly in Dresden, her parents worked nights at the Metropolitan Opera. Her mother sold candy there.

“We came to the U.S. with $15 between us. That’s all they would let us take,” Smith says.

“The Council of Jewish Women helped us with so much. We would have starved to death without them.”

In the meantime, Smith became Americanized. She studied hard. She took her textbooks home, translated the lessons into German, did the exercises, and translated them back to English. After graduation she worked as a secretary and went to night classes at City College of New York.

Then she fell in love. “We had nothing in common,” Smith says. “Paul came from a farming community in western Tennessee. I was a big city girl.” Nevertheless, they married six weeks after he finished his Army service.

When Paul Smith took a job in Franklin, Tenn., his young wife panicked.

“I loved New York City. I adored my job. My family was there. All my friends were there. I loved going to school,” Smith remembers. “But my father said, ‘You are married now. You have to go.’ It was very hard.”

Smith spent her first few years having children and adapting to her new home.

“It’s a wonder they didn’t run me out of town,” she says. Her faux pas included going to the liquor store and taking her baby out for walks in the winter. “People would say to Paul, ‘You want to know what Inge did this time?’ They would say, ‘Oh my goodness, that poor foreigner.'”

Church was an important part of life in Franklin. Smith and her husband, who was not Jewish, joined a Presbyterian congregation, to which she still belongs. Smith remembers choosing it because she heard it had the best Sunday school in town.

Smith had left much behind in New York City, but not her passion for education. In 1952 she founded Franklin’s first kindergarten in her church’s basement. She took her own children to work with her.

“None of us had any money,” Smith remembers. “Families only had one car. I learned to drive so I could go around town picking up children for school.”

In 1958, after Inge’s mother died, Inge’s father came to live with her family. He helped her to build a small school adjacent to her home. The bustling Smith Preschool, with lovely tree-shaded playgrounds in the backyard, still serves about 55 children a year.

Then, with money and babysitting, her father helped her return to college. She earned three degrees from Peabody College, including an educational specialist degree. Her career blossomed. She helped to launch Tennessee’s Head Start program and supervised early childhood educators across the region. She helped to establish Franklin’s Harpeth Academy, an elementary school that has since merged with a larger institution. Smith headed the school until her retirement in 1991. She loved her work.

“My father always told me, material things can be taken away from you from one day to the next, but what you have in your mind–no one can take that away from you,” Smith says.

“Going to Peabody was a very special time in my life. Without my father’s help, I couldn’t have gone back. My father saved my life twice. He fulfilled his promise to give his daughter an education so she could become the woman she was meant to be.”

“How can the rest of the world let this happen, stand by this obscenity of obscenities, reenacted hundreds of thousands of times?”

In the decades following World War II, Walter Ziffer wandered physically and spiritually.

His journey started in his hometown of Cesky Tesin, Czechoslovakia, where he, his parents and his sister reunited after liberation. All four had survived years in Nazi slave labor and concentration camps. Ziffer was 18.

“I was afraid of everyone,” Ziffer remembers. “Four years in the camps had really set me back. It was a rough time.”

By 1947, Ziffer knew he could not stay in Czechoslovakia. Communist takeover of the country was imminent, and the military draft loomed. Ziffer left for France, where he spent almost two years, all the while hoping to join his uncle in Nashville.

Not everything turned out as Ziffer planned. He made it to Nashville, and at Vanderbilt he became an engineer just as he had hoped. But he also began a spiritual journey that would estrange him from his uncle’s family and set him on a completely new path.

“My friend Burton Grant, whom I met in class, was going away to study. He asked me to move in with his mother to help take care of her in his absence,” Ziffer says. “Through Mrs. Grant I was exposed to the Churches of Christ, and I converted.”

Ziffer also married. He had met Carolyn Kinnard, BA’52, in an introductory social science class. After graduation they moved to Ohio, where he had taken an engineering job with General Motors, only to find himself drawn toward a life in the ministry.

“At GM I dealt in car parts, but through church contact I became interested in people, in educating,” Ziffer says. “I wanted to improve the world a little bit.”

Religious study also spoke to Ziffer’s profound need to make sense of what he had witnessed during the war.

In a Holocaust Remembrance Day speech he gave in Florida last April, Ziffer described in graphic detail a murder he had witnessed in the Brande labor camp:

“The blood streams in rivulets from the man’s mouth, nose, ears and body wounds. I see the man’s eyes being beaten from their sockets … The Kapos lift Rabinowicz from the blood-, urine- and excrement-drenched floor and carry him out. They dump the body into the coal bin. … I, 14 years old, stand there, unable to move, sick to my heart and stomach. My feelings? They have gone dead. I am paralyzed … ashamed, speechless, motionless …

“How can a 14-year-old, witnessing this unspeakable brutality, survive and then go on with his life, even though the picture of that murder often haunts him in waking and sleeping hours? How can the rest of the world let this happen, stand by this obscenity of obscenities, reenacted hundreds of thousands of times all around Germany and its occupied lands? And finally, question of questions, where was God in that moment at Brande?”

between the Nazi invasion of Czechoslovakia and deportation. George, whom Ziffer remembers

as “a lovely boy with big blue eyes,” died in a concentration camp.

After Ziffer completed two master’s degrees at Oberlin College’s Graduate School of Theology, he resumed his wandering, family in tow. Working as a minister and educator, he never stayed more than five years in one city. He took jobs in France, Belgium and the United States. In 1982 he retired with Carolyn to Nova Scotia. It did not last. They moved to Maine, where Ziffer continued research that he had started in Canada.

“I had become interested in anti-Semitism,” Ziffer says. “I’d run into it all the time in my years as a minister–not against me, but in front of me: anti-Semitic jokes, remarks about the Holocaust. I set out to do some research, which resulted in a book, The Teaching of Disdain, about New Testament attitudes toward Jews. And then I realized that my place was with the Jewish people.”

After more than 25 years as a minister, Ziffer converted back to Judaism and became active in synagogue life. He moved once more, in 1993, to a town near Asheville, N.C.

This year he will have lived there longer than he has lived anywhere else in his life.

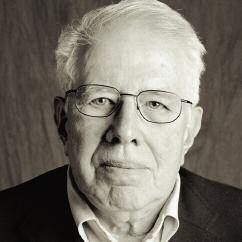

Now divorced and remarried, he turns 81 this year and continues to teach as an adjunct professor of Jewish studies at Mars Hill College in North Carolina. He published The Birth of Christianity from the Matrix of Judaism in 2000.

After years of study, teaching and searching, Ziffer seems to have found some of what he sought. At the end of his speech in Florida last spring, he was able to offer an answer to his question of questions about God’s presence in the world. He quoted a rabbinic interpretation of God’s words to Israel in the book of Isaiah: “When you are my witnesses, I am God. When you are not my witnesses, I am not God.”

“What does that mean?” Ziffer asked the audience. He answered with conviction. “The miraculous is for us to achieve. By witnessing to God–by practicing kindness, compassion, justice and love–we, you and I make God present. When, on the other hand, we turn our heads away in an effort not to see and not to get involved, God is truly absent.”

“Every night I doubted whether I would ever see my parents again.”

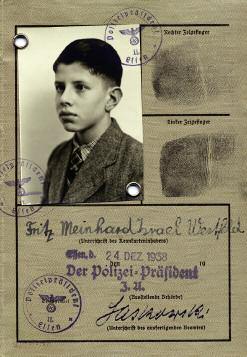

The realities of refugee life dampened Fred Westfield’s faith that he would attain a college education.

He and his family escaped Germany before World War II started, but not all at once. Westfield’s older brother, Erich, was the first to obtain a U.S. visa. He joined his uncle Robert in Nashville in 1936, when he was just 15.

In January 1939, 12-year-old Fred was sent to England as part of the Kindertransport, the famed rescue effort that relocated 10,000 German, Austrian and Czechoslovakian Jewish children to Great Britain in the late 1930s.

“Every night I doubted whether I would ever see my parents again,” Westfield says. He was placed with a foster family of Polish Jewish immigrants in London.

Westfield’s parents managed to secure visas to England in the summer of 1939. They were helped by money that Westfield’s uncle Walter had smuggled out of Germany. It was painful for them to have to use it.

“Uncle Walter was arrested two weeks after Kristallnacht. He was an art dealer, and they accused him of smuggling art and foreign exchange violations, because he’d been sending dollars to my uncle Robert in Nashville,” says Westfield. “He was tried, imprisoned, his art auctioned off to pay his fine.”

Walter was in prison for two and a half years. At the end of his sentence, the Nazis deported him to concentration camps. He died in the death chambers at Auschwitz.

Westfield and his parents were allowed to immigrate to the United States in 1940. They joined Erich in Nashville. Another of Westfield’s uncles, the artist Max Westfield, also escaped to Nashville with his wife and two children.

Nashville’s community of German Jewish refugees was small, but strong. Many were somehow related to each other and to families that had emigrated from Germany decades earlier. But life was difficult for Westfield’s father, Dietrich, who was already in his 60s. He had been a well-regarded lawyer before the Nazis rose to power. He had served as a judge advocate in World War I, for which he received the Iron Cross. In Nashville he was without a profession and penniless.

“He didn’t want to use my Uncle Walter’s money,” Westfield remembers. “How would you feel using your brother’s money–a brother who’s been imprisoned and later murdered? My father took odd jobs. He sold cola at the Mays’ hosiery factory. My mother worked, too.”

Westfield wanted to do his part.

“The summer before I turned 16, I took a job,” Westfield says. “There was a program where you could go to school an hour early and then get out in the afternoons to work, with the idea that you were learning a trade. My father–with all that was happening to us–I think he liked the idea of a Jew on the move learning a trade. I became a watchmaker and sold jewelry. I was good at it. I thought that is what I would become.”

The Army changed all that. Westfield served as an instructor at Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland, applying his watchmaking skills to the repair of optical instruments used in weaponry. After his service, Westfield used the G.I. bill–which included an extra stipend for those who were supporting parents–to go to college. He chose Vanderbilt, as had his brother, Erich, BE’43.

Like Erich, who had earned the Founder’s Medal for the School of Engineering, Westfield excelled. He completed his economics degree, magna cum laude, in only three years. He did his graduate work at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, studying with some of the greatest scholars in the field, including Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow.

After earning his Ph.D. there, he became a professor at Northwestern University. In 1965 he accepted a professorship from his alma mater and came home to Vanderbilt. Now retired, he is professor of economics, emeritus.

Besides Fred and Erich, who lives in Oklahoma, there were others in the family who came to Vanderbilt, too–their cousin Hannah Westfield Kahn, BA’48, who lives in New Jersey; Hannah’s late husband, Charles Harry Kahn, BA’46; and another cousin, the late Gerd Michael Westfield, BA’49.

Dietrich Westfield, who was an intellectual at heart–in his 70s, he started reading the classics in Greek–was proud of his sons’ academic and professional achievements. He had lost much in the war. But his sons had found their way in a new country.

Vanderbilt’s Holocaust Lecture Series

Each fall Vanderbilt invites the community to participate in

what has become the longest-running Holocaust lecture series

at any American university. Begun in 1977 by Beverly Asbury, then Vanderbilt University chaplain, it provides a forum for diverse perspectives on the Holocaust and other genocides.

Find out more:

www.vanderbilt.edu/religiouslife/holocaustlectures.html