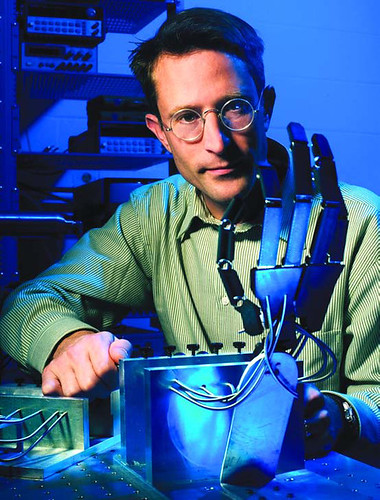

Combine a mechanical arm with a miniature rocket motor, and the result is the closest thing yet to a bionic arm.Vanderbilt mechanical engineers have developed a radically designed prototype as part of a $30 million federal program.

“Our design is closer in terms of function and power to a human arm than any previous self-powered prosthetic device, and it weighs about the same as a natural arm,” says Michael Goldfarb, the professor of mechanical engineering who is leading the effort.

The prototype can lift (curl) about 20 to 25 pounds–three to four times more than current commercial arms–and can do so three to four times faster. The mechanical arm also functions more naturally than previous models. Conventional prosthetic arms have only two joints, the elbow and the claw. The prototype’s wrist twists and bends, and its fingers and thumb open and close independently.

The Vanderbilt arm is the most unconventional of three prosthetic arms under development by a Defense Advanced Research Project Agency (DARPA) program. The other two are being designed by researchers at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore who head the program. Those arms are powered by batteries and electric motors. The program is also supporting teams of neuroscientists at the University of Utah, California Institute of Technology, and the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago who are developing advanced methods for controlling the arms by connecting them to nerves in the users’ bodies or brains.

“Battery power has been adequate for the current generation of prosthetic arms because their functionality is so limited that people don’t use them much,” Goldfarb says. “The more functional the prosthesis, the more the person will use it and the more energy it will consume.” Increasing the size of the batteries is the only way to provide additional energy for conventionally powered arms, and at some point the weight of batteries becomes prohibitive.

It was the poor power-toweight ratio of batteries that drove Goldfarb to look for alternatives in 2000 while working on another exoskeleton project for DARPA.He miniaturized the monopropellant rocket-motor system that is used by the space shuttle.His adaptation impressed Johns Hopkins researchers, so they offered him $2.7 million in funding to apply this approach to a prosthetic arm.

Goldfarb’s power source is about the size of a pencil and contains a special catalyst that causes hydrogen peroxide to burn and produce pure steam.

The steam is used to open and close a series of valves. The valves are connected to the spring-loaded joints of the prosthesis by belts made of a special monofilament. A small canister of hydrogen peroxide that fits in the upper arm can provide energy to power the device for 18 hours of normal activity. The steam generated by the device is heated to 450 degrees Fahrenheit by the hydrogen peroxide reaction, so a concern about the device was the need to protect the wearer and others nearby from the heat. Researchers covered the hottest part with special insulating plastic that reduces the surface temperature.Hot steam exhaust is vented through a porous cover, where it condenses and turns into water droplets.

“The amount of water produced is about the same as a person would normally sweat from their arm on a warm day,” Goldfarb says.

“DARPA has set a goal of developing a commercially available arm in two years,” Goldfarb adds. “Because of our novel power source, the process of proving that our design is safe and getting regulatory approval for its use will probably take longer than that.” If DARPA decides it cannot continue supporting the arm’s development for this reason, Goldfarb says he is confident he can get alternative funding.