The day of the Virginia Tech shootings, I realized that the weather was gorgeous in Nashville– almost as gorgeous as it was on Sept. 11, 2001, in Washington, D.C.

There’s something sick in the fact that I made that comparison.Why couldn’t I just focus on the thing in front of me and say, “This is sad, this is awful, this is a tragedy”? Somehow, I became this sort of meteorological soothsayer weighing one against the other.

I don’t think I’m the only one wrapped up in comparisons, though.We end up playing this surreal game of metric relativism with history all the time.Who suffered more, them or us? Which is worse, this or that? It’s like we’re arguing macabre baseball statistics.

In the days after the Tech massacre, I allowed myself to focus on the sheer amount of information before me, amassing all the facts and details so I didn’t have to think about them too much. People I knew tended to dwell on the numbers rather than the stories, or rail against society for the failures of the university rather than face just how ubiquitous student shootings are.

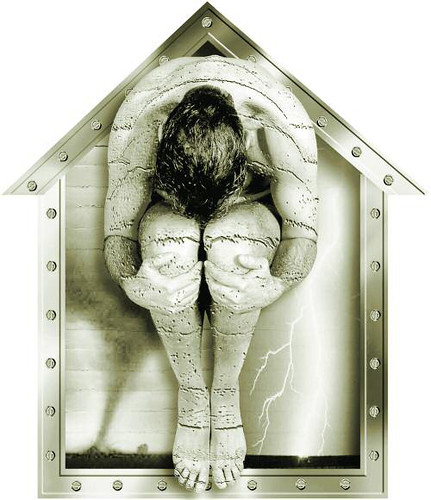

For me, though, that behavior goes beyond the Virginia Tech tragedy.Whether it’s my paradigm or a reaction to the times, I tend to shield myself from becoming emotionally invested in the issues of the day. I hate writing about serious things. I’m more at ease with obscure pop-culture references and dirty puns about well-regarded historical figures. As a generation, though, I think we’ve learned to compartmentalize and make such incidents impersonal because we know another tragedy lurks around the nearest corner.

Our parents grew up with lingering dread of the Cold War and a dismal parade of assassination and war. From Vietnam to JFK, MLK, RFK– the letters run together. Fears change, however, and our tragedies are different.

Virginia Tech was personal for me, though. I grew up in McLean, Va., and I know a lot of people who go to Virginia Tech–probably more than 50. I’m only good friends with half a dozen or so. I only know 0.2 percent of the Tech undergrad population. After the shootings they were all healthy and safe and alive. But they all knew people who weren’t. Caitlin,who’s known as an unflinchingly sweet girl, sat in lockdown for two hours in French class in a building connected to Norris Hall and heard the gunshots.

Heidi–roommate of my friends Abby and Ryan–was shot in the leg.

Adrienne, the elementary school friend with whom I worshiped at the altar of 11- year-old cool–a Backstreet Boys concert– planned on going to the University of Virginia together with her cousin Reema. They’d wanted to go to school together for a long time, apparently. Adrienne got in.Her cousin did not and went to Virginia Tech instead. On April 16, Reema was shot and killed in French class.

The boyfriend of that girl I never really liked, the one who always talked about the Yankees on the bus during our freshman year of high school–he died, too.

I feel detached from those people, though, like I’m looking at them through some sort of really thick veil. Maybe this is a kind of Facebook curse: The more information out there, and the more quickly it’s available about people you barely know and never see, the farther removed you are from them. Or maybe if the tragedy weren’t so random, if the shooter weren’t frozen in time in that one photo, draped in black, arms outstretched, guns brandished, I’d feel differently.He didn’t even know any of them. But what if he had? It wouldn’t really change anything. The 33 victims would still be 33 victims.

Our parents live with the paralyzing fear of getting the horrible call those 33 families received that Monday morning in April. This is not the first fear their generation has faced, however. They grew up with the lingering dread of the Cold War and a dark, dismal parade of assassination and war. From Vietnam to JFK,MLK, RFK–the letters begin to run together. How do you aspire to anything when the heroes are falling down? They did, though, and they achieved a lot. They faced tragedy, too, and we shouldn’t forget that.

Fears change, however, and our tragedies are different.We saw Oklahoma City at age 7, Columbine at 11, Sept. 11 at 13, the Beltway sniper at 14,Katrina at 17.We saw bombings in Kenya, London and Madrid.We saw the tsunami.We have grown up with the idea that it could be us.We’re not desensitized to tragedy–at least I don’t think we are– but we’re not surprised, either.

The moment I knew my friends were fine, I knew that someone else was finding out theirs weren’t, someone’s parents were finding out that their child was not coming home. How many more of these days will we see? How many more of us will die? Why us?

Those who died weren’t perfect; they were just like us. They went to classes and parties. They had career goals and doubts. They had people who loved, liked and hated them. They succeeded and they failed, and they probably didn’t want to go to class that morning. They were us. That was the real horror in the Virginia Tech massacre.We’re not perfect, but we didn’t deserve this.Nobody does, and yet we’re not surprised anymore.

Our generation seems to bear the burden of knowing the unthinkable will happen. Towers, cities, and that sense of security we have will fall at times. Perhaps, though, that idea is also a grace for us.We face impossible issues and problems, but if we’ve learned anything, it’s that the impossible can become reality.We can make the good kind of impossible happen, and when the bad kind jumps out and steals our favorite purse, we’ve seen that we can survive that, too.

I don’t think tragedies like these can be left aside; we need to be stronger, better and kinder after something like the Virginia Tech massacre because we have to make that day mean something. The fallen deserve better; their families deserve better;we deserve better.We must stick together, adapt, and make sure this never happens again.We’re entrenched in the most serious game of Red Rover ever played.

In the end, though, this life is what we have together–with our friends and our families. It’s not grand gestures that keep us together; it’s the everyday. Small acts of kindness and simple words of gratitude can change a lot.We don’t have to be valiant heroes or saints. Just facing and struggling with our weaknesses are enough, to me anyway. We’re not all the same, but that can make us stronger if we let it. We share a country, a past, and–I hope–a future together.

At the time of the Virginia Tech tragedy, many people, including myself, repeated over and over again that we were all Hokies and would be for a long time.Now, though,Virginia Tech seems to have slipped from our collective consciousness. The tragedy itself is incomparable, but to forget it, to gloss over our fears and our parents’ fears, to simply wait for the next April 16, would be an even greater tragedy.