In the City, you don’t stargaze. You don’t dig through wildflower field guides for the name of that brilliant trumpet burst of blue you saw on your morning walk. You don’t hunt for animal tracks in the snow or pause in that same frozen forest, eyes closed, listening for the chirp of a foraging nuthatch. You forget such a creature as a snake even exists. It’s as if New York is encased in a big plastic bubble, where humans sit atop the food chain armed with credit cards and Zagat guides. Native wildlife? Cockroaches, pigeons, rats. Disease transmitters. Boat payments for exterminators.

Our story begins in the bubble.

The year is 2000, the dawn of a new millennium. The Y2K scare is barely behind us. Economic good times lie ahead, with unemployment at an all-time low, the U.S. government boasting record surpluses, and the NASDAQ, which raised a lusty cheer by topping 5,000, making everyone rich. At least on paper. Living in the wealthiest city in the wealthiest nation at the wealthiest moment in history, Heather and I should be happy. We aren’t.

Burned Out

Like everyone we know in New York, we work too much. Job stress follows us home at night, stalks us on weekends. Heather’s work at a justice-reform think tank and mine hustling freelance magazine assignments keep each of us either chained to PCs or traveling. Within the past two years, Heather has flown to every continent but Australia and Antarctica to interview cops and meet with government officials. When she was seven months pregnant, she gave a talk in Ireland, flew back to New York, and left the same day for Argentina and an entirely different hemisphere. We figured that if she happened to give birth prematurely, it was a coin toss whether we’d have a summer or winter baby.

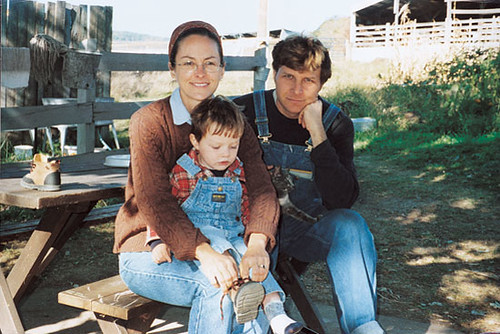

As it turned out, Luther was born more or less on time in Manhattan, in a hospital towering over the East River. By the tender age of 4 months, he was already in the care of a nanny, leaving us feeling guilty for having to hire her and also guilty about how little we could afford to pay her. (We felt guiltier still upon learning from another mother that our nanny was locking Luther in his stroller so she could gab at the park. We fired her and put Luther in day care.)

We spend too much money on housing and not enough time outdoors. We order dinner from a revolving drawerful of ethnic takeout menus and rent disappointing movies from a corner shop where the owner hides behind bulletproof glass. There’s something missing from our lives–from our relationship–and yet we’re too busy to confront the problem. At least that’s our excuse. So the two of us plod through our days hardly talking. And at night we collapse into bed, kept awake by the sound of squeaking bedsprings in the apartment above but too exhausted for any bed-squeaking ourselves.

It isn’t a physical exhaustion. The beneficiaries of a multigenerational pursuit of the American dream, we have traded the farm and factory work of our small Southern hometowns for education and urban living. Instead of a limb lost in some mercilessly churning assembly-line machine, we suffer the stress-related ills of our times: anxiety, depression, e-mail addiction, debt.

My tipping point came the day my beige plastic Dell tower–the tool of my trade–whined to a halt. The screen went black. With mounting panic, I punched the keys and poked the on/off button on the front. Nothing. Fingers followed the dusty power cord from wall socket to box. Plugged tight. My mind reeled at the thought of all that accumulated data trapped inside the wiry guts of a machine that I so little understood: pages of research, interview transcripts, an almost-finished article due three days earlier, book ideas, addresses, e-mail correspondence with friends and editors, family photos, business records, tax records. That computer was everything to me. And like a fool, I had not bothered to back it up.

Once I recovered from my initial panic, I thought back to my grandfather, a country doctor and cattle farmer. He was born in 1886, before all this so-called time-saving technology–cell phones that tie people to their jobs 24/7 and computers that keep them answering e-mails past midnight. Could someone whose tools were hand-shaped from iron, steel and wood ever grasp the ethereal nature of lithium-ion-powered digital devices? This was my dad’s dad–a mere generation stands between us–and yet he came of age in a world completely different from the one I know.

It dawned on me that no one yet understands the long-term side effects of Modern Life. Can we really adapt to all this brain-scorching change–the technological advances, the teeming cities, the breakneck pace of daily life, the disappearance of the human hand from the things we buy and the food we eat? Maybe my ambivalence about technology (and dread over my failed computer) was not something to be ashamed of. It was as if something in me shouted, Hold on a minute! You’ve been staring at the computer screen too long. When was the last time you dug in the dirt or tromped around a field, not to mention had anything at all to do with producing the food you eat? Maybe our disconnect with the natural world causes a sort of vertigo, and if so, maybe that explained my recent unhappiness. Or maybe I was just pissed off things weren’t going my way. Whatever the reason, on that day I dreamed of escape.

And yet I dutifully called a Dell technician. With a wife and child, and a career to pursue, what choice did I have?

A few weeks later I had a moment of clarity that in a flash changed everything. I was reading a newspaper story about an upcoming PBS show that pitted an English family against the rigors of 1900-era London life. Thinking back to my computer crisis and the question still ringing in my mind–What choice did I have?–I realized I had found my answer! Not the reality show itself, but rather its core concept–adopting the technology of the past. If I were so desperate for a change, why not travel backwards in time as a way of starting over?

The year 1900 immediately felt right. I wanted to ditch certain technologies, but I did not want to be a pioneer, having to build a log cabin or dig a well by hand. The year 1900–almost within memory’s reach–would serve well. A bit of research bore out my intuition. In 1900 rural dwellers still outnumbered urban dwellers. In 1900 agriculture was still the predominant occupation, thanks to millions of small-plot American farmers who raised most of what they ate for breakfast, lunch and dinner. In 1900 the motorized car was still a novelty. In rural America there were no televisions, telephones or, of course, personal computers. People still wrote letters by hand. And this was crucial: In 1900 you could buy toilet paper.

I nervously told Heather my idea one Saturday as we juggled our fussy baby in a cramped Brooklyn pub. She smiled, and I remembered why I fell in love with her.

Old Year’s Eve

After selling our apartment and cutting ties with New York, we begin laying out the practical steps necessary to recreate 1900 and live there for a year. We find a 40-acre farm in the Shenandoah Valley community of Swoope, Va., with an 1885 brick farmhouse fronted by a sweet little porch with scrollsaw pickets.

We begin chipping away at our to-do lists: make house livable and period appropriate, dig privy hole, install manual well pump, stock up on old tools, hammer up animal stalls, convert waist-high tangle of weeds into vegetable garden.

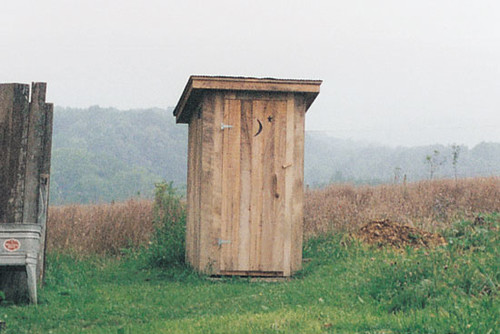

By spring 2001, a pair of milk goats nibble grass in the barnyard. Half a dozen chickens scratch around the henhouse with southern exposure. Looming over it is our 100-year-old barn. The outhouse stands atop a freshly dug hole.

In between the sledgehammer and the crowbar work, the wallpaper scraping, the digging, the hacking and hoeing, we begin hitting the books, digesting generations’ worth of farming lessons in the equivalent of a college semester: Do store carrots in layers of damp sand and apples in a box. Don’t store them side by side or the carrots will taste bitter. Don’t cellar pumpkins because they’ll rot. Do put pumpkins in the attic, but don’t let them freeze. The best laying hens, we now know, have moist rectums, though how to use such advice remains a mystery.

Since we have no trees, I pay a guy with a “Don’t Make Me Open This [Can of Whoop Ass]!” bumper sticker on his pickup truck to supply enough unsplit rounds of firewood for about 13 cords.

In place of our Taurus wagon, with its missing hubcap and 174,000 miles, we have Belle, a 2,000-pound Percheron draft horse. We stash the telephone in a drawer after canceling credit cards, car insurance, Internet account.

A guy from the power company knocks on the door. “Says here you put in an order to cut power,” he says, sounding confused.

“That’s right,” I say cheerfully.

“You want me to cut the power off?” he repeats, looking past me at a kitchen filled with food, furniture, and other signs of habitation.

“Yep. Cut it off.”

We are almost there. Soon the darkness will fall.

In the Dark

It only takes a couple of days of morning headaches and unintended brunches to realize that if we want breakfast at a decent hour, one of us–me–will have to get up early to start the cooking fire. That means waking before sunrise. Unless the moon lights my way, I am blind for as long as it takes me to strike a match–if I remembered the night before to stash the matches on the nightstand.

On Day Four, I rise in a room as dark as death. No matches. Feeling around for my shorts and T-shirt, I whisper curses, hoping I don’t rouse Heather or, in the adjacent room, Luther, who has been waking up at night screaming for a nightlight. I feel my way out of the room–easy now, slow and easy–hands caressing cool plaster along the wall to the stair landing’s low walnut railing (it hits me just above the knees). I follow my feet slowly down, down, praying Luther did not leave a wooden train car or stuffed bear on the steps. I continue, around the newel post and into the creaking hallway, around the corner and–oof!–I bump the ceiling where it slants to meet the stairs. Easing through the doorway into the sparsely furnished living room, I can feel the age of the house, my fingers rippling over the wide, hand-planed jamb.

In the kitchen I smell onions and curry, hear the cranch, cranch of scraping mice teeth. Our rodent problem started as soon as I began chasing away the black snakes. We find nibbled corners on our cheese, little turds on the kitchen table, hear scuffling claws above us in the ceilings. Where are the matches? I want to reach for a light switch. Or feel the reassuring click of a flashlight button beneath my thumb. Instead, I shuffle my feet, letting the vermin know I’m here, while feeling around for the box of kitchen matches. I stick my hands into baskets and cobwebby crannies, feeling for a rectangular box with an emery strip. My blind arms tip cups and bottles. I brush something off the shelf above the stove. It crashes to the floor with a tinny sound that I instantly recognize as made by one of our oil lamps. I stoop and carefully feel for broken glass. It is whole. When I find a box in the washroom cabinet, I return to the stove where I righted the lamp and strike a match. The darkness melts.

That night, before bed, I walk through the house like a pyromaniac Easter Bunny, hiding matchboxes on shelves and in dressers in as many rooms as possible, hoping Luther will not find them.

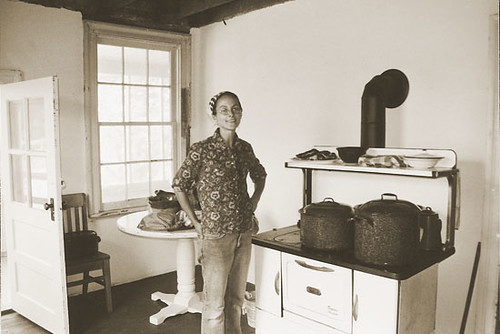

In more than one way, we feel our way along during these early days. Everything is trial and error, from pinning cloth diapers on Luther to battling the green worms devouring our cabbage plants. I learn to feed a new log into the firebox every 15 or 20 minutes to keep it heating consistently. Heather learns to cook all meals in the morning, letting the fire die before the sun beats down with full intensity. We’ve stocked up on the dry goods the typical 1900 family would have been able to buy at a general store–coffee, tea, sugar, oatmeal, rice, soap, baking powder, among other things. And we’ve bought extra, since there is no longer a general store where we can replenish our supply. Using a collection of misfit cookware–cast-iron pots and skillets, chipped enamelware saucepans–Heather makes oatmeal, skillet toast or fried eggs for breakfast. She boils rice, simmers dried lentils or kidney beans, steams collard greens or broccoli from the garden, and bakes cornbread, covering everything and leaving it on the warming shelf until lunch. Dinner is cold leftovers. We drink well water, ladling it from a crock that stands on a table in the kitchen.

Headbutt

“They’re nice goats,” I say, putting down the buckets. “They won’t hurt you. See?” I crouch and put my arm around Luther’s shoulder while petting Sweet Pea’s smooth tan coat. They are nice goats, less menacing than most dogs, even though Star, the big black one, did playfully lunge at Luther the day after we brought her home. I didn’t think much of it–didn’t have the time, really–and since then have been trying to abate Luther’s fears. He’ll just have to grow comfortable with the animals. It will be good for him. “Up, up,” he whines. I ignore him, turning to unlatch the barn door. Suddenly, out of the corner of my eye, I see Star rear up on her hind legs. In half a breath, she cocks her head to one side and thrusts her body forward. Her bony skull meets Luther’s squarely in the forehead with a blow powerful enough to launch him through the air. He lands with a bounce on the rocky ground.

“STAR!” I yell, kicking her hard and running to Luther. His face is scrunched up and red. A scream swells in his lungs and finally bursts from his lips. I scoop him up into my arms and, crazy with rage, chase the goat, kicking at her while hugging Luther to my chest. Coming to my senses, I stop and run to Heather, who now stands at the garden gate. “Star butted him!” I say, handing Luther to her over the gate. No blood, no broken bones. “Why did you put him down in there if she butted him before?” says Heather, scowling at me. Then she changes her tone, soothing Luther with soft words while rocking side to side. He keeps screaming.

“I don’t know!” I say, breathless. “I can’t believe she really did it.”

I sprint after Star, trying to kick her again, swinging my leg so hard I throw my body out from under myself. I hit the gravel with a lung-crushing thud and roll. She runs to the back side of the barn. I follow in a fast-moving linebacker’s crouch. She’s bleating her head off, tongue wagging in cartoon desperation. I move like an animal. She tries to race past me, but I grab her stubby tail and catch hold of her collar, shoving her into her stall.

Sucking air into my lungs, I go to find Heather and Luther.

They are sitting at the picnic table in the shade of the silver maple, Luther calm now but still in Heather’s arms.

“Star butt Luther,” Luther says in a pouty voice. “Daddy give Star timeout.”

“I sure did,” I say, making the words sound upbeat, “a loooong timeout.” But inside I feel horrible–for letting it happen and for losing my temper afterwards. It must be my exhaustion, I tell myself. I can hardly face Heather. I turn and walk back towards the barn. The goats need water, and so does Belle. I need lunch, but that will have to wait.

Bad Pop Songs

In New York we had music on all the time. Latin dance music, Brazilian Bossa Nova, REM, Mahler, Miles Davis. But now, with our supply of music cut off, I am a prisoner to every stray tune that pops into my head. Some are personal favorites. Most seem to have been sent only to torment me.

The first tune that sticks is “Red, Red Wine” by UB40. It pops into my head one day while I am cultivating beans, and it stays there for days. I’ve never liked the song, but something about its simple melody and reggae beat keeps it glued there, the rap-like chorus looping: “Red, red wine, you make me feel so fine/You keep me rocking all of the time.” I can’t remember any other lyrics, so I invent words to go along: “Red, red wine I want to hold on to you/Hold on to you until my face turns blue.” And so on. “The line broke, the monkey got choked/Bah bah ba-ba-ba bah ba-ba ba-ba. Yeeaah.”

I hum “Red, Red Wine” while hoeing, mouth “Red, Red Wine” under my breath as I kneel to pull weeds, clamp my lips together to keep “Red, Red Wine” from spewing out, and then hear it sloshing around my skull. “Red, red wine make me feel so … .” Shut UP! I’m worse than the mumbling crazies we left behind in New York. I try to stop the torture by pretending to end the song, playing it out with an overly dramatic “bum-BAH.” But it comes back like the flame on one of those trick birthday candles. The only solution is to swap it for a better song. “Blackbird singing in the dead of night,” I sing through gritted teeth, holding the tune up like a crucifix. I work my way through as much of the Beatles’ White Album as I can remember, using “Blackbird” and “Mother Nature’s Son” to part the sea of “Red, Red Wine.”

But freedom is short lived. Other random tunes creep in to fill the void: Aerosmith’s “Walk This Way”–the rap version. The Go-Go’s’ “We Got the Beat.” It’s maddening. Here we are trying to faithfully recreate the year 1900, and while splitting wood or pumping water I wah-wah the theme music to Sanford and Son or thump out the bass line from Barney Miller.

Curiously, most of what sticks is from my childhood–sitcom themes, commercial jingles, songs by the Bee Gees, the Commodores, and KC and the Sunshine Band. It’s not period-appropriate in the least. If our story had a soundtrack, it wouldn’t be some Ken Burns-style collection of haunting mandolin melodies. It would groove, baby. Do a little dance, make a little love, get down tonight!

News from the Future

I am sitting on the screen porch shucking corn, with Luther at my feet tugging at the husks, tossing hairy, half-shucked ears in with my clean ones.

An engine growls up the driveway, and a Jeep Cherokee skids to a stop. It belongs to Wesley and Crystal Truxell, who live nearby.

“Have y’all heard?” Wesley says.

“It’s all over the TV,” Crystal says. “Terrorists are flying planes into the World Trade Center.”

“Man, they’re everywhere,” Wesley interrupts, words tumbling out. “They blew up the Pentagon. There’s a plane down in Pittsburgh. This is big time.”

Within 20 minutes, three cars line the driveway and we’re huddling with our neighbors, trying to fathom events possible only in a nightmare.

I think of my brother and his wife, and of our friends David and Meryl, who both work within a few blocks of the World Trade Center.

“I bet this will make you want to watch television,” says Wesley.

Yes. No. Hell, I don’t know what I think. This is all so strange.

“Come on down and use our phone,” he says. “You don’t really care about your little project enough to not call, do you?”

All day long I wonder if maybe Wesley’s right. In the shadow of such enormity, the whole project suddenly feels little. Don’t we have a responsibility to our families and friends?

Are we turning our backs on our own era during a time of need?

Here, we can only imagine what the rest of the country is going through. We can only live our lives. Which we do, with the same regularity as before, going through the motions feeling empty and strange. The peacefulness of the farm seems pregnant with irony. How can New York be reeling from death and fiery destruction, when here all is innocence and calm–chickens clucking in their nests, cats trailing me for milk as I clink down the path with a frothy pail, Luther jabbing a spade in the dirt?

At night we try to write letters but the words fall flat, and we give up. Instead, we sit opposite one another on the chilly side porch, sipping bourbon and taking turns reading Pride and Prejudice aloud to one another.

I’m not sure whether it is resignation or faith, but something helps me abide. I get by without the crutch of technology, the false sense that minute-by-minute news coverage or phone contact puts us in control. I have never been a very patient person. And yet something in me has changed. Over the past few months, I have been calmed by the lack of 21st-century distractions and humbled by the power of nature. Like the weather, the terrorist attacks were beyond my control. All I can do is cling to the simple assurance of daily chores.

We are relieved to learn from letters that my brother and his wife and David and Meryl are fine. Other mail from New York trickles in. Any time we see a New York postmark on a letter, we open it slowly, not sure of what we’ll find inside. We read harrowing details from friends about the smell of burned flesh and the greasy ash that fell like snow.

FRUITS OF LABOR

Winter marches at us. A few cold nights in September stunned the summer garden. A hard frost in early October knocked it out for good, sending a rich smell rising from the blackened plants like a final breath. We surpassed our goal by preserving more than 350 jars of food, including corn, squash, okra, pickled cucumbers, dill-seasoned pickled green beans, and more than 100 quarts each of tomatoes and green beans. We made three dozen jars of blackberry jelly, put up 14 gallons of apple cider, dumped a bushel and a half of potatoes in the bins, stored pumpkins and winter squash and onions. We put up a half gallon each of dried lima beans and field peas.

As the neighbors bring news of war in Afghanistan and anthrax scares, I realize how lucky we are to be together on these peaceful 40 acres. Not only do we now cook, clean, split wood and tend the animals with brisk efficiency, but the pressures of summer have eased. We return from the cellar lugging a basket brimming with food and a half gallon of apple cider, all of it put up by us, feeling proud and secure.

For the first time since my boyhood, I offer silent prayers of thanks without getting hung up on the theological details.

Old-Fashioned Rooster-Killing

“Would you help my friend Dot Makely slaughter some roosters?” asks Liz Cross. “She’ll give you one for every three you kill.”

Liz, who lives with her husband, Jack, on a few acres nearby, stands like a farmer, leaning back, hands stuffed in pockets. In the middle of her sentence, she shifts her weight slightly and farts, clearly but not loudly, with no blushing or begging of my pardon or comments about frogs, as if passing gas during a neighborly chat is the most natural thing in the world, which, arguably, it is. “Dot’s blind,” she says. “Well, mostly blind.”

I visit Dot Makely’s during the day, pedaling over one afternoon with a pair of canvas gloves in the basket and a nervous stomach. A big, boyish man, probably 40, wearing a grimy mechanic’s uniform, answers the door, scowling. I realize I’m dirty, too, and wild of hair. “Is Mrs. Makely here?” I ask. “I’m your neighbor. I came about the roosters.”

“Mommm!” he calls, turning and shuffling into the cramped house. I follow. He points at a woman sitting at the kitchen table and then plods into an adjoining room. I hear television voices and laughter and see blue flashes, like dull, boomless fireworks, lighting up the dark room.

“Liz Cross said you needed some help,” I say, introducing myself. Unlike her son, Dot Makely is perfectly charming, launching into conversation as if we were old friends and had been sitting over lunch since noon. We talk. Actually, she talks, and I listen. She talks about her chickens and the coyotes that come down from the mountains to stalk them; about her land, which she kept after she and her husband divorced; about her spring, which is still flowing despite the drought. It’s as if her mouth, rather than her ears or nose, has compensated for her blindness. Which is fine with me, since the talking postpones the killing. All I can think of are the neck-wringing stories I’ve heard. Now that I have chickens–and know how big they get–I can’t imagine ripping the head off one.

“Listen to me, gabbing on and on,” she says. “You’ve probably got things to do. Let’s go find those roosters!”

Like a debutante, she takes my arm, and I lead her slowly outside. She’s a tiny woman and spunky, despite her age and her lack of sight, with a bright, smiling face. I guide her around a bunch of ankle-twisting walnuts scattered on the ground.

“I was so fond of walnut trees when I was a girl,” she says. “I asked my mother once, I said, ‘Mother, will there be walnut trees in heaven?’ She said, ‘No.’ I told her, ‘Then I don’t want to go.'”

A fowl flutters past with a startled cluck.

“Is that a rooster?” Dot asks.

“I have to admit my ignorance,” I say. “I can’t tell the difference.”

I’m only here because of what I call our “country cred,” which is like street cred, only different. Because we are living off the land, people assume we know more than we do about country life. Not even Liz Cross cooks on a woodstove or drives a horse and buggy, and Liz can do anything–including strip down a car engine to a pile of nuts and bolts and parts and piece it back together (which I know because Jack Cross told me so while wearing a look of pure husbandly pride on his face). But even though I’ve learned some 1900 skills, I still have a hole a mile wide in my country-living résumé. No matter. Liz still comes to me to kill the roosters for the blind woman.

“Oh, the roosters have bigger combs on their heads,” Dot says, matter-of-factly.

“And they’re a lot more aggressive.”

We enter the henhouse, where 20 birds of all sizes, shapes and colors explode in a panicked cackling, beating up a toxic, lung-choking dust.

“Be careful,” she says. “They can be mean.”

Gloves on, I chase what looks like a rooster into a corner, yanking its legs out from under it before it can peck my eyeballs out. I carry it upside down, holding it well out of range of anything it might target below my waist. We walk back up the hill, where an axe leans against a stump.

“Just chop the neck,” she says, holding the bird’s head. “And try not to cut off my hand.” Gripping the legs in my left hand and the axe with my right, I try to concentrate, but Dot won’t stop talking.

“Roosters flop around so much after you cut their heads off,” she says. “Drop it quick. Otherwise, you’ll get blood all over you.”

I raise the axe, arm wavering under its weight.

“I hope people don’t do that,” she says.

“Do what?” I say, lowering the axe.

“Flop around when you kill them. It would be horrible–in a war or something. You’d see bodies flopping around.”

“I’m pretty sure they don’t,” I say, raising the axe. I lower it again when I realize she’s not finished.

“I hate war. The one we’re in has me so angry,” she says, referring to the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan, now about a month old, which we know because the neighbors have kept us informed. “I can’t really say anything, though, since I don’t vote.”

“Why not?”

“I’m a Jehovah’s Witness. We don’t believe in it.” Determined to finish the job, I stop asking questions. Soon the conversation peters out.

“Here goes,” I say, raising the axe again. The bird, still stretched across the stump, wriggles pitifully. I let the heavy iron head fall. It bounces, as though I’ve just hit a rubber hose. The rooster’s eyes bulge. I raise the axe again. Thud. The head tumbles.

Stepping back, I drop the rooster and the axe, the blade barely missing my foot. The rooster hops away, shaking out its wings in a gesture of freedom as blood spurts from its neck. But then, as if suddenly realizing that something is terribly, irrevocably wrong, the bird panics, flapping and flopping in a silent scream. Spraying blood, it somersaults down the hill, regains its feet, tries to fly. Blind–worse than blind–the bird smacks into a tree and pinballs off in another direction. It hops. It spins. My god! I think. Will it never end?

But it does, and we go after more roosters. The second one flops, just like the first. I don’t drop the third bird quickly enough, and blood spatters my cheek and pants and boots. Dot is effusive in her thanks, and it’s all I can do to convince her that I don’t need a dead rooster for my services.

Home for the Holidays

With my folks coming for Thanksgiving and Heather’s for Christmas, this holiday season will be our chance to give them a glimpse of our life in 1900.

The typical farm wife 100 years ago couldn’t choose convenience over made-from-scratch. Neither can Heather. At times she’ll stand outside the henhouse tapping her fingers, waiting for an egg to round out a recipe. (Once, while making brownies, she impatiently reached under a hen and was sharply pecked.) Using our limited ingredients, Heather has adapted to the challenge of cooking three meals a day, seven days a week, with energy and creativity. We have never eaten better in our lives.

On Thanksgiving the sight is enough to make everyone–my parents, my brother and his wife, who have joined us from Brooklyn, and our neighbors Peggy and Bill Roberson–gasp. Food rests on every kitchen surface: steaming bowls of corn pudding, roasted potatoes flecked with rosemary, green beans, and rice and gravy; pans of moist cornbread dressing seasoned with sage that Heather planted, harvested, and strung up to dry; pickles, deviled eggs, the Robersons’ cranberry salad and candied yams; Heather’s yeast rolls, including a couple of misshapen ones kneaded by Luther; her two pumpkin pies; and a platter of sliced turkey, which cooked to perfection in the intensely hot, slightly smoky box, the heat searing in the juices and Heather’s seasoning.

“I had no idea the food would be this good,” my mother admits, as we rock on the front porch (there being no televised football game to keep us inside). But it’s not just the food. It’s the lack of hurry and distraction. We have lingered over meals, pressed apple cider, and visited with the neighbors. My mother has taken walks along the gravel road, pulling Luther in his wagon. An artist, she has been sketching the cows, barn and mountains.

A couple of days later, we say our goodbyes in the driveway. After hugging Luther, my mother turns to me. “You and Heather have created a wonderful life for yourselves here.” I no longer fear silence. The bad pop songs in my head are gone. That, along with the lack of technological distractions, leaves me available both physically and mentally to witness nature’s wonders: the nightly march of the stars, muskrats gliding for great stretches beneath the river’s frozen surface, the misty-morning revelation of spiderwebs by the hundreds, glistening like spiral galaxies in the meadow grass.

I am amazed at my sturdy, competent hands and marvel at my patience and drive, a reversal from the run-down edginess that dominated my moods in New York.

Mornings have become my reading time. Once I’ve built fires in both the heating stove and the cookstove, I’ll huddle close to the kitchen stove listening to the crackle, soaking up the heat and reading a book. My new powers of concentration astound me: I’ve raced through Dickens, Hardy, Wilde, Hawthorne, Irving, William Dean Howells, the collected letters of Thomas Jefferson, and several novels published in 1900.

Preparing for Re-entry

Even though our project is not driven by nostalgia, we find ourselves growing nostalgic for our 1900 experience even before it comes to an end. One day, after we put Luther down for his nap and finish our chores, we tiptoe up to the guest room and sneak under the covers. Afterwards, we are silent, and I sense an unspoken understanding between us that soon this, too, will change. I’ll get busy again with work, the phone will ring, we’ll spend too much time in the car driving to and from town.

And then there’s the nagging reality of how we’ll support ourselves. Simmering on the back burner all this time was our idea of starting an artisanal goat-cheese farm. We have the land and the barn. With some train-ing–perhaps a few sabbaticals to France–we could build on Heather’s already considerable cheese-making skills. It would be perfect: We’d use what we learned in 1900 to build a new life once we returned to the 21st century.

But there are two problems.

They come to light one evening at dinner, when I offer Heather the last slice of an olive-oil-drizzled chevre that I have pretty much devoured.

“You can have the cheese,” she says, an odd smile on her face.

“What’s that supposed to mean?” I say.

“I can’t eat it.”

“You can’t eat it? It’s delicious.”

“I can’t stand it any more. I stopped eating goat cheese a couple of months ago. I stopped drinking the milk, too.”

I’m dumbfounded. “I never noticed.”

“I kept making it for your sake,” she confesses. “I didn’t want you to find out. I thought you’d be disappointed.”

“About our farm idea?”

“Yeah.”

I burst out laughing.

“What’s so funny?” she says.

“I’ve got a confession, too,” I say. “You don’t like the cheese. I can’t stand the goats!”

Back to the Future

What do we do on our last day? Sleep late, take the day off, celebrate? No. We milk, pump, cook, clean, whack weeds, shovel manure, and mulch the garden paths. We also prepare for re-entry. John Foster drops by and helps me remove the animal nests from the Taurus and splice the chewed wires. We pull enough straw out of the engine to stuff a mattress. He takes the battery and brings it back fully charged. Even though we’re not going anywhere–until tomorrow–I can’t resist sitting in the driver’s seat and giving the key a try. She sputters and starts up. I let the engine run for a while, and then I shut it off and pocket the key.

At the end of the afternoon, Heather throws up her arms in a gesture of triumph. “Wooohoo!” she yells. “I did everything on my to-do list today. I think that’s a first.”

That evening at dinner, in addition to rice and beans, we fulfill my vow to eat fresh English peas before the project’s end. We only share a few forkfuls between us, a meager harvest, I know. But at least we’ve done it! We planted, cultivated and picked these peas–the first yield in this year’s long growing season–so that they may now nurture us. If I take away anything from our 1900 experience, it is a newfound appreciation for the miracle of the seed. Heather and I have proven that a rubber-band-bound clump of seed-filled envelopes can feed a family of three for a year. And also that an idea–no matter how quixotic–when tucked into the fertile folds of imagination, can grow into a complex and miraculous thing.

Later, both of us are on hand to kiss Luther goodnight. We smile down at him and hint at the excitement that awaits us the next morning. Though he doesn’t understand the significance, to us this night feels magical, like Christmas Eve.

“I had the craziest dream last night,”

Heather says, as we brush our teeth out back, beneath the maple tree. “I dreamed it was our last day. I decided to plug in the phone early. What’s a day? I thought. I’ll just make sure it works. But then it rang, and I panicked.”

“Did you answer it?” I ask.

“Yeah. The voice on the other end said, ‘Gotcha!'”

“Creepy.”

We climb into bed, dreaming of all we’ll do. Basking in our accomplishment, feeling secure at having found a home, we’re not worried right now about the future. We have money in the bank for renovations, though less than we had hoped. More important, we have each other. The future will fall into place.

Heather turns to me. “See you in a hundred years,” she says, and blows out the lamp.

Since re-entering the 21st century in 2002, the Wards have lived in Staunton, Va.